Freedom in the Air: Khalil’s Neighbours

Looking at the border, Shero’s grandfather tells him a story. Once upon a time, a French and English military truck carrying soldiers arrived here. People were living together as one community. They divided the people. One part stayed on the left, and the other on the right. Borders and wires were placed between them.

“Why didn’t the people stop them?” Shero asks.

“They were faced with bullets and death,” his grandfather replies.

Those above the line were forced to be Turkish, and those below, to be Arabs, severing family ties. Colonial and imperialist structures constructed the modern border. By violently imposing imagined and artificial borders and nation-state governance, the diverse fabric of society was fractured

Shero is the protagonist of “Neighbours” (2021), directed by the Kurdish-Swiss director Mano Khalil. Displaced by the Syrian war in 2011, Shero, in his forties, lives in a refugee camp in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Through flashbacks, Shero recounts his early childhood experiences with education and border life in the 1980s, when he was six years old.

Shero and his uncle, Aram, hide in a trench at the Syrian-Turkish border. As a challenge to the border authorities, they release three balloons with the Kurdish resistance colors —green, red, and yellow — into the sky. Only the open sky is free to contain the Kurdish colors. The Turkish guards fire the balloons with hysterical abandon. They shot the yellow and green balloons, yet the red one elevated higher than their bullets. The scene symbolizes the resilience of the Kurdish identity against oppression. As the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish once wrote, “The Kurd has nothing but the wind.”

On Eid, the family meets the rest of the members, who live on the other side of the border, to exchange greetings, kisses, gifts, and share the latest news from their lives. The thorny wires separate them from each other, and interaction is distant. Border guards from each nation-state shout at their “non-citizens” to speak the official language of the country. The longings and intimate moments of the family members are interspersed with insults and injuries from the fence. Upon the slightest complaint from the members, weapons are ready to respond. The Eid, a joyful ceremony, becomes an “Eid of humiliation”. Borders not only violently enforce national identities but also erode cultural and familial bonds.

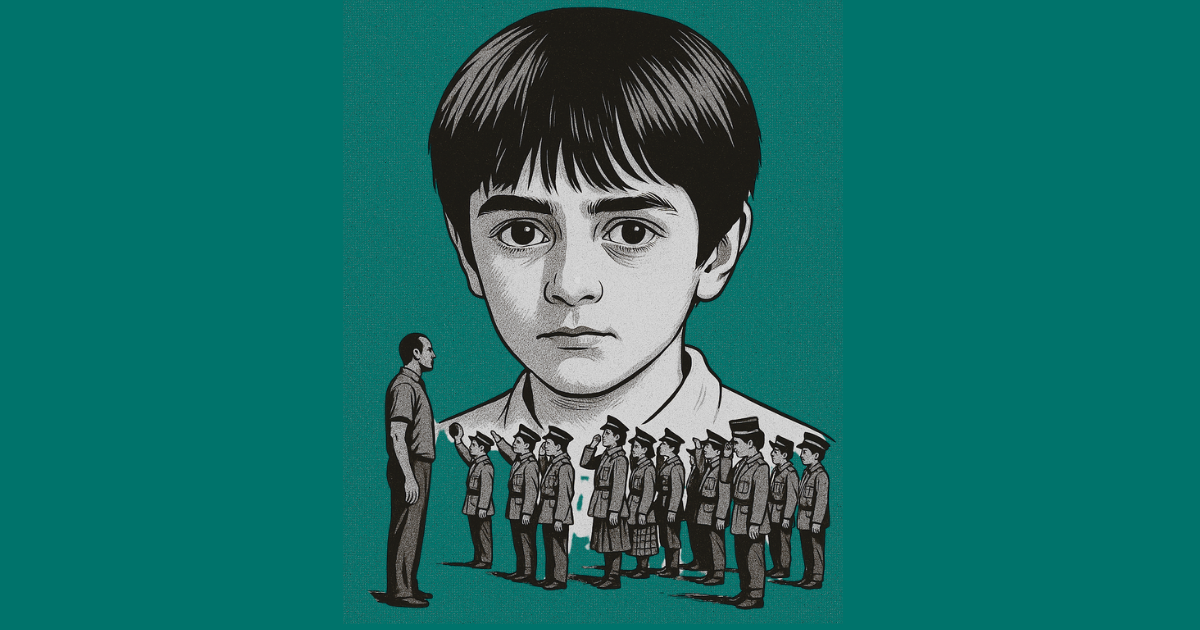

Shero leaves the house after a kiss from his mother to attend his first day of school. He wears a school uniform. In the schoolyard, the students line up in random order. The Ba’athist teacher (Wahid) appears with a stick in his hand. He strictly lines the students up, arranges their bodies, and prepares them for the flag salute in the morning. After reciting Ba’ath Party slogans and praise to the leader Hafez al-Assad, the students enter the classroom. The teacher asks them to call him “comrade,” since he and the students are now part of the Ba’ath Party Vanguard organization. He begins his preaching about his role, which is to liberate the Kurdish remote village from ignorance and backwardness. To achieve this, students must learn Arabic, immerse themselves in it, and practice thinking and speaking in Arabic both at school and at home with their partners. “There is only one language,” he declares, “Arabic”. Those who fail to learn it are punished physically. The school is a machine that reproduces the dominant ideology, Arab nationalism, and functions as a factory for discipline, assimilation, and internalized colonization of differences through violence.

Even though the soil in Qamishli is not suitable for growing palms, the schoolteacher (Wahid), with the help of Djasim, planted a palm in the village, as it is the symbol of the Arab nation. Djasim is a transplant from the Arab belt, implanted among the Kurds to choke their tongues.

In a remote village with no electricity, “Can one pray in Kurdish?” Shero asks. “I will ask God to bring us a TV.” Shero wants to watch cartoons on TV, just like children in the city.

When the state brought electricity, the schoolteacher, Wahid, was elated, boasting that light would bring enlightenment and progress. Shero’s father bought a TV and placed it on a small wooden table. The whole family gathered in front of it. As the screen lit up the room, all Shero’s dreams were shattered. The face of Hafez al-Assad, speeches of war, military training, and Al-Ba’ath slogans appeared instead of cartoons. The same ideological propaganda he was trying to escape in school had now entered his room through the only channel broadcast in Syria. Light becomes the darkness of power. Power does not remain within state institutions. It stretches outward, invading one’s private sphere through the media.

At the border, two Turkish soldiers are stationed in a watchtower to observe and control movement. Below, Shero’s mother walks to the river to wash the clothes near the border. One of them leers at her through his sniper scope. The other jokingly taps the trigger of the sniper rifle with his pen, a pen to write a letter to his mother about his daily routine in serving his nation’s duty. Shero’s mother falls dead. This scene becomes the alphabet of the patriarchal roots of the border, where the syntax of power, patriarchy, territory, and its transgression are woven into acts of killing.

Next door to Shero, Nahum lives with his wife and daughter (Hannah). Their home is a quiet corner of safety and tranquility where Shero can breathe, if only for a short time. Under the tyranny of repression, the calm is fragile. Being Jewish, Nahum and his family are considered a “suspect community”. The geopolitical landscape outside the village heavily burdened their lives. When they appear in the film, the camera’s lighting is dim. It reflects their uncertain destiny and anxiety. Travel papers are forbidden. Inside their house, three languages are intermingled: Hebrew, Arabic, and Kurdish. Amid rising anti-semitic policies against them, Nahum is forced to send his wife and daughter to Switzerland with forged papers, thanks to Shero’s father. Nahum ultimately dies alongside his Kurdish neighbours. Hannah’s love story ends with Aram when he joins the Kurdish movement due to oppression and to escape compulsory military service by the Syrian state, while Hannah is forced to leave Syria for being Jewish. The nation-state tolerates no diversity beyond its rigid lines.

Alienated by the educational system, Shero dozes off and daydreams of his late mother in the classroom. Shero walks towards her in the field, along the border. She smiles at Shero and releases yellow, red, and green balloons into the sky, and then hundreds of other similar colorful balloons join to fill the sky, capturing the power of imagination to transcend political and social structures that confine reality.

Many decades later, Hannah, Nahum’s daughter, visits Shero in the refugee camp from Switzerland. Hannah was a friend of Shero’s when he was little. Hannah hugs Shero with a tender, deep, humane hug. “Neighbours” closes with this. In the face of all loss, exile, and suffering perpetrated by the cold logic of the nation-state, the heart’s warmth and solidarity persist, offering a hopeful ending.

Cihad Hammy

Cihad Hammy studies English and American Studies (Master’s) at the University of Hamburg. He is a researcher and the co-editor of Rojava in Focus: Critical Dialogues.