Syria: The Two-Phase Bloodbath of Suwayda

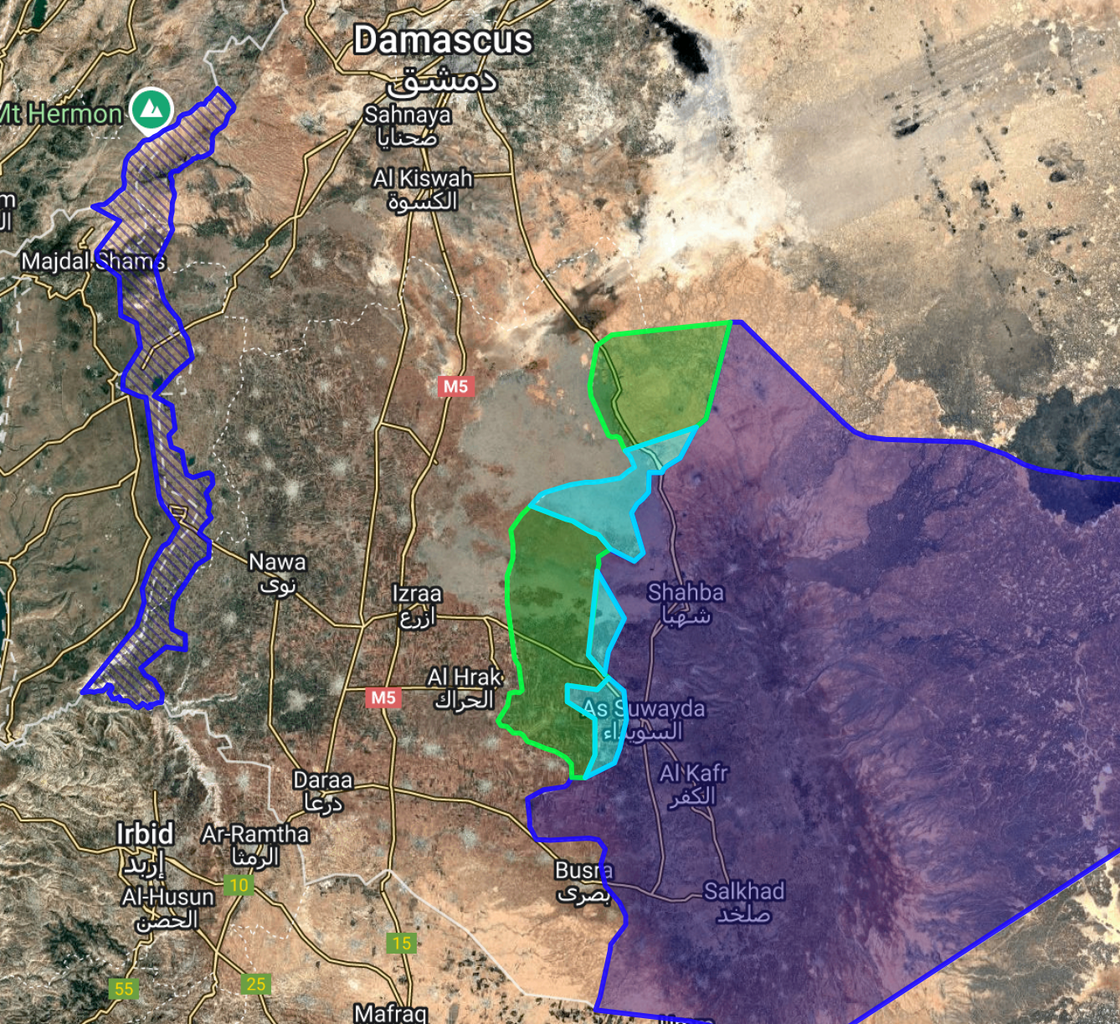

The image depicts, according to a compilation of sources, the map of the Bedouin-Syrian invasion of the Suwayda district as of July 18, 2025 | Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons

From July 13 to 23, 2025, the region of Suwayda in southern Syria was subjected to a violent attack by an informal alliance of government forces and tribal armed factions from several parts of Syria. This aggression constituted the second phase of a strategy to disarm the Druze community’s self-defense factions.

Media coverage, which was largely favorable to the government of Syrian interim president Ahmed al-Sharaa, echoed the official narrative, presenting the government forces’ intervention as a response to intercommunal violence between the Bedouin community of Suwayda and “outlaw Druze gangs” involved in “ethnic cleansing” of their Bedouin neighbors. The reality, however, is far less binary.

The image depicts, according to a compilation of sources, the map of the Bedouin-Syrian invasion of the As-Suwayda district as of July 18, 2025.

At the end of April, a Druze sheikh was falsely accused of insulting the Prophet Muhammad, and despite an official denial from the government, a pogrom against Druze and other “kuffar” (infidels) was initiated by Salafist students at the university in Homs. This led to armed clashes the day after in the Druze-majority city of Jaramana. The Druze factions were then accused of attacking members of the General Security, even though consistent reports suggested that tribal armed groups had initiated the assault on the city from its eastern entrance. This escalation quickly turned into an armed confrontation in the three main Druze-majority cities of the Damascus region, Jaramana, Sehnaya, and Ashrafiyyeh-Sehnaya, in which non-identified fighters and informal Islamist groups participated, some of whom had previously been recruited by the government forces. During the clashes, around forty Druze fighters from SUWAYDA attempted to come to the aid of their kin in Ashrafiyyeh-Sehnaya but were ambushed and killed in a deadly trap near the village of Braq, located at the exit of Suwayda province on the crossroads connecting it to Damascus and Deraa. Meanwhile, several villages in the western part of the province were assaulted by tribal groups from Deraa, all loyal to the government. As a result of these five days of violence, 86 civilians and Druze fighters were killed.

Forced to negotiate their surrender, the Druze factions signed an agreement on May 1, which provided for the disarmament of Druze factions outside Suwayda province, the activation of General Security inside the province—on the condition that its members were exclusively recruited from the local population—, and the securing of the Damascus Road. On May 3, al-Sharaa appointed three prominent members of the al-Uqaydat tribe from Shuhayl (Deir ez-Zor) to lead the Intelligence Services, the Supreme Council of Bedouin Tribes and Clans, and the Anti-Corruption Authority, indirectly confirming their involvement in the deadly events of the previous days. Soon after, a checkpoint was established at the crossroads of the Damascus, Deraa, and Suwayda roads and was entrusted to the Bedouin tribes living nearby (Braq, al-Mutalleh, al-Masmiyyeh, Housh al-Hammad)—the very tribes that had attacked the Druze.

…the residents of Suwayda complained about the behavior of the armed men in charge of its management: aggressiveness, intrusive searches, unjustified seizures, and wearing masks and insignia of the Islamic State

In the two months that followed, the residents of Suwayda, who were forced to pass through this checkpoint to reach Damascus, frequently complained about the behavior of the armed men in charge of its management: aggressiveness, intrusive searches, unjustified seizures, and wearing masks and insignia of the Islamic State. In early July, under the pretext of resolving a dispute with these groups, government forces interrupted traffic for several hours, during which the security chiefs of Suwayda and Deraa visited Bedouin hamlets in the region—known for their affiliation with the Islamic State in the last decade—to reconcile rival clans and recruit several dozen of their members into the Ministry of the Interior forces.

On July 11, Druze merchant Fadlallah Dwara was kidnapped near the checkpoint, beaten, robbed of his vehicle, cargo, phone, and money, and then dumped on the side of the road. It should be noted that kidnappings for ransom are a common practice of armed gangs in the region, which, even under the Assad regime, made life and transit along the Damascus Road unbearable. The response came swiftly: the next day, a Druze faction kidnapped Bedouins, prompting retaliation from the Bedouin clans of Suwayda, particularly those from the al-Maqwas district, located at the eastern entrance to the city of Suwayda. Druze civilians were kidnapped in turn.

Al-Maqwas is a neighborhood marked by long-standing conflicts between Bedouin clans, particularly the al-Badah and al-Kaniher, involved in drug trafficking, who expelled the rival al-Anizan clan earlier this year. Linked to the Southern Tribes Gathering, led by notorious drug trafficker Rakan al-Khudair, they initiated the armed hostilities on July 13, before Druze factions — including the criminal al-Qahriyun gang led by Amid Jarira — besieged Bedouin neighborhoods in Suwayda in response to the kidnapping, trapping residents inside, and preventing the wounded from being evacuated to the hospital. The Southern Tribes Gathering fabricated a partially false narrative to justify the government intervention, claiming large-scale ethnic cleansing of Bedouins by the Druze factions led by Sheikh Hikmat al-Hajari, a key opponent of al-Sharaa.

Thus, the coordinated action of the government and the dominant tribes of Suwayda and other regions of Syria led to the combined attack on Suwayda at 8 p.m. on July 13

Thus, the coordinated action of the government and the dominant tribes of Suwayda and other regions of Syria led to the combined attack on Suwayda at 8 p.m. on July 13, despite the mediation of the Druze sheikh Youssef Jarboua, which resulted in the release of hostages from both sides by dawn on July 14.

The attack unfolded in three phases :

- Between July 13 and 15, government forces and their tribal auxiliaries invaded and occupied around thirty villages north and west of the province, up to 5 kilometers from Suwayda. They systematically looted and burned hundreds of homes, forcing tens of thousands of residents to flee south. Druze gang leaders Laith al-Balous and Adnan Abu al-Ezz assisted the invaders in navigating agricultural lands to bypass Druze checkpoints on main roads.

- Between July 15 and 17, after intense Israeli airstrikes on government forces the previous day, Druze leadership negotiated a ceasefire allowing government forces to enter Suwayda city. In the aftermath, chaos ensued as hundreds of soldiers and tribal auxiliaries looted and destroyed homes and businesses, and executed dozens of civilians. Druze leader Suleiman Abdul Baqi helped the invaders navigate within the city.

- After July 17, government forces began withdrawing, leaving the field open for the tribes to continue their massacres until July 21, when they were finally repelled by Druze factions. Since then, government forces have redeployed to the thirty villages previously occupied and evacuated several hundred Bedouin families in preparation for a siege on the remaining population of Suwayda, a siege that has continued since.

During the liberation of Suwayda city and the surrounding villages by Druze factions, more than 1,990 bodies were discovered, close to 1,500 of which were those belonging to the Druze community. Of these, 930 bodies were those of civilians, and the Druze fighters accounted for the other around 550 or so bodies, both having been killed by government forces and Bedouins. Numerous videos, either released by the perpetrators of the crimes or captured by surveillance cameras, leave no doubt about the nature and identity of the criminals. As the province has been under continuous siege since the massacres, with power lines cut, followed by restricted telephone and internet networks, and with almost all entry to and exit from the province made impossible, the dissemination of information now almost exclusively happens through social media and local media outlets. The situation remains far from being solved.

Cédric Domenjoud

Cédric Domenjoud is an independent researcher and activist based in Europe. His research areas focus on exile, political violence, colonialism, and community self-defense, particularly in Western Europe, the former USSR, and the Levant. He is investigating the survival and self-defense of Syrian communities and developing a documentary film about Suwayda, as part of the Interstices Fajawat project (interstices-fajawat.org).