How Poverty Leaves Alawites Exposed to Sectarian Violence in Hama

Picture Credits: Santiago Montag

Photo Credit: Santiago Montag

This article was co-authored by Angela Asahwi and Santiago Montag.

The village of Jadrin in the Hama countryside has become the grim scene of a tragedy. The townspeople witnessed a brutal crime in which armed attackers murdered four young people in the prime of their lives in cold blood.

On the 28th of September 2025, Ali, Rabieh, and Mehsen Zeydan, alongside Youssef Youssef, were returning home after a long day of work. After riding their motorbike several kilometers from the neighboring village of al-Houleh, they did not find a comfortable mattress with a hot meal waiting for them. Instead, their fate would be steeped in violence, ending their lives in tragedy.

“I heard the sound of the motorbikes arriving home, so I went out onto the terrace to wait for them,” said Hasna, Ali’s sister. The village is very small, in the middle of a vast green landscape. Everyone knows each other, and everyone always waits for their family members to return from work. “Suddenly, I saw that a motorbike had intercepted them, and the men riding the bike started shooting at them,” she said with tears in her eyes and a broken voice. “I tried to go and help them, but my husband stopped me. He told me I would suffer the same fate,” she claimed. “They shot them several times to make sure they were dead. I saw how they killed my brother.” Her balcony is located about 50 meters from the crime scene, which is clearly visible from her home. This is why she says that her “heart is broken”.

Hasna was able to identify two gunmen on a large motorbike. After the crime, instead of escaping via a supposedly safe route, they entered the village — likely demonstrating their control over the situation.

Less than 45 minutes after the attack, relatives of the young men received a call from the Syrian Interim Government authorities announcing that they had caught the perpetrators. On social media, the Ministry of the Interior announced that they had captured three men linked to the murder, without revealing their identities. “I’m not sure if they are telling the truth. We don’t know if it’s true,” said Mehsen’s 22-year-old sister.

Jadrin is a predominantly ‘Alawi village with Sunni villages in the neighboring area. Rami, the village mukhtar, tells The Amargi. “We live in harmony with our neighbors. They are our brothers. We all know each other; those who came here to attack us are not from the area”. Rami is astonished by the incident. “What we have in common with our neighbors is poverty,” he added.

Sectarian escalations

Since the new government took power in December 2024, Syria has undergone several crises that have claimed thousands of lives. On the coast, massacres against ‘Alawi followed an uprising by groups linked to the former regime in March left more than 1,500 people, mostly civilians, killed by Salafist groups linked to the new rulers. In Suweida, nearly 2,000 people were brutally murdered, mostly Druze civilians. Currently, tensions are rising with the Kurds in Aleppo. All of this raises the suspicion that the attacks in rural areas are not random violence, but targeted sectarian campaigns.

The inhabitants of Jadrin are indeed convinced that the recent attack was sectarian in nature.

The inhabitants of Jadrin are indeed convinced that the recent attack was sectarian in nature. Although they consider the perpetrators to be outlaw gangs, they believe that they are being targeted because of their religious and community status.

“This was not the first massacre. This time our family lost three young people, but months before this, they killed three others, including a child,” explains Rabieh Zeydane’s father.

Indeed, a pattern of attacks has been occurring since the fall of the al-Assad regime. Jadrin has suffered around 10 violent attacks ever since, several of which resulted in deaths. This is a high number for a village of 2,500 inhabitants.

The first attack happened on 24 December 2025; Mahmoud, Rabieh’s brother, was shot in the abdomen by an unknown gunman. “The bullet was poisoned; it began to infect his body,” their father claimed during his son’s funeral. His family fought for eight months to save the 19-year-old’s life before he finally died at home.

His initially non-fatal wound became fatal due to the lack of health services in the area and the difficulty of travelling to the city for treatment. If there had been a clinic in the village or a hospital nearby, Mahmoud might still have been alive and recovering.

The issue, therefore, goes beyond the bullet wound caused by a crime charged with sectarianism. Such incidents expose the fragility of Syria’s current reality and the weakened resilience of communities rendered unable to withstand further blows after years of exhaustion, compounded by systematic marginalization and neglect.

At the end of August, two more members of the Zeydan family were killed, one of them a young child. The family was still mourning their loved ones when Ali, aged 22, was killed in his dusty work clothes last week.

Beyond sectarianism, Syrians face hardship due to class and institutional neglect. The daily struggles of workers moving between countryside and city are shaped by the abandonment of rural areas in favor of urban ones and the absence of even the most basic conditions for life.

Cheaper than the bullet that killed them

“The villagers did not support the old regime; on the contrary, we have been victims of Assad.”

During the al-Assad era, the ‘Alawis of Jadrin, like other Syrians, were forced to join the army. For many, it was a way to meet their basic needs, but “many have escaped, hiding here and there to avoid military service,” explains Rabieh’s mother. She firmly states that the villagers “did not support the old regime; on the contrary, we have been victims of Assad.”

Now, they live in constant fear, as sectarian killings have become commonplace. Fear prevents them from working in the few jobs available. “We have no choice, but if we leave the village to work, we don’t know if we’ll return home alive,” says Mehsen’s brother. “Our wages range from 30,000 to 50,000 Syrian pounds per day (between 3 and 5 USD). We take turns going to work, and our families are large,” he explained.

By mid-January, about 300,000 state employees had been dismissed. Although the layoffs affected all sects, ‘Alawis were disproportionately impacted, reflecting both sectarian discrimination and the fact that many had originally been hired as “relatives of martyrs” under the previous regime. Under al-Assad, government jobs had served as a form of compensation for the families of soldiers and security personnel killed in action, which had led to the hiring of thousands of employees without real administrative need.

The swift elimination of this privilege was among the first measures taken by the al-Sharaa transitional government. This move —portrayed in the media as a gesture of justice toward the victims of the regime — was, in reality, an ill-considered act of collective punishment. Thousands of families had depended primarily on those salaries, with no alternative means of livelihood. This situation left them without any source of income to meet even their most basic needs.

As a result, many young people, who previously relied on the salaries of their relatives who were former retired or deceased soldiers, had to seek new ways to earn an income. Although the so-called “martyrs’ compensations” had never been large enough to cover families’ full needs, they had at least provided a minimal lifeline amid a collapsing economy, worsening living conditions, and rising unemployment.

Shouts in a wooden bell

The ‘Alawis in Jadrin now live in limbo between poverty and abandonment under the new authorities…

The ‘Alawis in Jadrin now live in limbo between poverty and abandonment under the new authorities, harassed by sectarian violence without clear attackers, thus remaining under constant terror with nowhere to escape. All they can do is stick together, demand justice, and ensure that the state guarantees their physical survival as part of the new Syria.

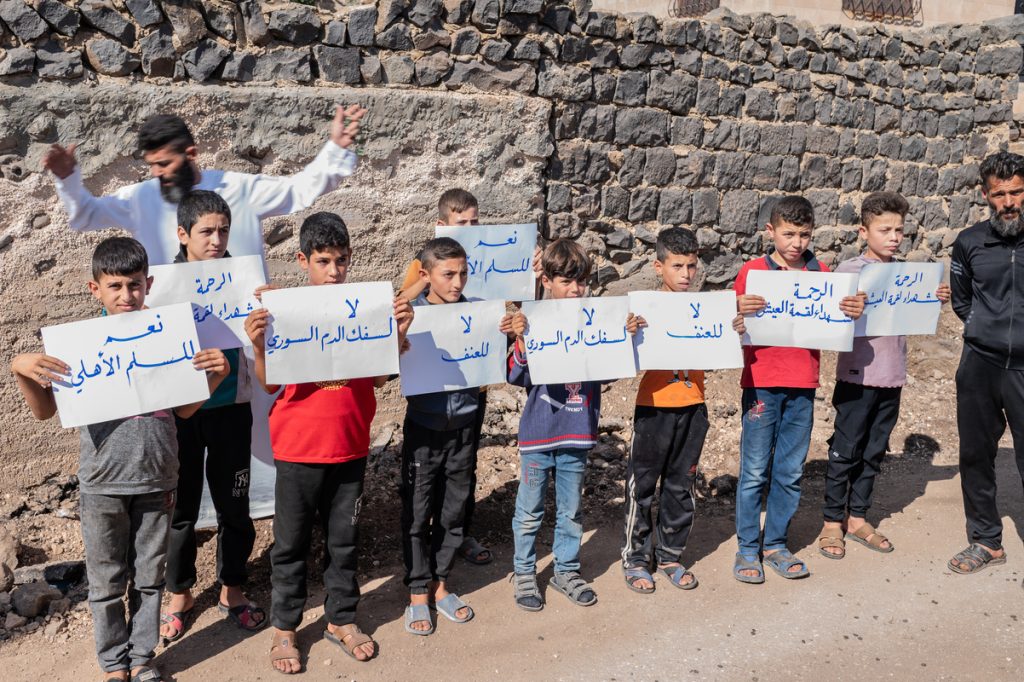

To honor their victims, the residents of Jadrin have decided to protest peacefully, behind banners calling for an end to the bloodshed, regardless of who is responsible. More than 40 neighboring towns in Hama and the rural areas of Homs have joined the sit-ins, where they even called for a general workers’ strike.

Perhaps the cry behind the banners carried by children can convey, at least to some extent, the depth of the tragedies still weighing on the community. Unless the new Damascus government takes structural measures to change a situation that has been stagnant for years, these children are doomed to inherit a cycle of violence.

Santiago Montag

International journalist and photographer based in Damascus