Debunking the Syrian State Narrative of “Abandoned” ISIS Camp in al-Hol

People walking out of al-Hol after the camp’s security fence was torn down amid chaos inside and around the camp on 20 January 2026. | Picture Credits: X

On Tuesday, 20 January 2026, viral social media videos depicted uncontrolled mass escapes from the sprawling al-Hol camp in Syria. That day, its gates lay wide open as the result of a major security vacuum created amid the Syrian Transition Government (STG) forces’ blitzkrieg advance in the region.

The camp’s main section held roughly 17,500 people from Iraq and Syria, primarily Islamic State (ISIS) militants’ family members, as well as those pushed into homelessness when the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) defeated the terror organization’s territorial rule in 2019. The camp’s high-security section, known as the ‘Annex’, held an additional 6,400 foreign nationals who allegedly traveled to Syria to join ISIS.

Security experts have estimated that ISIS members were able to maintain a functional clandestine organization within the camp that exerted a degree of ideological and behavioral control over its population. Violence plagued the camp, especially in its early years, as the organization’s ‘morality police’ tried to dictate daily life according to its extremist rules. At the time, al-Hol had one of the highest murder rates per capita in the world.

Together with the outbreak of ISIS prisoners in Shaddadi on January 19, these events constitute the biggest security incident in the history of the terrorist organization. Yet, the circumstances of these incidents have been buried in the ‘fog of war’, with the SDF and the transitional government of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) blaming each other amid non-existent independent access to the facilities.

Moreover, prominent international newspapers seem to have adopted elements of the narrative pushed by ISIS, HTS, and the HTS-led Syrian Transition Government (STG). According to this narrative, the “Syrian army” found the camp “abandoned by Kurdish forces” when it arrived at the scene later to restore order.

The BBC reported that the SDF abandoned the camp, “triggering unrest that forced aid agencies to suspend operations.” France24 reported that the “Syrian army entered” the camp on January 21, a day after the SDF withdrawal.

Le Monde claimed that “unverified rumors circulated of breakouts from al-Hol camp after the Kurdish guards withdrew.“ The National quoted anonymous STG sources to report that “no one had escaped from the center.”

However, an investigation of social media footage from al-Hol on January 20 exposes significant discrepancies in this narrative. Videos and photos, verified and geo‑located by the author, contradict the causal order presented by HTS-affiliated sources, the version of events that international newspapers subsequently echoed without adequate verification.

Instead, the digital evidence suggests an opposite causality: the SDF pulled back only after unrest inside the camp had already escalated beyond control, as the imminent arrival of a STG-affiliated military convoy and armed clashes in the nearby town threatened the camp guards from outside.

January 19

On January 19, the SDF and affiliated Internal Security Forces (Asayish) were still indisputably in control of the camp. Further south, STG forces seized Shaddadi, allegedly releasing high-risk ISIS members from the town’s prison. They advanced north through the sparsely populated desert in southern Heseke governorate and by nightfall, controlled the southeastern countryside and roads leading to Heseke city, the closest major city to al-Hol.

That day, the first video depicting the mass escape from al-Hol spread on social networks. A closer inspection, however, revealed that this video depicted a counter-ISIS police operation in the camp on 5 September 2025 and was falsely attributed to current events.

No evidence was found to suggest that the camp security was compromised on January 19. However, the STG-affiliated forces’ growing dominance on roads south and west of al-Hol indicates mounting military pressure on the camp’s security forces that day.

January 20, early day (9 AM- 3 PM)

On January 20, a series of videos (first, second, third, and fourth) spread on social networks, claiming to show STG-affiliated forces controlling the roads leading to al-Hol in the morning hours. While the precise locations of these videos remain unverified, they credibly depict the sparsely populated, uneven desert terrain surrounding al-Hol and portray motorized formations large enough to prevent civilian traffic or small SDF patrols.

At the same time, a prominent ISIS-linked Facebook page, which focused on detention camp affairs, reported to its followers in al-Hol that STG forces had arrived in the vicinity of the camp. The channel urged its followers to “seize the opportunity” and break the gates of the high-security annex where foreign ISIS suspects were held.

According to the camp’s former director, Cihan Hanna, whom The Amargi interviewed for contextual insight, the Heseke-al-Hol road was cut off overnight by STG-affiliated forces.

“The checkpoints on the road were attacked and set on fire,” she said.

She said only the guards and humanitarian workers from the night shift were at the camp that day, and she stayed in constant phone contact with them. They called her “after midday” to report unrest inside the camp, and gunshots were heard in the background. Her sources said the camp headquarters and the Kurdish Red Crescent (KRC) offices were looted and burned. According to them, this took place while part of the camp guards were in al-Hol town, confronting an armed attack.

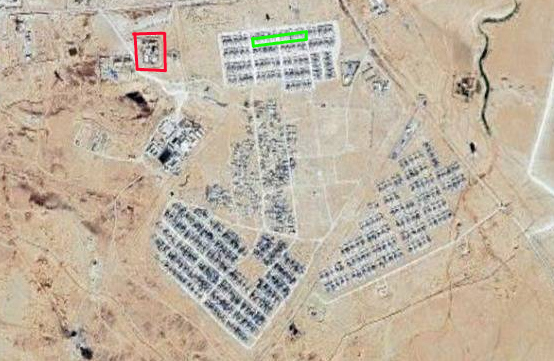

While the digital record neither proves nor contradicts Hanna’s testimony in full, several pieces of evidence lend it credibility. Later in the evening, Syrian state media SANA released a video that shows smoke rising above the camp at sunset (5:30 pm) when the STG troops had taken the camp perimeter under their control. Although the footage does not reveal when the fire began, the smoke appears to rise directly from where the camp administration and KRC offices are situated (blue in the image below). Both facilities sit right next to the camp’s main entrance (marked in red) at the eastern end of the camp’s “main street,” corresponding to the sand road shown in the video at the 00:42 mark.

Two days later, a France24 news report featured drone footage showing the camp administration offices indisputably in flames, labeling the clip as filmed on January 21. Cross-checking the footage against other videos and photos suggests that F24 may have misdated the clip. Moreover, in another report, the channel incorrectly reported the Syrian army entering al-Hol on January 21 (instead of January 20).

There is, however, one photo from which the timing of unrest inside the camp can be estimated.

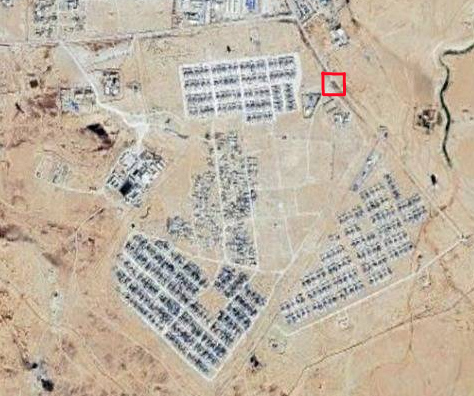

Published on the above-mentioned ISIS channel for camp affairs at 3:00 PM, January 20, the image shows smoke rising from what ISIS calls the “red prison.” The channel likely refers to the small detention center on the western side of the annex (red in image below). It is a red-brick building where people are held while investigated for suspected ISIS membership or crimes committed in the camp. The photo’s perspective aligns with the annex’s layout and places the photographer inside it (green in image below).

Furthermore, the camera’s established westward orientation reveals the shadows’ direction (to the north), allowing an estimate of when the photo was taken. Analyses with Shademap and SunEarthTools, software to determine time from the sun’s position and angle, placed it around noon, within the 12–12:30 PM window.

While the ISIS channel could have a motive to recycle an old image to sow confusion, a reverse image search produced no earlier instances of the photo, and no news was found about the building having burned before. Additionally, as the southward drifting smoke in the picture matches exactly the wind direction and speed seen in the SANA video that captured a separate fire the same day, the image appears authentic.

Finally, a video also recorded gunshot sounds inside al-Hol, although its location and time have not been verified due to its limited field of view. The author considers the video credible and likely filmed in the camp that day.

Around the same time, the first set of verified footage surfaced depicting a firefight in the town of al-Hol, roughly a kilometer north of the camp. The first video shows armed men running along a street with chants of “Allahu Akbar.” From the video, it is evident that the armed mob was trying to storm the town center. The video’s vantage point aligns with the geometry of al-Hol’s main street, one block away from the town center (36°23’18.0″ N 41°08’56.0″E), and the gunmen indeed run toward the town center from the direction of the camp. Using Shademap and SunEarthTools, the author placed the incident between 2:30 PM and 3 PM. The Rojava Information Center (RIC) has independently verified the video.

The second and third videos appear to document a firefight, filmed simultaneously from the opposing sides of the side street leading to the former government office, which served as an Internal Security Forces base. The videos’ timing is practically simultaneous with the first video from the main street. The RIC has independently verified the first video.

A fourth video, allegedly filmed in the camp’s vicinity, shows a convoy speeding down a rural road and was circulated as evidence of an SDF withdrawal. The author considers the video authentic and filmed from a rooftop (36°24’21.1″ N 41°06’41.8″E) in the nearby village of Abu Hajirat Khuatana at roughly 2:30 PM. The convoy is unmistakably military, and it is difficult to see any other actor than an SDF-affiliated force driving westbound on that road at that time. It is not clear, however, if the convoy is withdrawing from the al-Hol area altogether or maneuvering to reinforce the western flank where a motorized STG force was approaching the camp (as evidenced by the footage further below). The RIC has independently verified the video.

Taken together, publicly available digital evidence outlines a coherent sequence of events:

In the morning hours, STG-affiliated formations tightened their military control on the roads leading to al-Hol with forces large enough to suppress civilian movement or small security patrols. At the same time, ISIS alerted its followers inside the camp to launch a riot upon the arrival of STG troops.

By 1 PM, a riot was well underway: at least one (but likely three) key administrative buildings were burning, and gunfire was heard inside the camp.

By 3 PM, irregular anti-SDF formations had effectively taken over al-Hol town, and the SDF had pulled a major force from the area.

January 20, afternoon (3 – 6 PM)

The SDF announced its withdrawal at 4:10 PMon X and at 4:12 PM on its web page. Earlier, at 3:41 PM, it had reported ongoing “violent clashes” near the camp with “Damascus-affiliated factions.” In a later interview with the local Hawar News Agency, the SDF commander-in-chief Mazloum Abdi said the redeployment followed “fierce clashes involving armored vehicles and tanks.”

Social media footage confirms clashes in al-Hol, but publicly available evidence neither verifies nor disproves the involvement of armored vehicles and tanks. Armored vehicles do appear in the earlier video purportedly showing the STG column heading to al-Hol. Additional footage further shows regular STG forces reaching the camp before the SDF withdrawal announcement.

In the late afternoon, two videos (first andsecond) surfaced on social networks showing the arrival of STG troops. The author verified and geolocated both clips to the camp’s eastern security perimeter. BBC Verify, the X user @Stinky915846091, and the RIC have independently verified the video.

More precisely, the footage shows STG-affiliated troops arriving from the west and stopping their cars next to the perimeter at the western end of the main camp’s “main street” (36°22’25.1″ N 41°07’40.3″E). Their route suggests they were not local groups but coming from the direction of al-Hol oil fields (20 km west) or Heseke.

In both videos, dozens of people walk freely out of the camp. The arriving troops make no visible effort to stop them and instead appear to encourage them with “Allahu Akbar!” chants. Again, the shadow lengths and angles imply an afternoon time, and the author estimates these videos were shot around 4 PM.

A third, roughly simultaneous video depicts an armed man next to an open gate on another side of the camp. When a passing child asks, the cameraman (who cannot be identified from this material) confirms possessing a weapon, and says their cars would help the runaways flee.

The setting sun over the camp implies the video was filmed on the camp’s eastern side. The unique constellation of a checkpoint and two gates, one to the camp and one closing the road, pins the location at the eastern gate (36°22’21.4″N 41°09’10.4″E) of the high-security annex, where the most dangerous ISIS suspects are held. BBC Verify and the RIC have independently verified the video.

Later videos and photos by Syrian state media SANA portray the camp’s security perimeter already in solid STG control at sunset, even as smoke continued to rise from inside. The sunset (5:30 pm) thus marks an undisputed endpoint to the period during which solid control shifted from the SDF to the STG.

Finally, during the investigation, a widely shared video claiming to show a mass escape from al‑Hol was found to be misattributed to the events.

The built environment in the video does not match any location in al-Hol known to the author. Although the checkpoint structure (blue) resembles the camp’s western gate, no road to the camp has a median (yellow), and no other footage from the gates that day shows the second billboard or sun cover structure (red) visible farther down the road. The video also features two buildings (purple), far bigger than any in al-Hol.

On the same day, a Facebook post claimed the same video showed civilians accompanying an STG convoy to the Al-Aqtan prison in Raqqa. The geospatial features align with Raqqa’s checkpoint (35°58’34.6″N 39°01’57.7″E) on the M6 highway, which leads to Al-Aqtan prison, and the author believes this video was filmed there.

Conclusions

Digital evidence from al-Hol overwhelmingly rules out any scenario in which STG forces arrived at the camp substantially after the SDF withdrawal, later “that evening”, or in the following morning. Footage from the camp supports a timeline in which STG forces took over SDF control positions with a minimal delay, likely less than 60 minutes.

In fact, the news reports about the STG forces arriving at the camp on the following morning appear to stem from a misinterpretation of the AFP photojournalist cited as a source in the France24 article: the source did not witness the arrival of the army but the later deployment of an affiliated police force, as clearly shown by the “Internal Security Command” markings on their cars.

Digital evidence also contradicts the reported causal link between the SDF withdrawal and the “triggering [of the] unrest that forced aid agencies to suspend operations.” The first signs of SDF pullback surfaced around 2:30 PM, by which time a riot was already well underway inside the camp, and an external attack was ongoing. According to the former camp director, aid agencies were not present at the camp that day due to the actions of STG-affiliated forces on the roads–a credible claim in light of available evidence.

The near-simultaneous armed uprising in al-Hol, the riot inside the camp, and the arrival of STG forces suggest at least some degree of coordination between local groups, ISIS, and STG. However, the only clear evidence of such coordination is the post on the ISIS-affiliated Facebook page that informed its followers that STG forces were arriving and urged them to launch a riot inside the camp.

Finally, footage from the camp shows at least two separate outbreaks: one in the main camp and another in the high-security annex. The same videos show STG-affiliated fighters overlooking and encouraging the mass escape rather than attempting to contain it.

The precise number of escapees cannot be established or verified from publicly available sources. The ISIS channel referred to previously claimed that 200 people escaped, but the real number can be anywhere from dozens to thousands. Public sources also do not indicate whether any of the runaways were later captured.

Regarding these questions and several other aspects of the reporting, the author requested comments from the Syrian Ministry of Defense. As of the time of publication, the ministry had not responded to the emailed questions.

Henri Sulku

Henri Sulku is a journalist whose work focuses on Syria and the broader Middle East. For more than a decade, he has researched how insurgent and other non‑state actors shape the region’s political landscape. Currently, he works as an editor at Turning Point magazine.