Baghdad, Erbil: Pollution Is Causing Health Crises

In Baghdad and Erbil, greenhouse emissions and illegal refineries are poisoning residents. Authorities insist they can manage the crisis with short-term campaigns and flagship projects, but in the meantime public trust is eroding, public spaces are drying out, and public health is taking the hit.

Despite international agreements and statements of commitment to the UN Sustainable Development Goals, both Baghdad and Erbil are trapped in reactive short-term environmental governance that cannot counter structural pollution drivers, and the past few weeks exposed the fragility of the proposed solutions and the desperate necessity for genuine remedies.

Baghdad: Smog and Public Health Crises

Early one morning in December 2024, I was in Baghdad for a meeting. With time to kill before the meeting, I decided to walk around the city, enjoy the view of the Tigris, and perhaps visit the shrine of Imam Abu Hanifa in al-A’dhamiya area. I went out and very quickly noticed that the sky had a strange colour: not quite blue, but not grey either. And despite technically being winter, the sun had warmed the city up to a balmy 25℃.

Nearly 30 minutes later, it hurt to breathe, my throat started to itch, and there was an unpleasant sour taste in my mouth. At the time, I assumed it was a seasonal anomaly. It wasn’t.

A year later, in late November 2025, Baghdad was ranked among the most polluted cities in the world, with an Air Quality Index (AQI) sometimes reaching 252 – whereas clean air has an AQI of 0-50 – pushing the Iraqi capital into the purple category, a level considered hazardous for everyone.

Weather experts linked the sudden surge with stagnant air, industrial emissions, and open waste burning, while monitoring platforms recorded a PM2.5 value (fine particulate matter suspended in the air, tiny in diameter and hazardous to breathe) several times above the World Health Organization (WHO) standards, ranking Iraq, the cradle of civilisation, as one of the world’s most polluted countries.

Authorities initially dismissed the grey veil over the capital as “natural and temporary” atmospheric conditions and a seasonal occurance that will disappear when the weather changes. A day later, the Environmental Ministry acknowledged that the smog consisted of trapped exhaust from refineries, power plants, brick and asphalt factories, electricity generators, and the millions of vehicles darting from one end of the city to the other, creating a public-health emergency.

As officials were publishing statements about the crisis, hospitals saw an influx of patients, with many residents reporting breathing problems.

Baghdad’s sudden spike is not new. The city has failed to mitigate garbage burning on its peripheries and even inside densely populated centres.

Camp Rashid in the capital’s southeast has become a symbol of this failure, where garbage bonfires and construction debris have burned for years, sending toxic fumes across the metropolitan area. Following the November smog, officials moved to close its gates, as they now admit that this is only one piece of a wider problem.

Another factor exacerbating the problem are industrial facilities, who frequently exceed emissions limits with few consequences.

Water sources are likewise facing existential threats: planned sewage treatment plants and drainage networks have been delayed for decades, leaving untreated water to spill into the Tigris, the lifeblood of millions in the country.

The result is a capital encircled by dumps, choked by exhaust, and flanked by rivers which faces rising pollution and falling water levels.

In recent years, Baghdad’s PM2.5 has averaged 45.8 µg/m³, about 9.2 times above the WHO guidelines’ of 2.5 µg/m³, placing the capital among the top 10 most polluted cities globally.

This is not an accident of weather, but a consequence of deliberate choices. After the 2003 US invasion, war, insurgency, and constructions stripped the city of much of its orchards and tree belts that once circled Baghdad, as security and profit took precedence of the capital’s “lungs”. And official plans for a green belt were either not completed or steadily eaten away by unregulated construction, housing, or commercial projects.

At the national level, former president Barham Salih’s Mesopotamian Revitalization Project promised a strategic shift on water, climate, and energy. But most of its proposals have remained on paper, with little visible impact on how Iraqi cities manage air, rivers, or land.

The recent spike shows Iraq’s problem: a country where authorities speak the language of climate action and environmentalism, while the population breathes the opposite.

Erbil: Planned Improvement

Erbil’s weather crisis has been slow and constant, albeit on a significantly smaller scale than Baghdad,

In 2023, the Kurdistan Region’s capital’s average PM2.5 stood at 30.4 µg/m³, placing it as the 10th most polluted city in West Asia.

In Erbil, residents live with a perpetual haze of exhaust emitted by a reported 85 illegal refineries, and car and power generator fumes that thicken in the scorching summer heat. In winters, a veil of smoke drapes city’s skyline, slowly choking its two million residents.

December 2024, youth from Erbil launched a campaign on Instagram stories, calling on authorities to tackle the pollution problem. “We can’t take this anymore. The air is killing us. KRG, act now!” read the story template shared by thousands.

The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) points to two flagship projects as evidence of Erbil being on a different trajectory than Baghdad: Runaki, the project to provide 24-hour electricity, and the plans to establish a protective greenbelt around the city, essentially creating a new set of lungs for the capital.

Announced in 2024, Runaki promises to provide uninterrupted power to households and businesses all over the Kurdistan Region by the end of 2026. In doing so, the project ends the era of privately-owned petrol power generators, which for nearly two decades provided power when the national power grid did not. By shutting down the generators, Erbil’s air should gradually become cleaner.

In June, the KRG stated that it had shut down shut down around a quarter of the generators in the Kurdistan Region, reducing 240,000 tons of CO2 emissions, equalling the removal of 250,000 cars on the streets.

However, Erbil’s problems extend beyond just generators; unlicensed and unregulated refineries are, allegedly, still running on the outskirts of the capital, despite government crackdowns; while the Erbil governorate has given legally working refineries a grace period to adapt before enforcing environmental regulations. In July, Erbil Governor Omed Khoshnaw told Ava News that they have shut down about 85 illegal refineries – about half of the reported 140 in operation.

Green Spaces

The lack of green areas, parks, trees, and green canopies in cities are a major factor for cities overheating and trapping pollution, instead of dispersing it; these problems are also present in Erbil.

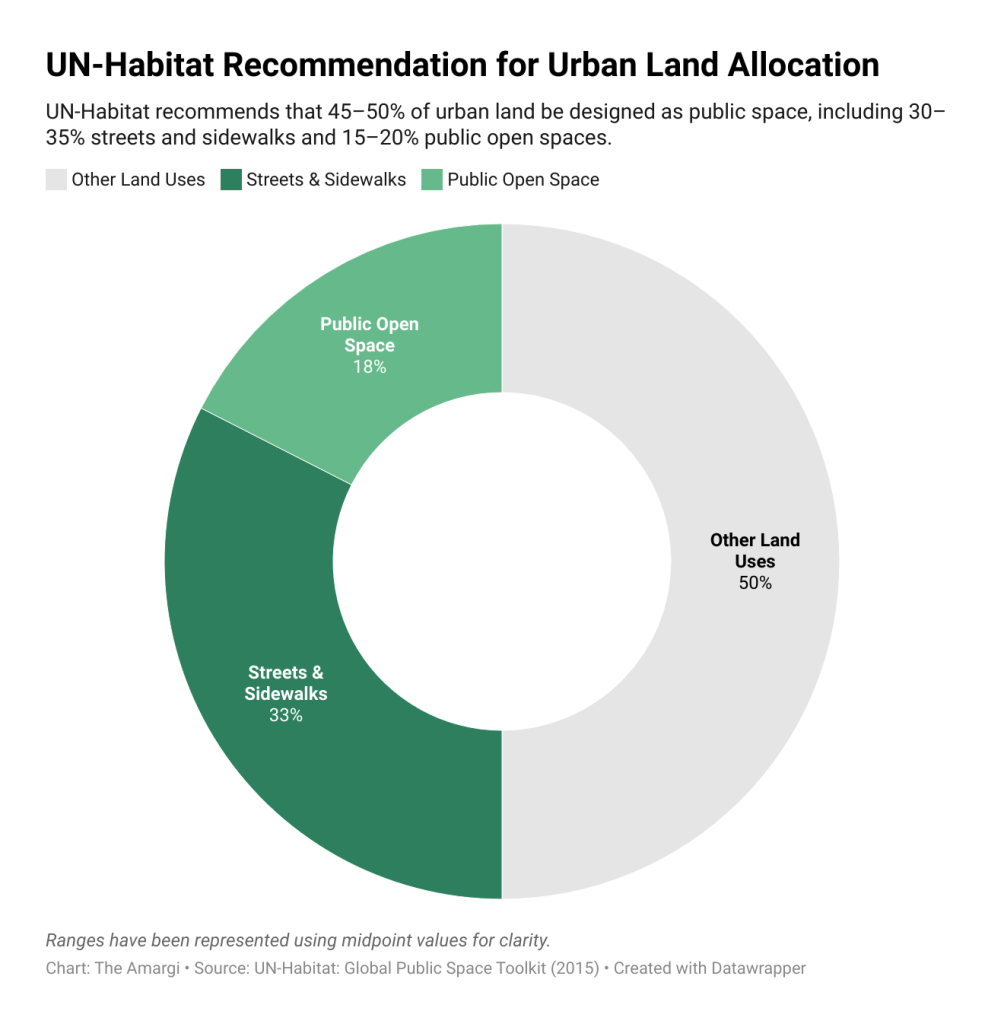

UN Habitat recommends “an average of 45 – 50%of urban land be allocated to streets and open public spaces, which includes 30 – 35% for streets and sidewalks and 15 – 20% for open public space,” while defining the public space as “all places of public use, accessible by all and comprises streets and public open spaces.”

Officials in Erbil claim that the city’s green spaces pass the standards with flying colours, at 19.8%, a surge from 9.1% a decade ago. However, a walk around Erbil and its barren pavements begs to differ. Much of the “green” is concentrated in traffic islands, fenced villa compounds, and golf courts.

The WHO recommends short distance and easy access to public green spaces – 0.05—0.1 km2 of green space no farther than 300 meters linearly from residential areas – but in Erbil, neighbourhoods are dominated by concrete and car parks, with few trees scattered along stretches of bare pavement and asphalt, leaving residents exposed to heat, polluted air despite the optimistic headline figures.

The Greenbelt initiative is an encouraging step in the right direction for the city over the long haul. But trees require years to mature, and the scale of planting to meaningfully affect air quality has not yet matched the pace of urban sprawl, construction, and the increase in vehicle numbers.

A 2025 study on urban forest projects published in the Science of The Total Environment journal shows that an urban forest can become carbon net positive after approximately 13 years. In other words, Erbil’s greenbelt needs around 13 years to impact the atmospheric carbon.

While the timeframe to meaningfully reduce the CO2 emissions from vehicles, generators and industrial activities is not as immediate as many would have hoped, the greenbelt can in the meantime help filter dust and other pollutants and cool urban areas.

Reinforcing Initiatives

Baghdad announced new inspection teams, fines, closures, and constantly emphasizes the need to abide by the UN Sustainable Development Goals. And Erbil has shut down dozens of unlicensed refineries around the city.

But short, reactive campaigns are not the solution.

Studies tie Iraq’s pollution not only to singular bad actors, but to structural issues: fossil fuel-dependent power grids, gas flaring, weak regulations and car-centric metropolitan centres. For the two cities, short-term campaigns may slightly lower AQI peaks, but they will not prevent the next suffocating week of pollution, haze, and sandstorms when emissions remain unchanged.

Without binding standards for fuel quality, aggressive public transport investment and revamp, a serious crackdown on illegal and substandard refineries operating in open-air, as well as systematic enforcement, and waste-management reform, both cities will stay trapped in cycles of emergency alerts and worsening health crises.

Azhi Rasul

Azhi Yassin Rasul is a multidisciplinary researcher and writer based in Madrid. His work sits at the intersection of urban analytics and storytelling. With experience spanning journalism, urbanism, and engineering, he focuses on understanding how cities function and how policy, design, and lived experience converge. He has reported from the field and covered topics spanning Kurdish politics across Iraq, Turkey, and Syria, as well as environmental issues.