Tension and Clashes Shake Kurdish Neighborhood in Aleppo Amid Fragile Ceasefire

Uncertainty prevails in the Kurdish-majority neighborhoods of Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafiyeh in Aleppo. After several hours of clashes on Monday night between Syria’s General Security forces and the Kurdish Asayish, the area is now under a fragile truce.

On 6 October, fighting broke out between the Syrian General Security forces and members of the Kurdish Asayish in Aleppo. The Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafiyeh neighborhoods, under Kurdish control, were besieged after increasing confrontations along various points of the frontline between the Autonomous Administration of North East Syria’s (AANES)-controlled areas and the new Damascus government.

The Syrian army mobilized tanks, mortars, and a large number of soldiers toward the Kurdish-controlled neighborhood checkpoints. Entrances were closed to enforce an effective blockade.

The Syrian army mobilized tanks, mortars, and a large number of soldiers toward the Kurdish-controlled neighborhood checkpoints. Entrances were closed to enforce an effective blockade. “We felt like our freedom was restricted like in an open-air prison,” said Muhammad, a journalist residing in Sheikh Maqsoud who prefers to remain anonymous. “Internet and electricity services were also cut off, no food or medicine entered, and students and patients couldn’t leave. This caused a lot of psychological distress,” he told The Amargi.

“The situation escalated after a clash in Deir Hafer, East of Aleppo, between the SDF (Syrian Democratic Forces, the AANES’s military branch) and General Security,” said Manar, 23, a resident of Sheikh Maqsoud. The young English literature student explained that the rising tensions led the government to increase its presence to encircle all Kurdish-dominated areas. The deployment of military equipment along the frontlines near the two neighborhoods forced the Kurdish Asayish forces—backed by the SDF—to reinforce their defenses. Tensions rose to the point where it became unclear who fired the first shots.

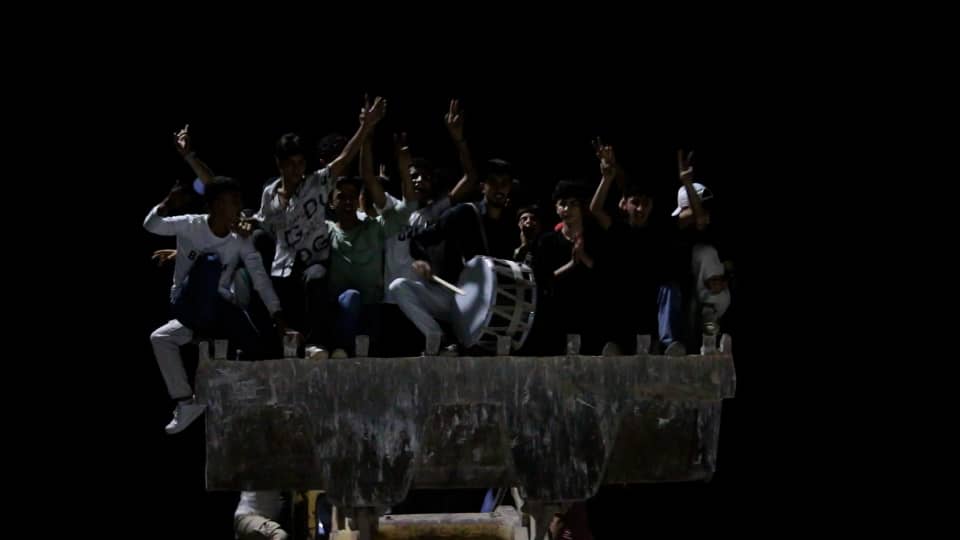

Residents found themselves trapped under crossfire in the vast Kurdish districts of Aleppo. The tension was succeeded by spontaneous protests near the blockade checkpoints. “People were calling for the SDF to return to the neighborhood to protect them,” Manar told The Amargi, referring to the earlier withdrawal of SDF forces following the implementation of the March 10 agreement. Recent massacres targeting Druze and ‘Alawi communities have deepened distrust in the government’s ability to ensure the safety of ethnic and religious minorities.

“When the protesters began calling for SDF intervention, the army fired tear gas at them, and the demonstrators threw stones in defense,” Manar reported over the phone from inside the neighborhood. “Repression turned violent when security forces began shooting at people,” she added. The hospital was filled with wounded civilians, and the streets were blood-stained. The protest escalated into armed clashes overnight between government military forces and the Asayish. According to pro-regime agency SANA, one government soldier and one civilian were killed in the Monday night confrontation.

A Fragile Ceasefire

An AANES delegation, including SDF general commander Mazloum Abdi, met on Tuesday with officials in Damascus to negotiate the integral ceasefire on all fronts. An “integral ceasefire agreement” is now in effect after several hours of warlike scenes in what became the most serious confrontation between the two forces during Syria’s transitional period.

While both parties sought to revive the March 10 agreement—brokered by U.S. officials— implementation has stalled, and tensions have increased. After the latest meeting, social media reports indicated that there was no progress. In other regions of the Euphrates, this truce was broken several times.

Since Ahmad al-Sharaa ousted Bashar al-Assad from the presidency in December 2024, the Kurds have found themselves caught between military escalations and diplomatic negotiations. The SDF resists integration into a government led by their former adversaries, including the officially disbanded Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) whose former members form the bulk of the current Syrian Interim Government. “[Damascus] is repeating the same patterns as the old regime—we don’t feel recognized. For example, Newroz isn’t even an official holiday,” Manar said.

“Everything is About to Explode”

The outskirts of Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafiyeh are packed with people hoping to reunite with their loved ones in the neighborhoods. Dozens sit with worried expressions, their sobs blending with the shouts of officers telling them to move: “Back! Back! There’s a sniper; clear the area.”

/im

For two days, the idea was “Once you leave, you can’t come back,” as allegedly stated by a General Security officer at the checkpoint on al-Zohoor Avenue in Ashrafiyeh. Among the armed men dressed in black, a child runs joyfully into his father’s arms at the edge of the neighborhood. The joy of their reunion adds a moment of sweetness amid the chaos.

However, after 48 hours of total lockdown, residents are trickling back, but “only 3 of the 7 passages connecting the two neighborhoods with the rest of Aleppo city are open: the al-Ashrafiyeh park passage, Dawwar al-Shihan, and al-Awaarid,” says Muhammad. “In a way, it’s still half a siege,” he continues. “If the Deir Hafer road, which connects the two neighborhoods to northeastern Syria [controlled by the SDF], stays closed, it will cause a humanitarian problem, especially for providing heating for the winter. If diesel doesn’t arrive soon, it will be problematic,” he added.

“They also subject the civilian population to exhaustive searches and inspect their mobile phones when crossing between the two neighborhoods…”

Despite the reopening of the roads leading to Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafiyeh, “the siege continues through other means,” says Qadi Mihemed, a resident of Sheikh Maqsoud. “General Security forces from the Interim Government have established new checkpoints in addition to the existing ones, increasing restrictions on civilian movement,” he explains. “They also subject the civilian population to exhaustive searches and inspect their mobile phones when crossing between the two neighborhoods, which concerns residents, who see this as a violation of their freedom of movement and privacy.”

About 400,000 people live between the two neighborhoods, which have been partially isolated from the rest of the city since forces led by Ahmad al-Sharaa took control of Aleppo during a lightning offensive that culminated in the fall of the Assad regime.

Since then, the Kurdish population has been displaced mainly by attacks from militias affiliated with the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army, a group of proxy militias responsible for serious war crimes over the past years.

Within the new government forces, “there is no unified leadership,” says Muhammed. He adds with concern, “We saw the mistakes made by the Ministry of Defense members on the coast, in Suweida, and even in Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafiyeh.” According to Muhammad, “there are still factions following Turkey’s orders, and if these factions are around the two neighborhoods, they will cause problems in the future,” he said, referring to Turkey’s broader strategic objectives of militarily crushing the PKK and YPG’s aspirations for self-determination.

An Uncertain Future

The landlocked neighborhoods of Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafiyeh in Aleppo have been under the control of the AANES since 2015. After the March agreement with Damascus, the SDF began their withdrawal, leaving security in the hands of the Asayish and exchanging prisoners with the government. In recent months, mutual accusations have emerged between checkpoints where snipers killed neighborhood residents. Meanwhile, in Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa, brief clashes broke out.

For now, the ceasefire remains fragile, but no party can afford an all-out war. Meanwhile, a political deadlock further deepened after the AANES districts were excluded from Syria’s first parliamentary elections since the end of the al-Assad regime. The excuse was that they were outside government control, but this was widely criticized by the inhabitants of the regions, who felt marginalized.

The current clashes reveal serious structural problems within post-Assad Syria. Foreign interventions have armed militias across Syria who share divergent, sometimes conflicting agendas.

The current clashes reveal serious structural problems within post-Assad Syria. Foreign interventions have armed militias across Syria who share divergent, sometimes conflicting agendas. Many have developed narratives revolving around their sectarian or ethnic identity to strengthen their autonomy in the name of protection. This, however, also fractures internal relations within Syria, not only politically but also territorially, making it difficult to overcome divisions today for the construction of a unified country.

Muhammad worries that the new government will reaffirm a national identity tied to “one ethnicity, one flag, one language, neglecting diversity.” For him, “If this mentality persists, we will reach a point where a new civil war will explode, not just in these two neighborhoods, but all over Syria. The exclusion of others and our failure to accept each other will drag us into new wars.”

The Amargi

Amargi Columnist