China’s Soft Game on the Kurds: Between Pragmatism and Power Politics

As China’s global ambitions expand under the new leadership, its foreign policy is undergoing a gradual but distinctive transformation. Its policy goes from watchful non-alignment to strategic engagement. For China, the Middle East, which has long been dominated by Western powers and regional rivalries, has emerged as a crucial zone to extend its influence. Within this contested geopolitical landscape, the Kurdish question presents both a latent opportunity and a profound diplomatic dilemma for China.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is considered the backbone of its engagement with the Middle East. Through investments in energy infrastructure, ports, telecommunications, and trade corridors, China has established itself as a key economic actor across the region. Unlike Western powers that have historically relied on military force, regime change, or ideological intervention, China projects soft power through economic integration and diplomatic neutrality, highlighting sovereignty and non-interference.

This formula has produced notable advantages. China’s mediation of the 2023 Saudi–Iran rapprochement was more than a symbolic success. In fact, it has marked China’s debut as an effective political broker in a region that has historically been shaped by Western dominance. Yet this growing diplomatic confidence raises a question: could China apply the same soft tools to one of the region’s most complicated conflicts?

The so-called Kurdish question links more than 40 million Kurds through a shared experience of statelessness and suppression. Each of the states that the Kurds live in views Kurdish political mobilization as an existential threat to territorial integrity.

For decades, external powers have instrumentalized Kurdish movements as tactical allies rather than genuine partners. One recent example is the support of Kurds against ISIS, only to then abandon them when strategic interests shifted. At this very moment, China enters this landscape not as a traditional military actor but as an economic giant whose investments could reshape the material and political realities of the region. Yet its rhetoric of neutrality and sovereignty collides directly with the Kurds’ central demand, which is the call for self-determination.

China’s growing presence in Iraq and Syria already has indirect consequences for Kurdish politics. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) has actively courted Chinese investment in energy, construction, and higher education, seeking to diversify beyond Western and Turkish dependence. Though limited, these speculations symbolize the KRG’s recognition of China’s rising economic weight. In theory, China could use its economic leverage to encourage cooperation between Kurdish authorities and central governments. Through what might be termed developmental diplomacy, it even could frame economic integration as a shared interest, sidestepping the politically explosive issue of autonomy. This strategy stands within China’s BRI vision of creating trade stability through connectivity. This is a strategic vision that requires soft policy in the resource-rich Kurdish regions linking Central Asia, Iran, and the Mediterranean.

As both a NATO member and a central BRI partner, Turkey is essential to China’s Eurasian trade corridor. Yet Turkey’s aggressive stance against Kurdish autonomy, domestically and across Syria and Iraq, severely limits China’s portability.

However, China’s use of terminology around economic peacebuilding faces serious structural limits. Unlike Western powers, China lacks a tradition of conflict mediation grounded in political conditionality. Its refusal to engage normative questions, such as human rights and ethnic repression, makes China sustain relations with authoritarian regimes that perpetuate Kurdish marginalization. In practice, China’s commitment to non-interference shields it from responsibility but also from influence.

Among regional powers, Turkey poses the most acute dilemma. As both a NATO member and a central BRI partner, Turkey is essential to China’s Eurasian trade corridor. Yet Turkey’s aggressive stance against Kurdish autonomy, domestically and across Syria and Iraq, severely limits China’s portability. Any gesture interpreted as sympathy toward Kurdish self-rule could strain the Turkey-China relationship and jeopardize China’s strategic access to the Middle Corridor.

Iran presents a similar paradox. On one hand, bound by a twenty-five-year cooperation agreement worth billions of dollars, Iran is a vital partner in energy and transit networks. On the other hand, Iran’s hostility to Kurdish dissent leaves China complicit through silence. Moreover, China’s refusal to criticize Iran’s repression reaffirms its prioritization of regime relations over human rights, illustrating how sovereignty functions as a moral shield for realpolitik.

The Arab monarchies of the Gulf add another layer of complexity. They are eager to attract Chinese capital; they share its dislike to ethnically or politically pluralistic movements that might inspire domestic challenges. Their economic alignment with China, therefore, reinforces a regional consensus against Kurdish self-determination. For China, maintaining neutrality among these actors means accepting their red lines, which is a position that marginalizes Kurdish aspirations by default.

Any visible Chinese role in Kurdish territories would almost certainly be framed as a strategic advance, not a humanitarian concern

In addition to the above, China’s cautious approach must also be read against the backdrop of declining Western engagement. The U.S. and the EU retain military and political leverage over Kurdish affairs, the U.S. alliance with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) being the clearest case. However, its strategic retrenchment leaves a power vacuum that China could, at least economically, fill. Nevertheless, this shift is ambiguous. Any visible Chinese role in Kurdish territories would almost certainly be framed as a strategic advance, not a humanitarian concern. The resulting great power rivalry could further entangle Kurdish politics within the logic of global competition, rather than local emancipation. China’s avoidance of military intervention guarantees that its influence will remain largely indirect and transactional.

Thus, China’s engagement with the Kurdish question is therefore characterized by pragmatic restraint. Its policies in Iraq, Syria, and Iran remain driven by resource security, connectivity, and regional stability. From a realist perspective, China’s disinterest in Kurdish nationalism is entirely rational. China believes that supporting the Kurds would alienate key state partners, while ignoring them costs little politically. Nevertheless, the long-term course of China’s Middle East presence could unintentionally empower Kurdish regions. Infrastructure development, digital connectivity, and energy cooperation might gradually integrate Kurdish territories into broader economic networks, fostering interdependence that reduces conflict incentives. In this sense, China’s “soft game” lies not in overt diplomacy but in the structural transformations that accompany economic globalization.

Without addressing the Kurds’ historical grievances and the authoritarianism of regional states, development risks entrenching inequality rather than resolving conflict.

Yet, this optimistic reading must be tempered by cynicism. Economic integration does not automatically translate into political reconciliation. Without addressing the Kurds’ historical grievances and the authoritarianism of regional states, development risks entrenching inequality rather than resolving conflict. Thus, China’s insistence on neutrality becomes complicit in maintaining an unjust status quo. In the evolving multipolar system, China’s approach to the Kurdish question encapsulates its broader foreign policy dilemma. For China, the question is how to reconcile principled non-interference with growing strategic responsibility. The Kurdish question, rooted in historical deprivation and geopolitical rivalry, cannot be solved through trade routes alone. Yet, as Western influence diminishes, China’s cautious engagement introduces a new form of power, one that operates through infrastructure, investment, and diplomacy rather than bombs and sanctions. Whether this “Soft Game” succeeds depends on China’s willingness to evolve from an economic stakeholder into a political stabilizer. So far, China’s position remains strategically based on avoiding risks: profitable but passive, principled but paralyzed. Nevertheless, its very existence changes the power calculus in the Middle East, suggesting that the Kurdish question may soon test China’s capacity to shape regional order without repeating the failures of Western imperialism.

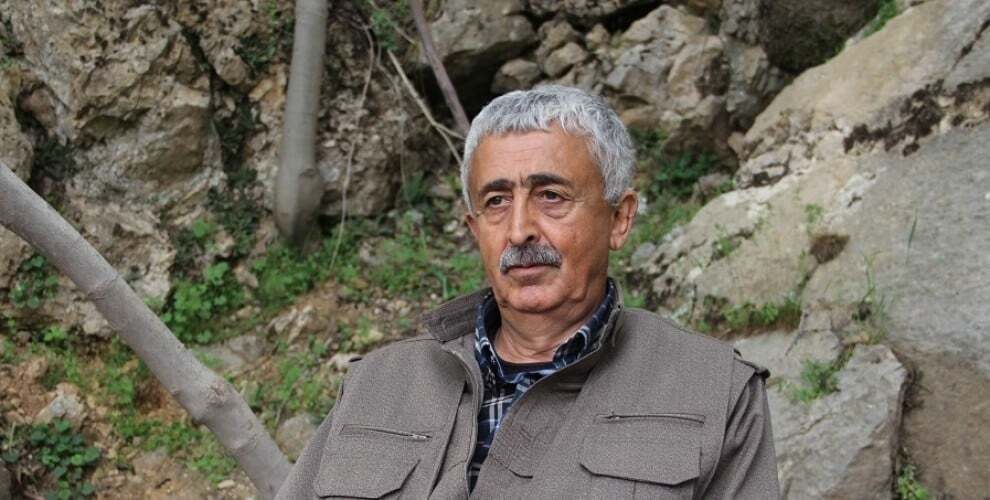

Seevan Saeed

Seevan Saeed is an Associate Professor in Area Studies at Shaanxi Normal University, China and Lecturer at Rojava University, Syria. He received his BA degree in Sociology and MA in Social Policy at the University of Wolverhampton,UK. He gained a PhD in Middle East Politics at the University of Exeter in 2015. He has delivered lecturers in domestic and international universities since 2015. He published articles and papers in six languages on social and political issues in the Middle East and beyond.