Kurdish Theatre in Istanbul: a Stage for Memory, Language, and Resistance

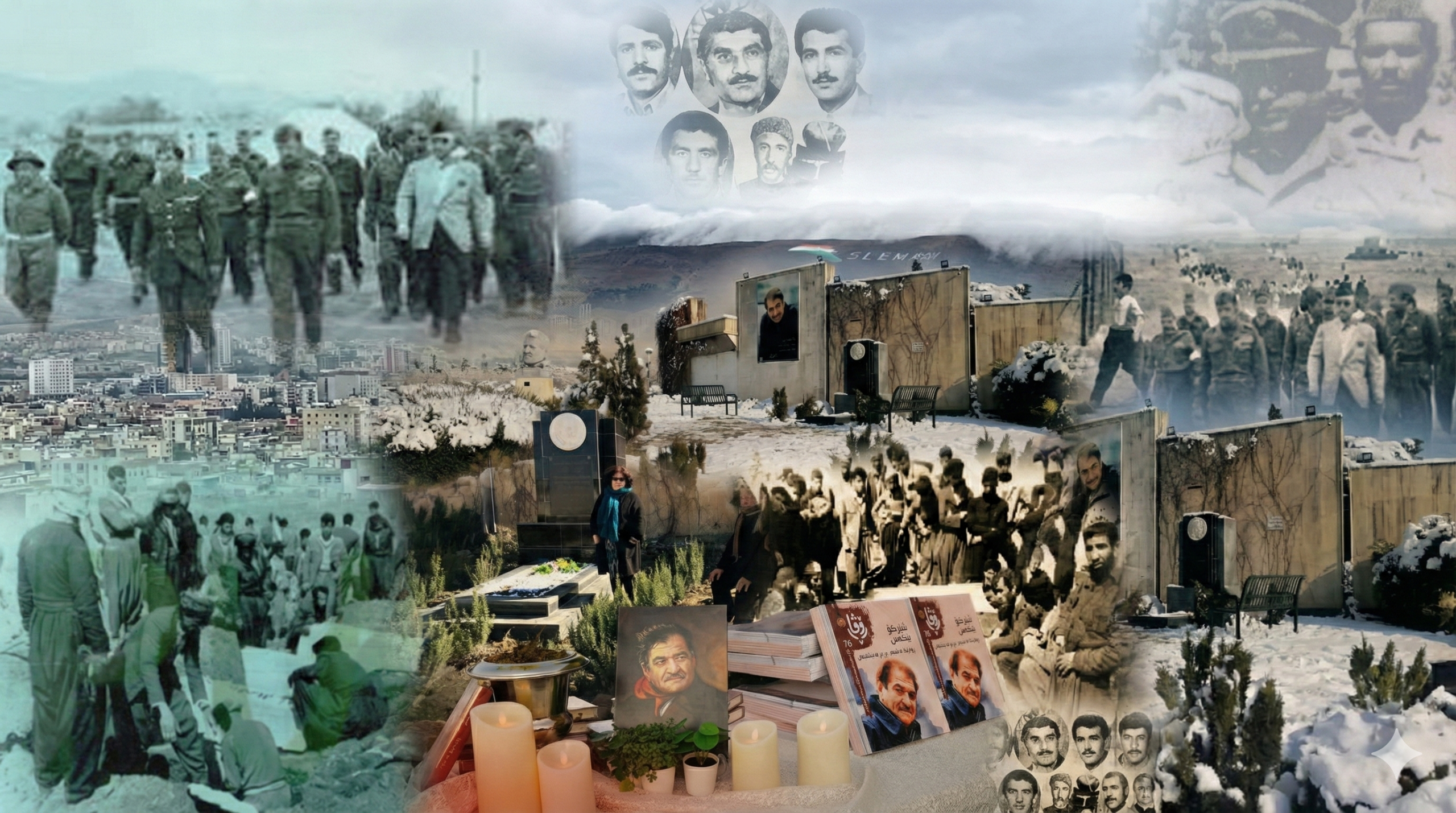

A photo from the Kurds New Year’s celebration on 13 January 2025 | Pictuer Credits: Instagram Page of Janya TV

Istanbul, due to its large Kurdish population, is a major center for Kurdish-language theatre. For years, artist groups have propped up powerful spaces of expression and self-discovery for Kurds in the city, using storytelling to turn the stage into a place of resistance against decades of state repression. But with performances relying on volunteers and individuals’ efforts, dramatist Avaşin Yorulmaz says institutional and financial support is necessary to continue developing Kurdish theater and protect Kurdish performing arts.

From Home Stories to the Stage

When Kurds talk about theater, the conversation often turns to stories told at home, especially tales from the mouths of mothers and grandmothers, mimicry, and reenactments of daily events. For Kurds, theatre is not limited to the stage but is part of everyday life.

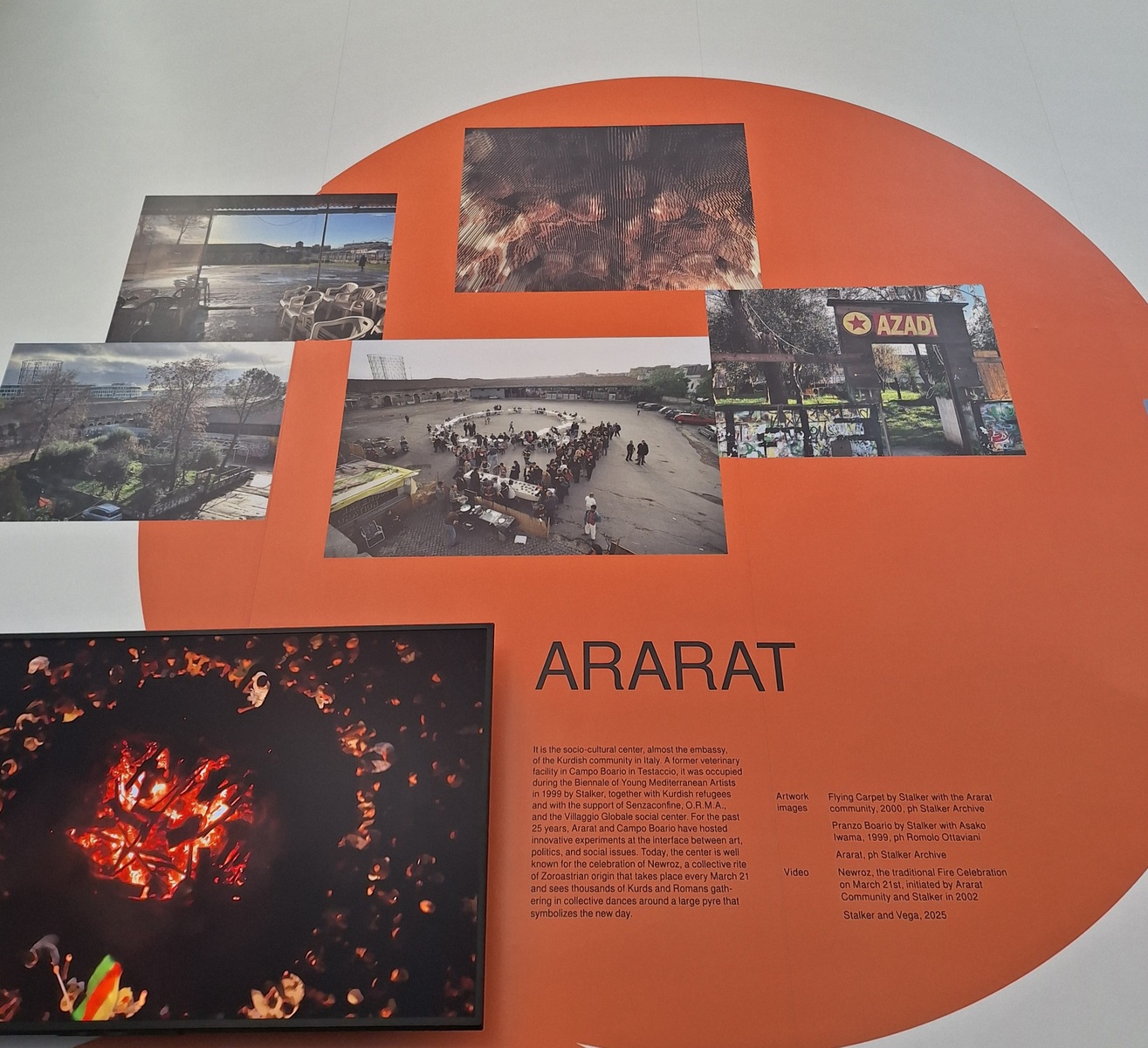

Avaşin Yorulmaz works at the Istanbul Theatre Workshop (İSTA) group – affiliated with the Kadıköy Art Center – and produces works in the field of Kurdish theater. He says, for him, the biggest factor in turning to theater was his grandmother: “I grew up listening to my grandmother’s tales every night. I learned from her how to tell stories – not exactly as they are, but by adding bits of yourself, to turn them into stories.” He added that Kurdish sketches were performed not only in homes but also at weddings and New Year’s and Newroz celebrations, pointing out that these social aspects are quintessential parts of Kurdish performance traditions.

Avaşin’s words relay the strong connection between Kurdish theatre and Kurdistan’s oral traditions. For many like him, the stage is a space where the mother tongue comes back to life, and the heritage of inherited memory can continue its centuries-long march through generations.

Dengbêjî, Çîrokbêjî, and Bizarî: Traditional Forms of Theatre

Like many societies, Kurds have different traditional forms of theatre, with dengbêjî, çîrokbêjî, and bizarî being among the main ones. Avaşin explained that the styles of çîrokbêjî (storytelling) is more based on everyday stories, while dengbêjî narrates Kurdish uprisings and political memory through kilams (bards’ musical epics and folktales) and plays an important role in sustaining Kurdish national consciousness.

He described the third type, bizarî, as satirical and mimicry performances: “It has two forms: bizarî and biqayde. Bizarî focuses on verbal mimicry, while biqayde is based on physical mimicry. They can be used separately or in combination.”

With the rise of armed resistance by Kurdish guerrilla movements, bizarî, not needing to rely on written texts, became a forum for political commentary; and because people were already familiar with the form, they quickly embraced the new political content.

The Turkish state placed innumerable restrictions on Kurdish theater in the 1990s

Guerrilla Theatre emerged during this period, with guerrilla fighters and local supporters performing small sketches together in villages, sometimes as a form of performed propaganda. One lesser-known play that he mentioned, Mixtaro, about local village leaders served this very purpose: “It criticized the practice of turning village leaders into informants [for the Turkish state].”

Kurdish Theatre in the Public Sphere

The Turkish state placed innumerable restrictions on Kurdish theater in the 1990s, in order to block it from spreading beyond homes and villages and becoming more visible in public spaces. Despite this, the establishment of Amed City Theatre in 1990, the Mezopotamya Cultural Center in Istanbul in 1991, and Teatra Jiyana Nû in 1992, along with many other independent groups, became important turning points for Kurdish theatre on the public stage. This period shaped Kurdish theatre’s presence not only in the cultural field but also in the political.

Bans on the Kurdish language, the prohibition of Kurdish plays, the closure of theatre groups, and the prevention of performances followed. Still, Kurdish theatre continued to produce work. Even as state-appointed trustees shut down Kurdish-language theatres in the cities, artists and audiences would not relent.

Avaşin sees this as one of the strongest moments of resistance for Kurdish theater: “People continued Kurdish productions without expecting any financial gain. Some friends would work in construction or other jobs, and when they were done, they would come to rehearse and perform.”

This legacy of resistance is clear to see in Istanbul, where the city has remained an important center for Kurdish performing arts: Kurdish plays staged in small halls, independent theatres, or temporary venues show both the dedication that has allowed continuity and the strong audience demand that yearns for it. But the lack of systematic and sustainable institutional structures often creates challenges.

The absence of structures means that production mostly continues through personal effort: “For this to be sustainable, institutional support is necessary. We need institutions that can train actors, directors, writers, decorators, lighting designers, and dramaturgs,” Avaşin said.

He emphasized that these shortcomings are not the result of individual will, but political constraints, emphasizing that pressure on the Kurdish language also affects institutionalization in arts and culture. Creating space for cultural production and strengthening Kurdish theatre are closely tied to the political climate.

As a result, despite an increase in Kurdish theatre productions and Kurdish-language texts in Istanbul, finding actors who speak Kurdish and building enduring artistic institutions remain major challenges.

A Theatre That Lives with Its Audience

Rooted in oral tradition and extending to the modern stage, Kurdish theatre is not only an artistic practice but a collective space that platforms language, memory, and resistance.

“Audience members see themselves on the stage.”

Kurdish-language plays staged in Istanbul and other major cities make silenced stories visible and allow Kurds to reclaim their mother tongue in public spaces. This has led to what Avaşin described as one of the strongest aspects of Kurdish theatre: the relationship with its audience, “Audience members see themselves on the stage. The hall would be full every week we stage Kurdish plays. So, there is no problem with attracting audiences. People are genuinely interested in Kurdish theatre.”

And he noted that this interest is not limited to Kurdish speakers: “People who don’t speak Kurdish also come. Some come for emotional reasons, some out of curiosity.”

Rather than just being a relic of past traditions, it is a living and breathing field…

Instead of retreating under pressure, Kurdish theater in Turkey and North Kurdistan stands out as efforts to rebuild Kurdish identity in the public space. Rather than just being a relic of past traditions, it is a living and breathing field, deeply connected to today’s political, social, and cultural struggles and the people’s will to resist erasure.

Avaşin, who completed his undergraduate and graduate studies in performing arts, continues his work with the Istanbul Theatre Workshop group, aiming to create an alternative space for production and transmission in Kurdish theatre. He also works with dengbêjî as an independent performing artist and performs shows in different cities.

Şilan Bingöl

Şilan Bingöl is an independent researcher who studied sociology at Galatasaray University and Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon. Her master's thesis is on media sociology.