If peace talks fail in Turkey, racism will erupt

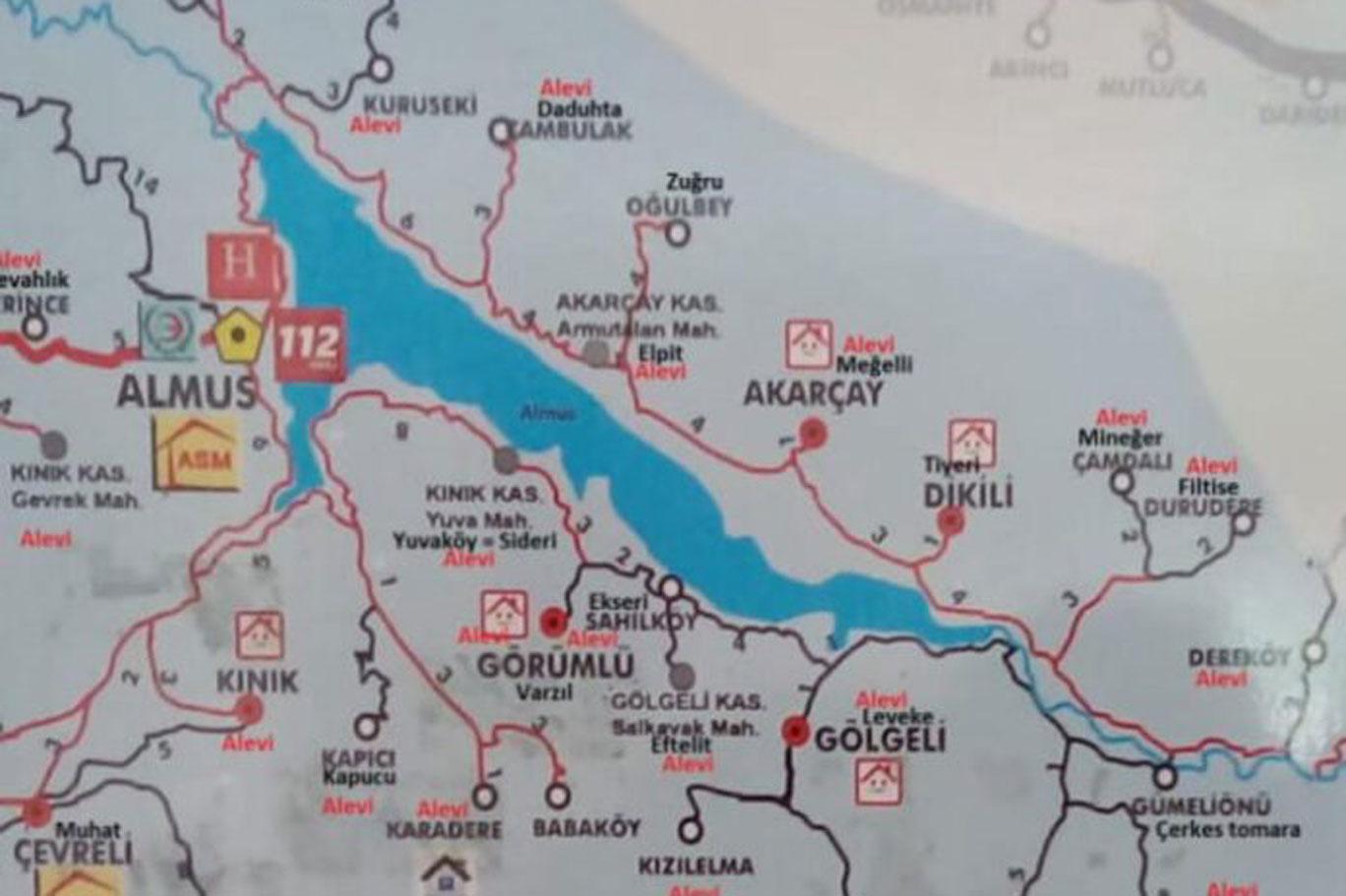

The villages marked with the word Alevi | Photo Credits: Anadolu’nun Sesi Tokat

The ongoing war between the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the Turkish state since 1984 has reached a historic turning point. Peace efforts that began in October 2024 are gradually gaining momentum with the PKK’s declaration of a ceasefire in March 2025, its dissolution in May, a symbolic weapons burning ceremony on 11 July, and the announcement of the withdrawal of all its militants to outside the borders of Turkey on 26 October.

Although the Kurdish movement complains that Turkey has not yet made any concrete arrangements in return for these steps, surprisingly, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), which openly opposed the peace process between 2013 and 2015, which ended in a terrible war, and has been anti-Kurdish for decades, is supporting the current peace efforts.

On the other hand, a new wave of racism appears to be rising in Turkey alongside the peace process. While nationalist parties and organizations outside the MHP openly oppose the peace process, anti-Kurdish, racist rhetoric is also becoming widespread.

The author of one of the first comprehensive academic studies on the social, psycho-social, and political foundations of new racism in Turkey, “The ‘Dirty’ Others of New Racism – Kurds, Alevis, Armenians”, Associate Professor Hatice Çoban Keneş of Munzur University in Dersim (Tunceli), explains to The Amargi what is in her view the biggest obstacle to the peace process: the spread of new racism in Turkey.

Discussions about “new racism” in Turkey are relatively recent. Your book can be considered one of the first academic works in this field. How does new racism differ from “old” racism?

Since the 1950s, almost no nation-state has retained racist regulations or rules in its laws or constitutions. Internationally, the prohibition of racism has also received general acceptance. However, racism has not disappeared; it has taken on a new form, particularly through hostility towards immigrants or foreigners. Since the 1970s, a form of racism has emerged that stereotypes immigrants’ cultural differences, lifestyles, clothing, and behavior, turning them into hate speech. This new form has been defined in academic studies in Western Europe, particularly by theorists such as Etienne Balibar, Pierre-André Taguieff, and Martin Barker, as a form of racism based on cultural discrimination.

So how does this racism work?

There are two forms of this racism, which focus on culture. The first is based on cultural hierarchy. That is, it claims that certain cultures are deficient or inadequate based on prejudices such as that certain groups are not “civilized enough,” “hardworking enough,” or “have fallen behind because they have too many children.” This perspective attributes people’s social position to their own lack of effort. The second argument is based on emphasizing cultural differences. Here, ideas such as “it is impossible for different cultures to coexist” come to the fore. This discourse presents multiculturalism as a threat. Thus, the new racism is a much more unrestricted, sinister, covert, and discursively operating phenomenon that focuses on all kinds of cultural differences rather than biological indicators such as skin color.

Is this racism more prevalent among the middle and upper classes?

The new racists do not belong to a specific class, gender, or identity. The approach to Syrian refugees in Turkey can encompass all segments of society, regardless of class, intellectual level, or even ideological position. Even those who call themselves leftists can resort to racist discourse against Syrians. We are talking about racism based on exclusionary language and discourse that can find a place for itself within different ideologies. It manifests itself most intensely through the heavy use of new communication tools such as social media.

How does the new racism differ from, say, that in South Africa or Nazi Germany?

It operates in a hidden and sinister way. For example, in the apartheid regime in South Africa, in Nazi Germany, or in the United States until the late 1960s, racism was enshrined in law. Who was “inferior” and who was “superior” was clearly stated in the constitution, in schools, in hospitals, on buses, in every area of life. Today, no country’s constitution contains such language. Racism no longer targets a specific race or phenotype, but any kind of “difference.” Appearance, culture, ethnicity, religion, even lifestyle… Anyone we dislike or find uncomfortable can easily be labelled as “inferior.” The new racism operates like a system with blurred boundaries but a powerful impact, capable of drawing anyone in at any moment.

So, is nationalism the ideology that carries this new racism?

Not just nationalism, actually; cultural differences and sexism are also incorporated into the new racism. New racism is produced more within everyday life, especially through the female body. For example, we often hear statements such as “Kurdish women constantly give birth,” “Relationships between men and women are flexible among Alevis,” and “Russian women cheat on their husbands in Turkey.” Such discriminatory discourse easily finds its way not only onto the streets but also into the media. If you want to map out “other identities” in Turkey, looking at the media and media discourse is sufficient.

Under what circumstances does the anti-Kurdish racist wave in Turkey rise or fall? Are anti-Kurdish discourse or attacks actually under state control, or do they occur despite the state?

Racism in Turkey rises and falls according to cyclical fluctuations. Looking at it periodically, we can see that the “others” frequently change. Sometimes, leftists, communists, Armenians, Greeks, or different social groups become the target. However, the group that has been targeted by this hatred in the most persistent and structural way is the Kurds. Anti-Kurdish racism is not a temporary political atmosphere, but a historical phenomenon ingrained in the deep structure of the state, the bureaucracy, and society. Therefore, it is not merely anger that flares up during certain periods, but a habit that can be constantly reproduced.

In the past, the existence of Kurds was denied. So, does the acceptance of the existence of Kurds open another area of discrimination?

Now they don’t say “there are no Kurds”; instead, they say “they are separatists, they cannot adapt to the city, they have too many children, they are backward.” So, the new racism excludes by acknowledging rather than denying. This makes racism even more dangerous. Because racism feeds on images, not reality, fantasies such as “Kurds are terrorists in the mountains at night and in their homes during the day” become embedded in the social consciousness and are easily triggered during every crisis. This wave is neither entirely under state control nor independent of it. The state’s discourse, the language of the media, and the culture of impunity feed this racism. It is a system that is structurally sanctioned, unpunished, and even indirectly encouraged at times. Therefore, attacking Kurds has become a reflex. In moments of anger, crisis, or fear, the first target is always the Kurds.

However, when we look at racist discourse on social media, we see that the codes of old racism are also being used.

Of course, we are faced with a form of racism that builds on old racism but also goes beyond it. This is a form of racism that can be flexible in the face of reactions, that can create areas of escape from punishment, and that abuses concepts such as freedom of expression and humor. For example, let us recall the words reflexively uttered by a television presenter during a live broadcast in response to news of the 7.2 magnitude earthquake that struck Van, predominantly inhabited by Kurds, in 2011: “Even though the earthquake was in Van, it shook us all deeply!” When reactions came, defenses such as “I misspoke,” “I was misunderstood,” and “It was taken out of context” immediately kicked in. Most of these hurtful, discriminatory statements do not carry any criminal consequences.

I think a similar practice of impunity is being displayed regarding hate speech against Alevis.

Yes, in 2021, when a doctor in Tokat marked Alevi villages on a map and shared it, an investigation was launched against him, but the doctor defended himself by saying, “I wanted to locate my patients’ villages.” However, since there is no treatment method specific to Alevis, this was clearly an act of hate. The most difficult aspect of combating this new racism is precisely this. Because this racism operates alongside absolute denial. Statements that begin with “I’m not racist, but…” both legitimize racism and turn criticism around, creating a space for manipulation by saying, “If you interpret my words as racist, it shows that you are the racist.” Thus, racist discourse is not only concealed, but it also transforms into a defense mechanism that justifies itself.

If racist speech is not punished, are racist attacks also going unpunished?

Physical attacks are punishable regardless of whether they are racially motivated or not. For example, on 16 December 2018, in Sakarya, a Kurdish father and son were shot by Hikmet Usta, who said, “I don’t like you,” simply because they spoke Kurdish. The father, Kadir Sakçı, lost his life, and his son, Burhan Sakçı, was seriously injured. Hikmet Usta was sentenced to life imprisonment for this attack. However, the truth that the attacks were motivated by racism is often obscured by excuses such as “hostility” or “provocation.” This hides the racist motive. On the other hand, the impunity of racist speech triggers racist attacks.

Is there a law prohibiting racism in Turkey?

Yes, there is. Article 3 of Law No. 6701 states: “Discrimination based on gender, race, color, language, religion, belief, sect, philosophical and political opinion, ethnic origin, wealth, birth, marital status, health status, disability, and age is prohibited.” However, discrimination usually refers to de facto discrimination, and speech is excluded from this. On the other hand, the only identities that are truly protected among those mentioned in the law are Turkishness and the Sunni Islamic faith.

What do you mean?

The way racist or discriminatory speech is punished in Turkey is quite selective. Hate speech directed at Alevis, Kurds, Armenians, or LGBTI+ people often goes unpunished, while similar statements directed at Turks or Sunnis are punished much more severely. This clearly shows to whom the law and social conscience are ‘sensitive’ and to whom they are ‘deaf’. For example, in Dêrsim, where Kurds and Alevis live in large numbers, racist comments such as “that place belongs to pigs anyway” under a news story about wild boars coming down to the city are not subject to any sanctions. However, if you were to say the same thing about a city with a Turkish majority, you would immediately face legal action. This double standard shows that racism is reproduced not only in social but also in institutional forms.

Now, there is an ongoing peace process supported by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and its nationalist partner, MHP. However, anti-Kurdish racist parties openly oppose this process. Looking at Turkey at this level, what kind of polarization do you see politically?

From 2015 until October 2024, the AKP-MHP alliance systematically carried out anti-Kurdish policies under the guise of fighting the PKK. The MHP, which in the past even denied the existence of Kurds, suddenly shifted to a “we must make peace with the Kurds” policy in response to developments in the Middle East. However, this did not eliminate anti-Kurdish sentiment. On the contrary, racism in Turkey changed parties and began to target the ruling party as well. We observe that the discourse of peace that came after years of Turkish nationalist-militarist rhetoric and anti-Kurdish practices has further intensified and provoked anti-Kurdish racism in Turkey.

How is racism increasing while the AKP-MHP government uses the discourse of peace?

The bases of the AKP and MHP may not appear to be in an “anti-peace” position in the current context. These bases may not be dramatically shifting to racist parties opposed to the government at this stage. However, if the peace talks fail, anti-Kurdish racism could explode in Turkey. In other words, the anti-Kurdish sentiment that the AKP and MHP bases have suppressed over the past year could join forces with anti-peace groups and have a devastating impact. Let us not forget that the failure of the peace talks with the PKK between 2013 and 2015 led to a decade of serious conflict and destruction.

So how would the success of this process, i.e., the establishment of peace between the political power and the Kurdish movement, affect anti-Kurdish segments?

Since the tendency to obey the leader is very strong among the AKP and MHP bases, I don’t think there will be serious objections from the ruling party’s base. Likewise, there may not be serious opposition from those who pledge allegiance not to the government but to the state. If various legal and political reforms are implemented quickly to make peace permanent, racist reactions opposed to peace may also become marginalized over time. However, this will not mean the end of racism in Turkey. When Kurds cease to be the “other,” other others will be found. For example, Syrian refugees become the new “others,” and racism shifts its focus there, attempting to become dominant in politics. Reducing racism and hate speech requires a much more comprehensive systemic change. Turkey appears to be far from achieving this.

We constantly talk about “racists,” “racist discourse,” and “racist groups,” but can you provide a clear address for these?

We cannot reduce new racism to a single, homogeneous identity or ideology. In Turkey, any social democrat who says “Turks and Kurds are brothers,” even those who define themselves as “anti-racist, socialist,” can easily resort to racist rhetoric against Syrian migrants. That is why the new racism is much more ambiguous than the old racism; it has much more room for escape, and is therefore much more dangerous. Moreover, this racism has the potential to go beyond mere rhetoric and lead to actual attacks and lynchings. There is currently a very large segment of society rubbing their hands in anticipation of the failure of the peace process with the Kurds.

Is it right to call all of them racist?

Of course not. Many groups oppressed by the government believe that peace with the Kurds will strengthen the government. Therefore, if the peace process ends in failure, they may tend to direct their anger at the government towards the Kurds or the Kurdish movement. Attacking the Kurds in Turkey has become almost a reflex. Therefore, when everyone looks for an address to direct their anger, they resort to the easy option of settling the score with the Kurds first.

How do Kurds who are subjected to racism react?

Kurds are not immune to hate speech directed at LGBTI+ people and Syrian refugees. We see that discriminatory language against different identities has begun to be used among Kurds as well. Groups constantly exposed to racism are now beginning to express their own problems and issues by leaning on racist rhetoric. An inclusive, democratic language or multicultural perspective against racism is perceived as a weakness, as turning the other cheek to the slap.

Why is this the case?

This requires a psychoanalytic analysis. We must deeply discuss what deficiencies in ourselves are covering up the characteristics we attribute to the other. This requires a social confrontation. The logic is: “While the other disrupts my sense of wholeness and integrity, I must develop the same discourse or action against them so that justice is served.” Such responses can spread in concentric circles which is very dangerous. Furthermore, the otherized may seek to satisfy their sense of “wholeness” by otherizing those seen as weaker than themselves, rather than addressing those who otherize them. Kurds’ resorting to discriminatory discourse against Syrian migrants can be explained somewhat in this way.

Turkey has been facing a serious economic crisis for some time now. With the middle class virtually collapsed, unemployment deepening, and anxiety about the future increasing, do these conditions have a decisive impact on the wave of racism?

Of course, the economic crisis, poverty, and the feeling of not getting what one deserves directly fuel racism. In the interviews for my doctoral thesis, I saw this feeling of “racist jealousy” very clearly. One participant began by saying, “I had a Kurdish friend who went to the same school as me,” and then continued: “Kurds are not what they seem. My friend didn’t wash his hands after using the toilet. Over time, we couldn’t get along and we parted ways. Then, one day I found out he had gotten married, had children, and got a government job! I was furious.” This example actually says a lot. Unable to explain their own failure or deprivation, they take out their anger not on the individual but on their identity. Thus, personal disappointment turns into social prejudice. This logic always works the same way, starting from individual experience and generalizing to all Kurds, Alevis, Syrians, and LGBTI+ people. Statements like “Unemployment has increased because of the Syrians, the economy is bad because of the Kurds; they smuggle, they take our jobs” are a reflection of this. As the economy worsens, anger shifts from being class-based and political to being identity-based, and the system is no longer the culprit—it’s the “other.”

So how can this be prevented?

People cannot react against the rulers because there is an anti-democratic, authoritarian regime in Turkey. A man is oppressed by his boss at work, forced to work in slave-like conditions, but he directs the anger and violence towards his wife and children at home. He says, “Rent prices have increased because of the Syrians,” and spreads hatred towards Syrians. People do not take a critical approach to landlords who see Syrian refugees as an opportunity and raise rents. When people see the real source of their problems and react to it, they can stop seeing the weakest links as victims. And of course, unless structural reforms are made and racism is punished, it will become even more widespread.

İrfan Aktan

İrfan Aktan was born in Hakkari-Yüksekova. He graduated from the Journalism Department of the Faculty of Communication at Ankara University in 2000 and completed his Master’s Degree in the Women’s Studies Center at Ankara University. He worked as journalist for Bianet, BirGün newspaper, Express, Nokta, Yeni Aktüel, and Newsweek-Türkiye magazines, Gazete Duvar, Artı Gerçek and IMC TV. His books include Nazê/Bir ‘Göçüş’ Öyküsü, Zehir ve Panzehir: Kürt Sorunu and Karihōmen: Japonya’da Kürt Olmak.