Roots of Iran’s 1979 Revolution

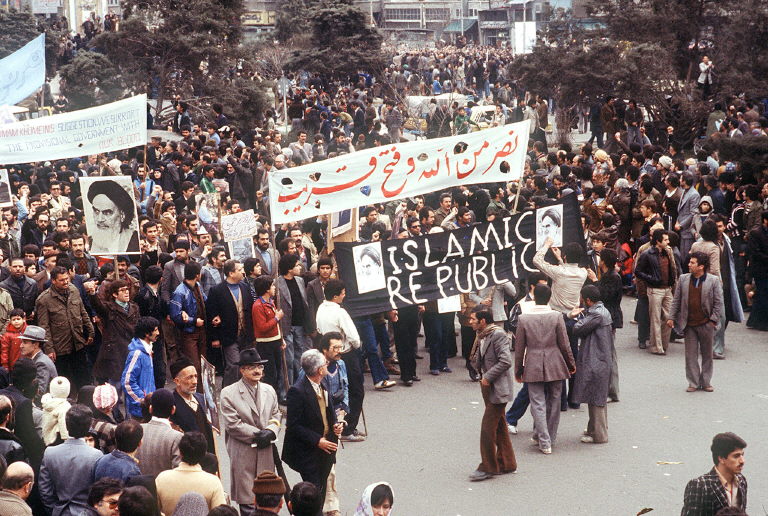

Photo taken in Tehran in February 1979 of a demonstration in support of the National Front government formed on 14 February by Ayatollah Khomeini.(Photo by GABRIEL DUVAL / AFP)

Iran is marking the 47th anniversary of the 1979 Revolution, but this year’s commemoration is far from celebratory, as the Islamic Regime has responded to country-wide protests with unrelenting violence. Fireworks on the day of the anniversary in Tehran were met with chants of “Death to the dictator!” and “Death to Khamenei!”

These voices signal a persistent and deepening rage toward a system many Iranians hold responsible for unprecedented poverty, lethal state violence, environmental devastation, and institutionalized gender apartheid. Nearly five decades after the revolution that established this political order, it is worth looking at how the revolution emerged, and the structural, social, and political forces that made it possible.

Uneven Development

The nationalization of Iran’s oil industry under Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in the early 1950s set the stage for dramatic political and economic change. When Mossadegh was overthrown in the 1953 coup, the disruption gave Mohammad Reza Pahlavi greater control over oil revenues, supplying the funds for his ambitious modernization push. The Shah’s White Revolution and the Third Five-Year Development Plan drove industrialization, infrastructure expansion, and social reforms.

A cornerstone of the White Revolution was land reform, which was designed to weaken major landlords and redistribute farmland to peasants while boosting agricultural productivity and agri-business. In practice, however, many peasants received plots too small to sustain their families, pushing them into debt, wage labor, or migration. Landlords were compensated with state bonds or shares in new enterprises, which pacified them politically even as they lost direct control over the land.

Excluded from most new industrial opportunities but still embedded in local social networks, many traditional elites retained enough influence to challenge the regime when political openings emerged.

The White Revolution’s social reforms also unsettled the Shia clergy. Extending suffrage to women and expanding secular education weakened clerical authority. The growth of secular courts curtailed the judicial control of the ulama – influential Muslim scholars – while land reform dissolved economic structures sustaining religious endowments. These policies collectively threatened the clergy’s power base and social prestige.

Among their most outspoken critics was Ruhollah Khomeini, who denounced the Shah’s policies as un-Islamic and who, after his exile in 1964, built an ideological network abroad that fused Islamic principles with revolutionary rhetoric – an alliance of faith and political mobilization that would later prove decisive.

Authoritative Modernization and the Rise of Social Tensions

Industrial expansion, literacy campaigns, healthcare improvements, and access to higher education created a growing urban middle class. At the same time, these reforms deepened social and economic divides by favoring urban elites, bureaucrats, and industrialists with oil-funded growth. All the while rural peasants were forced into poverty and displacement. The result was a 15% increase in the proportion living in the urban sector due to local migration between 1956 and 1976.

The pattern of investments also showed preferential treatment based on long-existing divisions within Iran: around 40% of major manufacturing establishments were concentrated in central provinces such as Tehran, Isfahan and Tabriz. Government expenditure in Central Provinces, Isfahan, Yazd, Azerbaijan was between 10-20%, while for Kurdistan, Kerman, Sistan and Hamedan it was only between 1-5%. As traditional village leaders and networks collapsed, massive migration swelled cities like Tehran with underemployed migrants living in slums, lacking infrastructure or social ties.

The huge increase in oil revenues in the 1970s, and the government’s decision to rapidly spend these earnings domestically, fueled high inflation in Iran, which eroded purchasing power of the majority. And, similar to corruption in Iran today, more and more, the benefits of economic growth were perceived to be concentrated among the elite and those connected to the regime.

State-led reforms also targeted women’s rights, and some improvements were clear to see, particularly in urban centers. Women were granted the right to vote and run for office in 1963, and access to education and employment increased. The Family Protection Law restricted polygamy, raised age of marriage to 18, and enhanced divorce and custody rights for women. However, these advances remained limited, as women’s participation in leadership roles stayed extremely low, operating within male-dominated institutions. Additionally, non-Persian women benefited very little, as Persian nationalism superseded all reforms. And these top-down policies likewise did not benefit women of lower socio-economic tiers or rural women who were struggling with other structural factors such as economic disparities, lack of awareness, and lack of access to legal services.

Overall, women experienced greater social and legal freedoms but faced strict political repression and constraints on genuine empowerment.

These reforms were influential in social and economic life, but failed to offer the opportunity for political participation. The Shah tightly controlled political parties, labor unions, and civic institutions. Ordinary citizens could gain an education, work in modern industries, and access new social services, but they remained largely excluded from decisions affecting the country’s direction.

Many segments of society – particularly rural migrants, slum dwellers, and the urban poor – remained unheard. A new type of citizen was created: socially modernized but politically limited, a combination particularly receptive to revolutionary ideas.

Ideology, International Pressure, and the Road to Revolution

The Cold War cast a long shadow over Shah’s reign, who saw himself as the West’s frontline defense against communism.

Iranian authorities treated leftist movements, trade unions, and student organizations as potential Soviet proxies. SAVAK, the Shah’s notorious secret police, surveilled and tortured thousands suspected of leftist sympathies. By silencing moderate reformers alongside radicals, the regime destroyed any middle ground where peaceful opposition might have formed, pushing dissent toward more ideological and religious channels.

In this environment, Islamic and intellectual opposition quietly consolidated power. Thinkers such as Ali Shari’ati fused Shia symbolism with anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist language, offering a vocabulary that deeply resonated with a society suffocated by dictatorship and Western dependency. His ideas transformed Islam into a moral and political critique of authoritarianism and foreign domination, bridging the gap between secular revolutionaries and the devout. His writings complemented Khomeini’s religious authority, forming a potent alliance that could mobilize across class and ideology.

By the late 1970s, U.S. President Jimmy Carter’s human-rights agenda pressured Iran to introduce limited liberalization. The Shah, caught between U.S. reformist expectations and his long-cultivated fear of leftist revolution, found himself politically paralyzed. Intended to modernize the monarchy’s image abroad, the gestures towards political freedoms instead exposed fragility at home.

The 1979 revolution was deeply rooted in decades of uneven modernization, political exclusion, and global entanglement. The Shah’s project of rapid development under American protection created a population that was more educated, urban, and socially conscious than ever, but also, more politically voiceless. Institutions that could have mediated between people and power had been dismantled, leaving the mosque, the street, and exile as the only remaining arenas of expression, ensuring that dissent, once ignited, spread uncontrollably.

Mahtab Mahboub

Mahtab Mahboub is an Iranian feminist activist and PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology at the University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany. Her research focuses on the intersection of gender and migration within the Iranian diaspora in Germany, with particular interest in narrative research, intersectionality, identity, and decolonial feminist theory. She also writes on social movements and political developments in Iran.