Öcalan’s Quiet Leverage: How İmralı Shaped Rojava’s January De-escalation

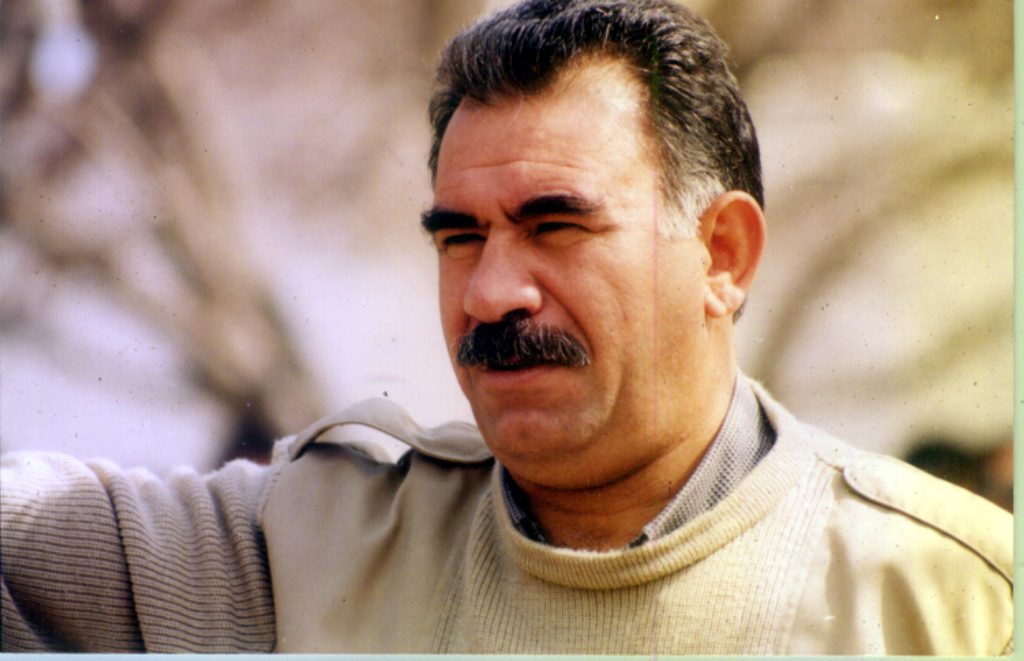

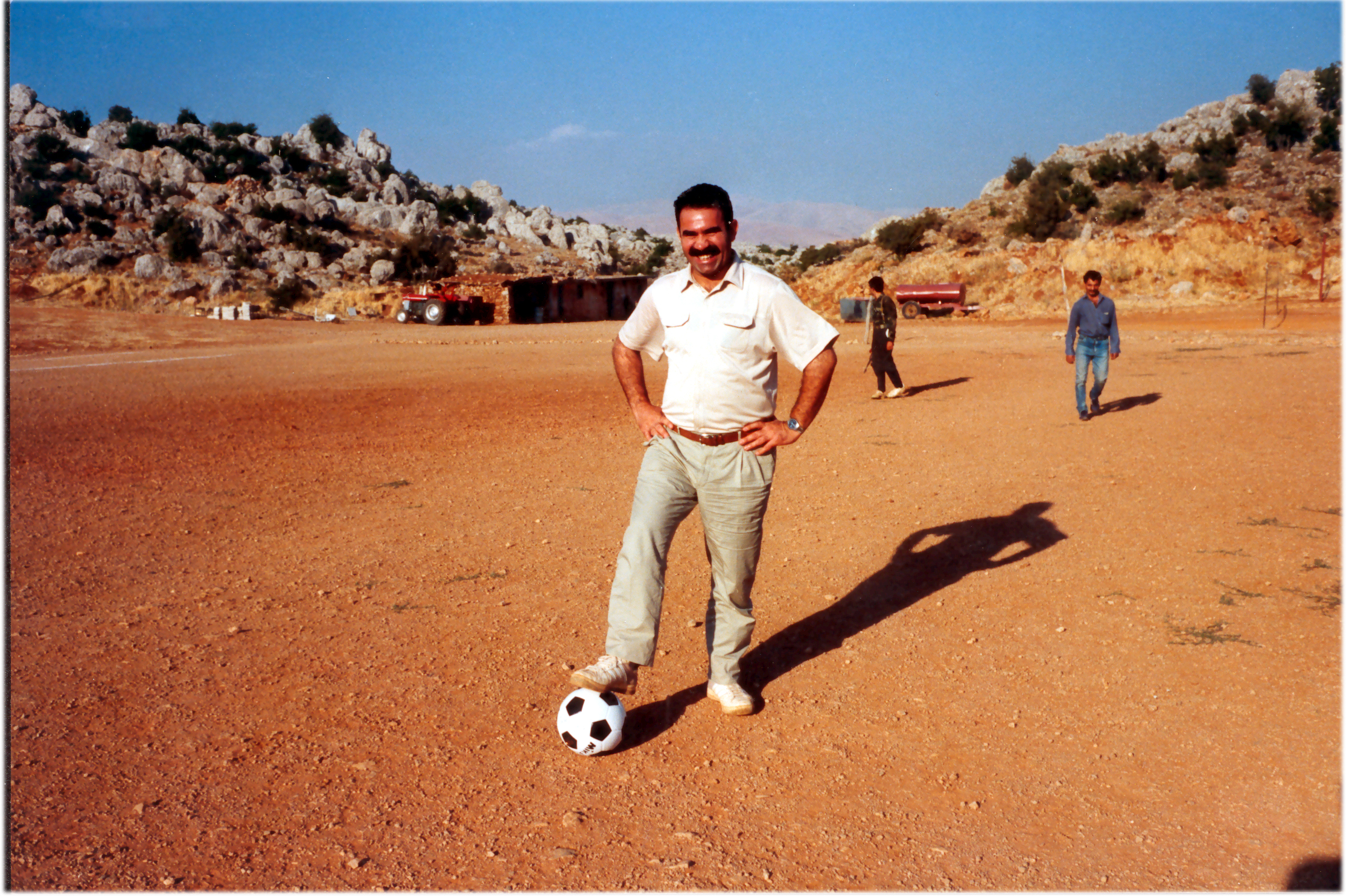

The late-January agreement between the Syrian Democratic Forces and Syria’s interim authorities arrived with little fanfare and many ambiguities. Publicly, it looked like an imperfect compromise hammered out under pressure. Within Syria, it stopped a rapidly expanding war that threatened to unravel the progress made by more than a decade of Kurdish self-rule in northeast Syria. Multiple political sources tell The Amargi that a decisive, if largely concealed, hand belonged to Abdullah Öcalan, whose strategic interventions from İmralı Island helped redirect events away from escalation and toward containment.

The Amargi spoke with two sources in Turkey and one source in Syria to confirm the contours of this account, especially the recent report by Yeni Yasam. All requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the ongoing process. Their testimony aligns with statements later made by parliamentary and legal figures who have direct access to İmralı.

A war that nearly was

In early January, armed groups affiliated with the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham-led Syrian Arab Army, alongside Turkey-backed factions, launched heavy attacks on Kurdish neighborhoods in Aleppo – most notably Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafiyeh. Clashes soon rippled toward the Kurdish-held areas in Raqqah and Deir Ezzor, placing the entire Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria under existential strain. Kurdish forces mobilized, but the political temperature rose just as fast: diplomats and power-brokers began to treat the crisis as an opportunity to “reorder” the northeast.

For years, Öcalan had described Rojava as a “red line,” arguing that any regional settlement that sacrificed Kurdish self-rule would be morally indefensible and strategically explosive. This strong position was partly the reason the Kurdish-Turkish peace process in 2015 collapsed, as the Turkish state rejected accepting a self-rule Kurdish enclave in Syria. According to sources familiar with the process, Öcalan reiterated that view as pressure mounted on the Autonomous Administration to dissolve its military and administrative structures. His guidance to Kurdish leaders was practical, not maximalist: borders, airports, and revenue management could be negotiated; self-defense, decentralized governance, and cultural rights could not.

Why the Kurdish side stayed quiet

One puzzle dominated Kurdish public debate as the crisis unfolded: why did the İmralı delegation and broader Kurdish movement say so little while state actors spoke freely and shaped the narrative?

According to those close to the talks, the silence was deliberate. The Kurdish side, starting with the İmralı delegation, chose restraint out of fear that any misstep could derail a fragile process. This caution stood in stark contrast to Ankara’s approach, where officials and aligned media filled the vacuum. The imbalance mattered. In 2015, the state was more guarded, while Kurdish actors spoke openly; in January 2026, the roles reversed. When this asymmetry was later weaponized to suggest that Öcalan was either irrelevant or complicit, Kurdish actors panicked and rushed to clarify their positions. The content of Öcalan’s interventions was not unexpected. The timing and the cost of silence became the controversy.

A stalled deal and a dangerous detour

In December, Damascus circulated a draft accommodation framework. Talks intensified and culminated in a January 4 meeting in Damascus under U.S. and French observation. Participants discussed a comprehensive arrangement and even prepared a public declaration. Then the process abruptly stalled. According to diplomatic sources, the Syrian foreign minister left the room, returned with instructions, and halted the signing.

What followed was a parallel diplomatic detour. Kurdish sources say negotiations shifted to Paris, where arrangements involving HTS and Israel were discussed under U.S. oversight and reportedly encouraged by the United Kingdom. The emerging logic of tacit acceptance of HTS expansion into Kurdish-held areas set off alarm bells. Kurdish fears of an internationally sanctioned rollback of autonomy surged.

Public reaction was immediate. Protests erupted across Kurdistan and the diaspora. For the first time in years, Kurds from all four parts mobilized around a single demand: defend Rojava. This backlash coincided with renewed activity centered on İmralı.

Öcalan draws a line

Sources say Öcalan requested urgent meetings with Turkish officials and warned that the unfolding plan resembled a comprehensive conspiracy against the Kurds, larger, in his words, than the plot that led to his own capture in 1999. If implemented, he argued, it would not stop in Rojava but spread to Sinjar, southern Kurdistan, and the Qandil Mountains. Anxiety reached the Iraqi political parties, especially the Shi’as, who subsequently moved the Iraqi Army and the Popular Mobilization forces, known as Hashdi al Sha’bi, to the border with Syria to be prepared for any urgency.

“No one can destabilize Rojava and expect me to consent.”

When presented with a six-point proposal attributed to Damascus and HTS, later reflected in a draft floated on January 18, Öcalan categorically rejected it. He reportedly called the text a blueprint for Kurdish elimination and asked why comparable demands were not imposed on other communities. He repeated this position during a January 17 meeting with a DEM Party delegation, warning that any settlement imposed by force would be illegitimate.

His message to Ankara was frank: continue on this path, and he would withdraw from dialogue altogether. “No one can destabilize Rojava and expect me to consent,” he reportedly said.

Resistance, consolidation, and leverage

As clashes intensified, the Syrian Democratic Forces redeployed from Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor to consolidate east of the Euphrates. Even then, attacks continued. Öcalan’s guidance was clear: if annihilation was the objective, resistance was the only rational response.

A ceasefire announced in Damascus on January 18 failed to force a one-sided agreement when the SDF delegation walked away. Backchannel contacts multiplied, linking Ankara, Qamishli, Damascus, Erbil, and Washington. Kurdish unity on the streets and coordinated diplomacy by regional Kurdish leaders shifted the calculus. International actors recalibrated.

At Öcalan’s insistence, a broader meeting convened in northeast Syria, bringing together representatives of Turkey, the Autonomous Administration, Damascus, and U.S. and French officials. The purpose was to end secret deals and put red lines on the table. Three principles were declared non-negotiable: self-defense, decentralized governance, and language and education rights.

The January 30 framework

The talks produced the framework that underpinned the January 30 agreement, later signed in Damascus and announced publicly. The text is imperfect and ambiguous. But even skeptics concede it blocked a coordinated effort to dismantle Kurdish gains by force. It also restored a measure of predictability at a moment when miscalculation could have triggered a regional conflagration.

Parliamentary confirmation

The Amargi also spoke to Berdan Öztürk, an MP for Diyarbakir (Amed) from the Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party), who confirmed the core of this account. “No political settlement exists without Öcalan,” he said. “Öcalan is the mastermind behind saving Rojava and the agreements.”

“Raqqa is not Kurdish. Compromising on such areas to preserve the Kurdish gains and prevent the region from a civil war is a success.”

Öztürk added that Öcalan urged Kurdish actors “to get together and save Rojava by resistance or by diplomacy.” The instruction was not binary. “Öcalan said resist, and also make the March 10 agreement a reality. He sent messages to everyone and urged everyone to work for peace.”

On the sensitive question of withdrawals, Öztürk emphasized pragmatism. Pulling back from Raqqa, he said, was not a concession. “Raqqa is not Kurdish. Compromising on such areas to preserve the Kurdish gains and prevent the region from a civil war is a success.” He also stressed the importance of mass mobilization: Kurdish resistance across regions gave Rojava leverage, forcing the international community to respond. “These are not the Kurds of the early twentieth century,” he said.

Neither Messiah nor ghost

A final corrective comes from Faik Özgür Erol, who has been Öcalan’s lawyer for 19 years, and who relayed Öcalan’s own caution against mythmaking. Over the past year, Erol said, Öcalan repeatedly stressed that he is “neither the Messiah nor a ghost.” Some treat his words as prophecy; others act as if he were politically dead. “Neither corresponds to reality,” Öcalan argued. Politics, in his view, begins with acknowledging facts and choosing the rational, not the ideal, not the perfect, but the workable.

This ethic helps explain January’s restraint and its risks. Silence was meant to protect a process; it also allowed others to define it. When the cost became clear, interventions followed, firm, strategic, and focused on outcomes.

What January revealed

…even in isolation, Öcalan’s calculations can still redirect a war toward a pause…

Two conclusions stand out. First, no durable arrangement in Syria can bypass the Kurds. Attempts to do so generate resistance that quickly spills beyond borders. Second, despite decades of imprisonment, Abdullah Öcalan remains a consequential political actor. His leverage does not come from spectacle or proclamations, but from the ability to set red lines, align disparate Kurdish actors, and convince external powers and Kurdish leadership in Turkey and Syria to reckon with realities on the ground.

January’s agreement may not settle Syria’s northeast. But it proved that even in isolation, Öcalan’s calculations can still redirect a war toward a pause and buy time for a politics that remains unfinished.

The Amargi

Amargi Columnist

![[The Amargi Exclusive] Investigating the Syrian Army’s Abuses](https://cms.theamargi.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/AFP__20260118__934D2KE__v1__MidRes__SyriaConflictKurds.jpg)