From Missing Children to Geopolitical Blackmail: Turkey in the Epstein Files

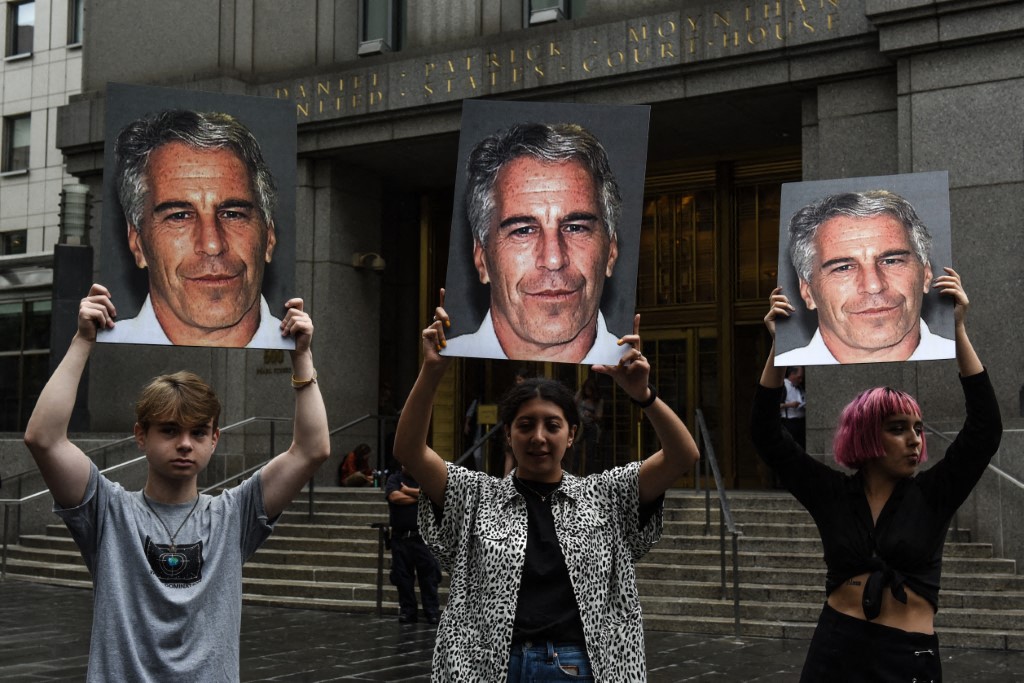

NEW YORK, NY – JULY 08: A protest group called “Hot Mess” hold up signs of Jeffrey Epstein in front of the Federal courthouse on July 8, 2019 in New York City. Stephanie Keith/Getty Images/AFP (Photo by STEPHANIE KEITH / GETTY IMAGES NORTH AMERICA / Getty Images via AFP)

The release of millions of documents related to Jeffrey Epstein by the US Department of Justice has generated significant attention in Turkey, as it has globally. In Turkey, however, the debate quickly moved away from speculation over “who might be implicated” in the Epstein files. Instead, it turned toward long-standing allegations of child abuse and human trafficking – issues that have been raised repeatedly for years but have never been examined comprehensively. The question at the centre of the discussion became not who might be exposed, but why such cases in Turkey so rarely lead to full investigations.

Rather than functioning as a disclosure, the Epstein files had a reflective effect in Turkey. They pushed the country to look inward, bringing unresolved domestic scandals back into focus and exposing a persistent inability, or unwillingness, to confront them seriously.

The released documents include the names of several business figures from Turkey. Among them are email correspondence from 2004 between Ghislaine Maxwell and Ahmet Mücahit Ören, the CEO of İhlas Holding; records in which the name of Fettah Tamince, the owner of Rixos Hotels, appears; and Mehmet Arda Beşkardeş, a US-based immigration lawyer of Turkish origin.

Opposition parties argue that the Turkish dimension of the Epstein files must be investigated transparently. Parliamentary questions submitted by lawmakers from the Republican People’s Party (CHP) have been pending on the agenda for an extended period without resolution.

Missing children and human trafficking

One of the main reasons the Epstein documents have resonated so strongly in Turkey is the long-standing lack of transparency around missing children and human trafficking. Official data is either not shared openly or is widely believed to understate the scale of the problem. Although Turkey’s official statistics agency reported that more than 100,000 missing children cases were filed between 2008 and 2016 – a figure unusually high by international standards when adjusted for population – regular and transparent data sharing stopped after 2016.

International reports describe Turkey as a transit country for human trafficking due to its geographic position. In identified cases, a significant proportion of victims are children, with sexual exploitation – particularly in tourist regions – frequently highlighted. Experts stress that official figures reflect only detected cases and that the actual scale of trafficking is likely far greater.

The release of the Epstein files also revived debates over missing children cases that emerged after the devastating February 6 earthquakes. While the Interior Ministry released different figures at different times, opposition parties and civil society groups warn that hundreds of missing children may never have entered official records.

Reports claiming that some children were transferred to institutions linked to religious sects and congregations after the earthquakes have never been conclusively examined, as parliamentary motions calling for an investigation were rejected.

A child abuse case implicating a former Dutch official and Turkey’s security establishment

Mehmet Korkmaz, a former Turkish police officer stated in a video … that underage boys were taken to Demmink during his visits to Istanbul.

For years, allegations have circulated that Joris Demmink, former Secretary-General of the Dutch Ministry of Justice, sexually abused children during official visits to Turkey in the 1990s. Demmink served as the highest-ranking civil servant in the ministry between 1993 and 2010. Eren Keskin, co-chair of the country’s Human Rights Association (İHD) and a prominent human rights lawyer, has publicly stated that testimonies alleging sexual abuse of children by Demmink during his trips to Turkey reached the association years ago, but were never effectively investigated by Turkish authorities. According to Dutch media reports, Turkey also refused to cooperate with inquiries conducted in the Netherlands.

Keskin has said that during Demmink’s visits to Turkey, he was allegedly protected by state officials, with security arrangements in place, and that testimonies point to the systematic sexual abuse of children. One such testimony comes from Mehmet Korkmaz, a former Turkish police officer, who stated in a video interview published in 2012 that underage boys were taken to Demmink during his visits to Istanbul.

Keskin also noted that the case file points to figures within the senior security bureaucracy of the period, including Mehmet Ağar. A central figure in what is often referred to as Turkey’s “deep state,” Ağar served as chief of police and later as interior minister during the notorious 1990s, a decade associated with the “dirty war” against the Kurdish movement. Individuals who say they were victimised by Demmink sought to bring legal action in the Netherlands, but Dutch prosecutors refused for years to open a full investigation. In Turkey, despite applications by Eren Keskin and human rights organisations, the case never developed into a comprehensive judicial inquiry.

The case was later brought before the US Helsinki Commission (CSCE). In testimony delivered on October 4, 2012, during a briefing titled ‘Listening to Victims of Child Sex Trafficking,’ Dutch criminal defence lawyer Adèle van der Plas, acting as legal counsel for two Turkish complainants, outlined the allegations against Demmink. According to van der Plas, the victims, identified as Mustafa Y. and Osman B., claim they were raped and sexually abused by Demmink in Turkey between 1995 and 1997, when they were 11 and 14 years old.

Van der Plas further alleged that instead of being investigated, the Demmink case was used by Turkish authorities as leverage to pressure the Netherlands over Kurdish activists. According to her testimony, this leverage resulted in a Kurdish defendant receiving a harsh sentence based on fabricated evidence, while the Demmink file was buried and Demmink himself shielded from accountability.

Unresolved child death at a Turkish resort linked to Epstein’s “masseuse training program” resurfaces

Documents released by the US Department of Justice include email records showing that individuals connected to Jeffrey Epstein were sent to the Rixos Premium Belek resort in Antalya in 2017. One of the names appearing in the correspondence is Lesley Groff, Epstein’s long-time assistant and senior employee. The emails describe plans for a female masseuse – or possibly several individuals – working at a private spa linked to Epstein to attend what was vaguely described as a ten-day “basic therapist training program” or internship at the Rixos hotel. The correspondence with Rixos representatives details requests for résumés, skill-level assessments, and payment arrangements.

The appearance of the Rixos name in the Epstein files has also revived public attention to a child death previously linked to the hotel chain. On September 9, 2011, 16-year-old Burak Oğraş, an intern at the Rixos Premium Tekirova hotel in Antalya, was found dead in an empty pool near the staff dormitories. The incident was initially recorded as a suicide, a conclusion the Oğraş family has consistently rejected, maintaining that their son was murdered.

Burak’s father, Murat Oğraş, has stated that shortly before his death, his son told his girlfriend that “there are perverts at the hotel,” that his mobile phone went missing on the night of the incident, and that evidence was tampered with. The family believes Burak was killed because he witnessed alleged sexual abuse at the hotel.

Another individual named in the Epstein documents is Mehmet Arda Beşkardeş, a Turkish-born immigration lawyer registered with the New York Bar. Records included in the JPMorgan case filings and in lawsuits involving the US Virgin Islands show frequent email, messaging, and financial transactions between Beşkardeş and Epstein. The documents indicate that Beşkardeş was involved in handling US entry procedures, visa applications, and financial paperwork for some of Epstein’s victims.

The Khashoggi case resurfaces through the Epstein files

The assassination of Jamal Khashoggi illustrates how an international crime committed in Turkey was treated less as a judicial matter than as a political and geopolitical instrument. Although the Khashoggi case has no direct legal connection to the Epstein files, it resurfaced in public debate after the release of Epstein-related correspondence referring to an Apple Watch in emails between Epstein and Miroslav Lajčák, the national security adviser to Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico.

“We gave the tapes. We gave them to Saudi Arabia. We gave them to America. We gave them to the Germans, the French, the British – everyone.”

Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi entered the Saudi consulate in Istanbul on October 2, 2018, to obtain documents required for his marriage and never emerged. It was subsequently established that he was killed inside the consulate by a team sent from Saudi Arabia.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan later said that Turkey had shared recordings obtained by Turkish intelligence with international actors. In a statement in November 2018, he said, “We gave the tapes. We gave them to Saudi Arabia. We gave them to America. We gave them to the Germans, the French, the British – everyone.”

More far-reaching claims also circulated among US journalists and in congressional circles. In 2019, an article published in Spectator US under the byline “Cockburn” alleged that Jared Kushner had given Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman a green light to detain Khashoggi; that Turkish intelligence intercepted that phone call between Kushner and bin Salman; and that President Erdoğan used this recording as leverage over US President Donald Trump. According to the same account, this pressure contributed to Trump’s decision in 2019 to withdraw US troops from northern Syria – a move that cleared the way for Turkey’s ‘Operation Peace Spring’ against Kurdish-held areas.

The most consequential name in Turkey’s Epstein context is not Turkish: Tom Barrack

Barrack’s ties to Epstein were extensive.

The most striking figure to emerge from the Epstein documents in connection with Turkey is not a Turkish businessperson or official, but Tom Barrack, the US ambassador to Ankara and US special envoy for Syria. Barrack’s ties to Epstein were extensive. Roughly 55 pages of largely redacted correspondence show Barrack in direct contact with Epstein within political circles closely aligned with Donald Trump, for whom Barrack served as a major fundraiser during the 2016 presidential campaign.

Barrack’s significance for Turkey, however, does not stem primarily from these communications but from his continuing influence in the region. In his public assessments of the Middle East, Barack has consistently framed the region not in terms of modern political systems or collective rights, but as a landscape defined by tribalism. Statements such as “There is no Middle East, only tribes and villages” and “benevolent monarchies work best” have fuelled criticism that he views the region’s populations not as equal political actors, but as communities to be managed.

This worldview has taken clearer shape in Barrack’s remarks on Syria’s future governance. In June 2025, he argued that Syria’s highly centralised system required “alternatives”, only to state later that year at the Doha Forum that “decentralisation has never really worked anywhere in this region,” explicitly rejecting federal or autonomous models. The apparent contradiction reinforced concerns that his vision allowed little space for pluralism or self-rule.

Barrack’s position translated directly onto the ground in his statements on the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), particularly as the Syrian transitional authorities launched a campaign in January targeting Kurdish neighbourhoods in Aleppo, a process that evolved into a broader push to dismantle the Kurdish-led autonomous administration in Rojava. Describing the SDF as a temporary and purely functional military formation, Barrack implied that Kurds should not be recognised as a permanent political actor in Syria’s future. This stance closely aligned with Turkey’s long-standing demand that the SDF be dissolved, and prompted criticism that the United States was abandoning its principal partner in the fight against ISIS, one that had suffered tens of thousands of casualties.

Barrack’s remarks triggered strong backlash from Kurdish political actors, regional experts, and minority representatives. Critics warned that once again, Kurds were being sidelined in the name of security and stability, and that politically erasing the SDF risked unleashing a new cycle of violence and instability in northeastern Syria.

Kamal Chomani

Editor-in-Chief of The Amargi and PhD candidate at Leipzig University