How Azadi Park Shaped Slemani’s Political Memory

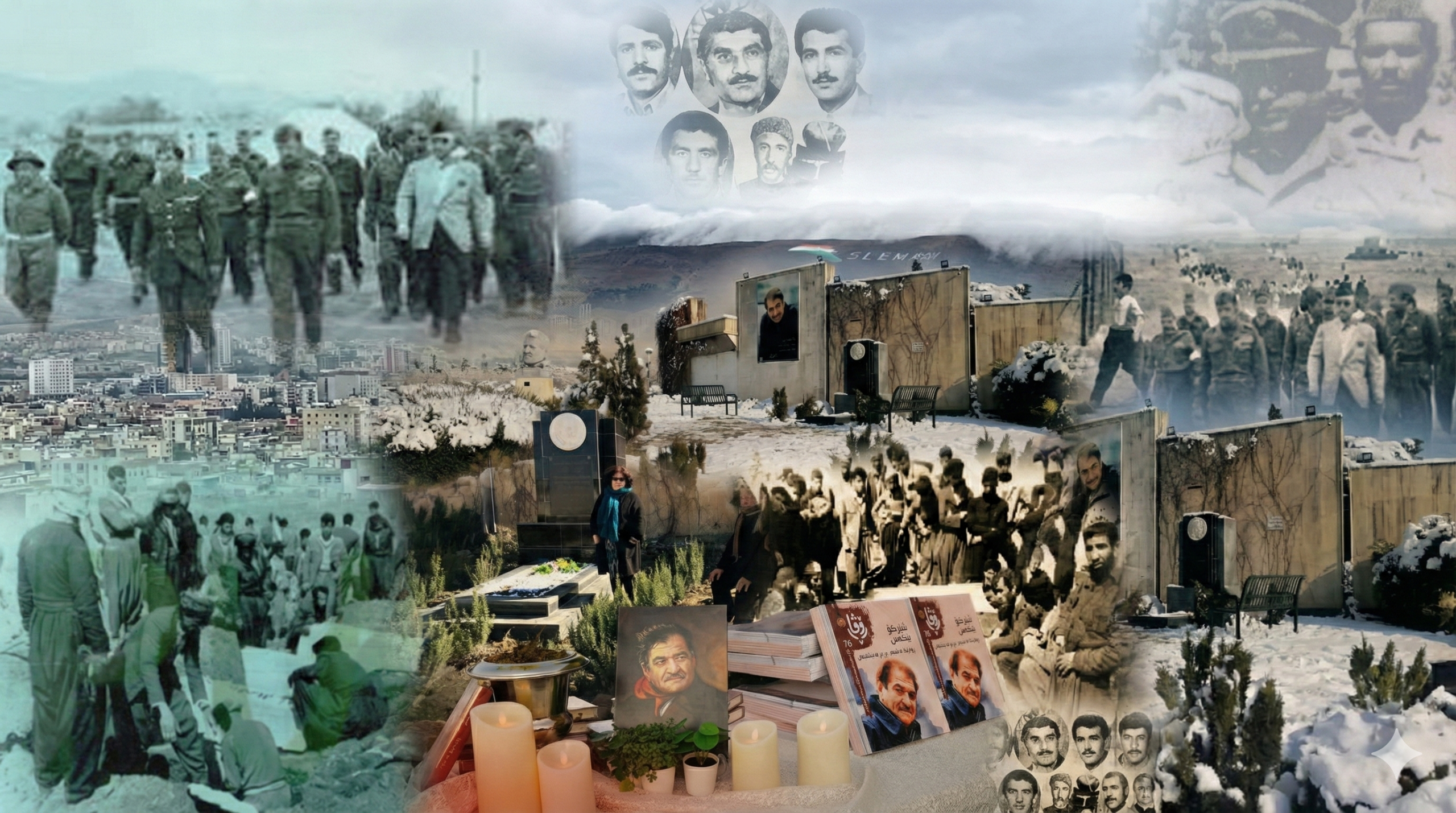

A century of Slemani’s (Sulaymaniyah) history is in Azadi Park. Since 1924, various powers used the site as a military post: many soldiers have marched out from its gates, innumerable civilians have been pulled inside for questioning, and generations have tremored with fear at its sight. It has stood through rebellions, coups, the long years of Baathist repression, and the hope that followed the 1991 uprising.

Throughout the Hashemite Monarchy’s reign, when Iraq was first born as a state in 1921, the park’s site was a symbol of repression and a center for controlling the population and silencing dissent.

After Sheikh Mahmud Barzanji’s last administration fell in 1924 – in which he tried to establish an independent Kurdistan – the British-backed Iraqi government took control of Slemani and stationed troops where Azadi Park now stands. The authorities watched the city from that location, and from then on, the site served as a military base, monitoring movements and responding to any uprisings.

Baathist and Iraqi Rule

On September 6, 1930, a date referred to as the “Dark Day,” people protested the Iraqi government’s decisions, denying Kurdish rights, self-rule, and fair political participation. The government responded by mobilizing Iraqi forces at the military base and sending them to the city center, where they killed, wounded, and detained civilians. The Dark Day solidified the site’s associations with state repression.

A decade later, the Iraqi government stationed cavalry units at the base, strengthening their control over the town and saturating the park’s reputation as a place of fear and coercion.

During Iraq’s Baathist era, 1963—2003, the park witnessed unprecedented brutality. In 1963, after the Baath Party took power, the new regime wanted to exert dominance over Slemani because of the city’s support for the Kurdish movement and the Kurdish leader Mulla Mustafa Barzani. For that purpose, the Baathist regime reinforced the military post at the edge of the park and used it as a barracks, renaming it Hami of Slemani.

“During Iraq’s Baathist era, 1963—2003, the park witnessed unprecedented brutality. In 1963, after the Baath Party took power, the new regime wanted to exert dominance over Slemani because of the city’s support for the Kurdish movement and the Kurdish leader Mulla Mustafa Barzani.”

In the skirmishes of this era, the Iraqi army struggled against the Kurdish Peshmerga rebels, as a result Commander Sidiq, leading Brigade 20, was sent to Slemani to control it. At dawn, on June 9, 1963, forces at Hami took to the streets with megaphones and announced a curfew and ordered residents to remain indoors and launched raids across the city. Civilians were killed, wounded, and detained, with the barracks as the center of the crackdown, serving as both military outpost and prison.

By the end of the operation, the army had killed around 100 people and arrested an estimated 5,000, and numerous suburbs of Slemani were destroyed. It was the first massacre by the army inside an Iraqi city.

Under Saddam Hussein, the Baath Party expanded the prison and built towering walls around the barracks. In 1985, during a curfew imposed to curb public demonstrations, Hami again became a hub of repression.

“Azadi Park once again became a site for attacks, this time against creativity and expression. Artists were insulted, and numerous statues and monuments were secretly destroyed, including the Love Statue and the grave of Sherko Bekas in 2013.”

Once more, soldiers attacked civilians, arrested thousands, and held them at the facility. Adding to the compounded terror the Baathists doled out, they also began using the site as a helicopter base, whence the regime launched assaults on the Peshmerga in surrounding villages while maintaining control over the town.

Ironically, Hami’s history of cruelty did not end when the Baath regime was ousted from the Kurdistan Region in 1991.

When Kurdish uprisings took control of northern cities, the symbol of state repression became a tool for the new authorities.

After the uprising, the Iraqi regime retook Kirkuk while most Kurdish-majority cities remained under Kurdish control, leaving Kirkuk’s Kurdish residents vulnerable to reprisals and forced displacement. As a result, many Kirkukis were prevented from returning and were dispersed to Erbil, Duhok, and Slemani.

Kurdish militias targeted residents resettled from Kirkuk and other areas, and those who resisted faced attacks. Among the victims was the young poet Bakir Ali, who had fought for social and political equality and demanded basic rights. His death marked not only a tragic loss but also a grim reminder that cycles of violence persisted, as the fourth deadly civil war erupted among rival Kurdish factions.

Kurdish Rule

Despite the land’s gory history, Jalal Talabani, former Iraqi president and secretary-general of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), converted Hami into a public space, naming it Azadi Park (Freedom Park) in 1994. He later added Sakoy Azadi – Freedom Stage in 2003. Talabani transformed the area, long a symbol of repression, into a platform for free speech and open critique, including critique against himself.

The park has held several symbols of liberty and courage: the Love Statue; the grave of Sherko Bekas, one of the greatest Kurdish poets and a major supporter of human rights and freedom of expression; statues of artists and poets, including Qanî, the poet of the poor, who spoke for workers and low-income communities; and the names of the martyrs of the Dark Day of September 1963, serving as a reminder of resistance. Talabani had created a site for political activity and expression.

With this transformation, a new era of freedom emerged. Residents used the park for leisure, and it became a meeting place for lovers, even as the city remembered the tragic past.

After the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003, a wave of Salafism spread across Kurdish cities in the Kurdistan Region. Maintaining good relations with the ruling parties, the PUK and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), these groups faced little opposition as long as they did not challenge the parties’ authority.

“Azadi Park, once and briefly a symbol of free expression, now stands as a solemn reminder of the fragility of freedom and the price paid over the past century.”

The Salafists exercised considerable freedom: they interfered in private life in Kurdistan, banned many forms of art, and suppressed joyful celebrations, such as celebrating Newroz and the celebration of Prophet Muhammad’s birthday.

Azadi Park once again became a site for attacks, this time against creativity and expression. Artists were insulted, and numerous statues and monuments were secretly destroyed, including the Love Statue and the grave of Sherko Bekas in 2013. Park authorities later reported that 12 statues and busts had been defaced or demolished during the 2010s – a decade marked by crackdowns on democracy and freedom of expression in Kurdistan.

Jalal Talabani died in 2017 after a prolonged illness. His family retained control of the PUK, and in 2019, his son Bafel Talabani was elected co-chair alongside his cousin Lahur Sheikh Jangi.

In the following years, the party’s internal conflicts led to further concentration of authority within a small circle. Across the city, conditions worsened; repressive measures intensified, including targeted assassinations, kidnappings of journalists and writers, raids on homes, and restrictions on public gatherings. Protests against foreign interference, particularly by Turkeyand Iran, were banned, and demonstrators faced arrests.

Azadi Park, once and briefly a symbol of free expression, now stands as a solemn reminder of the fragility of freedom and the price paid over the past century.

Diary Marif

Diary Marif is a Vancouver-based writer and freelance journalist. He holds a master’s degree in history from Pune University, India, 2013. He received an Honourable Mention for the 2022 Susan Crean Award for Nonfiction, is a 2025 recipient of the Yosef Wosk Vancouver Manuscript Intensive Fellowship, and was awarded PEN Canada’s 2025 Marie-Ange Garrigue Prize in 2025.