Jalal Talabani’s 1980 Letter to A Naqashbandi Sheikh: Civil War in East Kurdistan and its Relevance Today

In recent weeks, religious scholar Mullah Hama Yousef Kochar has found himself at the center of a political storm that reaches back nearly half a century. Kocher’s controversial memoirs, and a long-forgotten letter from a Kurdish political leader, have rekindled debate over Kurdish infighting, foreign patrons, and who controls the story of the past.

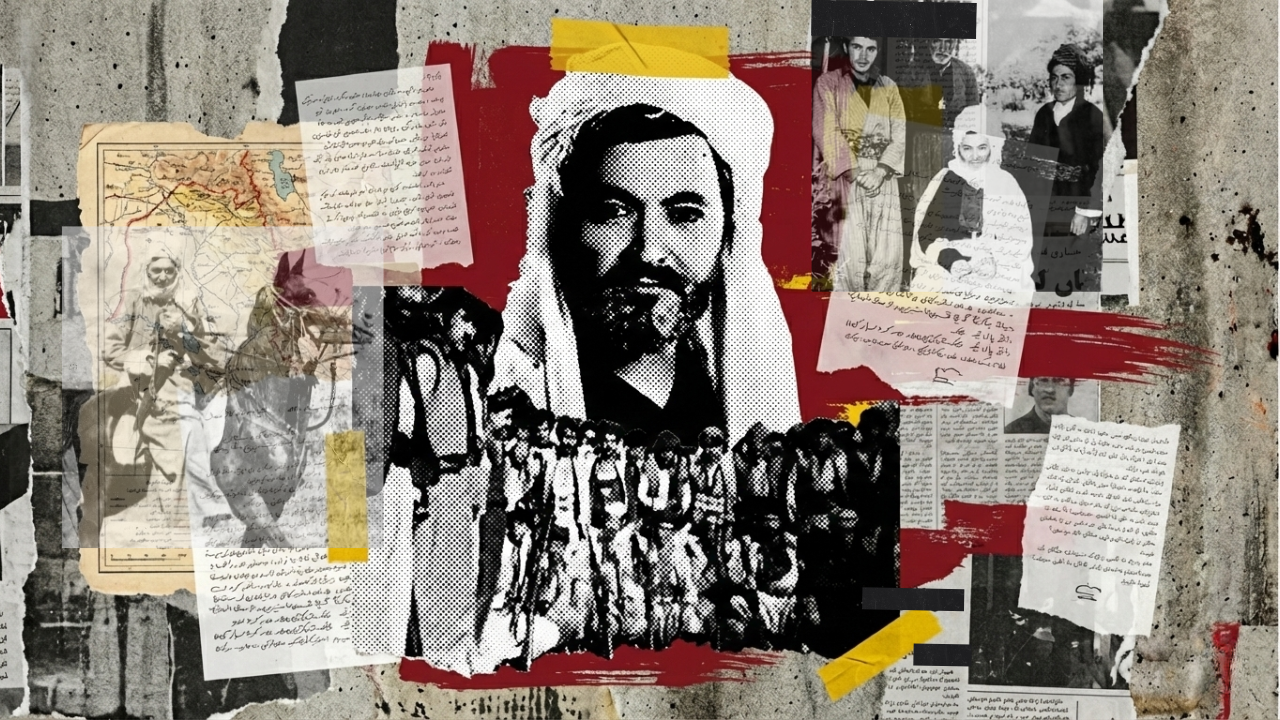

Kochar devoted a few pages of his newly published memoir to the “Liberation Army”, a militia formed in the mountains of East Kurdistan (Kurdistan region in Iran) in the turmoil following Iran’s 1979 revolution. It had roots in the religious Naqshbandi Sufi order and was led by the powerful Sheikh Osman Naqshbandi. They fought the new Islamic Regime in Tehran, with weapons and money allegedly flowing from Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

Kochar was blunt in his judgment: he argued that the Liberation Army should never have been created, and that accepting aid from Baghdad, which had been responsible for mass atrocities against Kurds, was a grave mistake. He criticized Sheikh Osman for “following the tide,” and putting his hope in the Iraqi Ba’athist regime to help topple Iran’s new rulers. He also faulted the Liberation Army for taking part in Kurdish infighting and contributing to the deaths of many Kurdish men.

The reaction was swift: followers of the Naqshbandi order in Kurdistan accused Kochar of defaming a revered religious leader and falsifying history. And religious scholars and self-identified disciples of the order organized a social media campaign to pressure him into making retractions.

And, although Kochar publicly apologized in a video for any factual errors, at least one scholar of the Sufi order has now demanded that Kochar pull his book from bookstores and issue a revised edition with all mention of the Naqshbandis removed.

At first glance, this appears as a relatively normal, albeit potentially litigious, disagreement rooted in a writer’s right to re-examine the past and the sensitivities of a religious community. Yet, within the context of Kurdistan’s history, the fight over a few contested pages has opened an old wound that cuts to the core of modern Kurdish politics: the bitter civil wars of the late twentieth century and the rivalries between movements that still shape events across the region today.

A Small Sufi Army in a Crowded War

When the Shah of Iran fell in February 1979, East Kurdistan was a hodgepodge of rival armies. Kurdish nationalists of different ideological shades, left-wing organizations, remnants of the Shah’s royal army, local tribal forces, and the Revolutionary Guards of the new Islamic Republic all pushed for territory and influence across the mountains of western Iran. Control of towns and valleys shifted frequently, and alliances were as fluid as the front lines.

Amid the turmoil, Sheikh Osman Naqshbandi, an old but influential Sufi leader whose networks straddled the Iraq—Iran border, entered the complex maze of post-revolution politics. He formed the Supayî Rizgarî, the Liberation Army, and filled its ranks with devoted followers from the Hewraman region. Kurdish studies scholar Martin van Bruinessen has described the militia as “a dervish army” of Naqshbandi disciples who saw themselves defending both their religious order and their community.

But the Army found itself fighting more than one enemy in the rugged terrain of Hewraman and its surroundings.

According to van Bruinessen, Sheikh Osman created the Liberation Army largely for defensive and political reasons, as before the revolution, the sheikh had been close to the Shah, and the Kurdish Naqshbandi tradition to which he belonged was steadfastly Sunni – and deeply suspicious of Shiite dominance. These reasons made him fear Iran’s new rulers, who were anti-Shah, anti-Kurdish, and anti-Sunni. He was convinced that in a fragmented Kurdish landscape, where no single force held total sway, only an armed following could preserve his influence.

As Kochar writes, Baghdad, then under Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath Party, saw an opportunity in this. Having granted Sheikh Osman refuge, they encouraged the move and supplied much of the Liberation Army’s weaponry.

But the Army found itself fighting more than one enemy in the rugged terrain of Hewraman and its surroundings.

Clashes with the leftist Kurdish group Komala and other Kurdish formations became more frequent than battles with the Regime forces. Komala regarded the sheikh as a “landlord and class enemy”, organizing landless peasants against traditional elites. Many in the Liberation Army, in turn, denounced their Kurdish leftist compatriots as “godless” and considered Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (Pasdaran) a lesser evil.

That pattern, Kochar’s memoirs have reminded readers, had a deadly cost: the Liberation Army was drawn deep into intra-Kurdish warfare.

…the Liberation Army was decisively defeated because many of its men … were reluctant to fight fellow Kurds

Hatam Minbari, a veteran of the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran (KDPI), in his memoirs titled Agonies and Experience, has depicted the Liberation Army as a rapidly growing actor that was backed by Ba’athist Iraq, not, as many had originally suspected, by the Shah’s supporters.

Minbari recounts how Komala moved against the Naqshbandi fighters in part out of fear that the Liberation Army and the KDPI would form an alliance against Komala.

KDPI later joined Komala, and the Liberation Army was decisively defeated because many of its men lacked combat experience and were reluctant to fight fellow Kurds. Some later joined KDPI.

Kochar’s critics accuse him of oversimplifying this tangled history and tarnishing the reputation of a religious order that has long been central to Kurdish public life. Others argue that recounting such events, based on firsthand memories and political assessments, is exactly what memoirists and historians are supposed to do – that both Iraqi law and international human rights norms protect that right.

A Letter of Warning, Written In 1980

One document, a handwritten letter, from that era has come to light, potentially adding to the history of the Liberation Army. How the letter was brought to light is also worth emphasizing: initially published by the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), whom the Liberation Army fought, in a book titled Kurdistan, Imperialism, and Affiliated Groups.

The letter helps to connect the Liberation Army to the broader rivalry that has dominated Kurdish politics for the last fifty years and the struggle between the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK).

On March 12, 1980, Jalal Talabani, co-founder and then Secretary General of the PUK, wrote a letter to Sheikh Osman Naqshbandi. Talabani reminded the sheikh that they had a long-running cordial relationship that they both valued, even when other Kurdish and Iranian parties criticized that friendship.

Talabani expressed concern about the sheikh receiving arms and cash from “our enemy, the Iraqi government,” and, simultaneously, had entered into cooperation with another of the PUK’s enemies at the time: the KDP. In the letter, Talabani used sharp words, describing both Baghdad and the KDP as “murderers of the Kurdish people,” a stark phrase that reflected the lingering bitterness over the collapse of the Kurdish revolt in Iraq in 1975, Kurdish disunity, and the subsequent years of repression and massacre.

Talabani urged Naqshbandi not to accept further aid from Saddam Hussein’s government and stressed that this was not a request directed only at the Sufi order. He added that he conveyed the same message to all Kurdish parties.

In Talabani’s view, the Kurdish revolution should “depend on itself, the Kurdish people, and God,” not on regimes that had repeatedly killed and massacred Kurds. Talabani also subtly acknowledged that most Kurdish parties in Iran were, in one way or another, also receiving support from the Iraqi regime.

The letter delves into several layers of the conflict. It shows how religious authority still commanded respect from modern party leaders. It captures the PUK’s worry that the Liberation Army, enjoying Iraqi support and linked to the KDP, might tilt the balance of power in eastern Kurdistan. And it documents the mistrust between Kurdish factions, who often saw one another, as much as Arab or Persian rulers, as existential threats.

KDP and PUK’s Long Rivalry

By 1980, intra-party tensions had dug deep roots. The KDP, founded in 1946 and led for decades by Mulla Mustafa Barzani, had waged intermittent rebellion against successive Iraqi governments, culminating in the First and Second Iraqi–Kurdish Wars of the 1960s and 1970s. The second of these conflicts ended in defeat after the 1975 Algiers Accord between Iran and Iraq, which cut off Iranian support for the Kurds and forced Barzani’s movement into exile.

During the Iran–Iraq war that began in 1980, the rivalries deepened. Both parties played a dangerous game of balancing reliance on neighboring states that were themselves at war.

In the wake of that collapse, Talabani and several associates broke from the KDP and founded the PUK in 1975. The new party combined Talabani’s own supporters with leftist cadres and other dissidents, many of them based around Sulaymaniyah and the eastern parts of Iraqi Kurdistan. While the KDP retreated into Iran and sought to rebuild, the PUK launched its own insurgency against Baghdad in the late 1970s, sometimes clashing with former comrades in the KDP as both sides competed for dominance.

During the Iran–Iraq war that began in 1980, the rivalries deepened. Both parties played a dangerous game of balancing reliance on neighboring states that were themselves at war.

Talabani’s PUK at times moved closer to Tehran and Damascus, while the KDP nurtured its own ties with Iran and later with Western powers. And each accused the other of selling out Kurdish interests for tactical advantage.

The Liberation Army, with its Ba’athist backing and perceived closeness to the KDP, entered this landscape as a smaller but symbolically important actor. PUK units harassed its forces and reportedly cut key supply lines, reasoning that a Naqshbandi army sponsored by Saddam Hussein could not be allowed to consolidate itself in an area where the PUK was fighting the same regime.

By the early 1980s, the Liberation Army had faded from the battlefield. Martin van Bruinessen has argued that this last Sufi Army did not succeed because it was politically isolated, militarily outmatched, and socially out of step with the times. Backed by Ba’athist Iraq and drawn into violent clashes with other Kurdish groups, it alienated many Kurds – just as stronger parties like KDPI, Komala, and the PUK were consolidating real grassroots support and cutting its supply lines. Many of its largely Naqshbandi fighters were inexperienced and reluctant to fight other Kurds, and Iraqi backing was waning.

Sheikh Osman eventually left the region, spending time in Europe and Turkey before settling in Istanbul, where he died in 1997 at the age of 101. The networks of the Naqshbandi order persisted, but the Liberation Army itself exists only in history now.

Old Battle Lines in a New Era

The legacy of those years is not confined to memoirs and archival letters. The KDP and PUK remain the two dominant forces in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Their rivalry has periodically flared into open war, most notably in the early 1990s, when thousands died in the Kurdish Civil War, which in Kurdish is referred to as the “War of Fratricide”.

It is against this backdrop that the controversy over Kochar’s memoirs takes on a broader meaning. The Liberation Army is no longer a military force, but its history touches on the reputations of powerful religious families, on the record of the Baathist state in manipulating Kurdish divisions, and on the uneasy relations among Kurdish parties in both Iran and Iraq.

It also resonates with more recent events. Last year, Madih, a surviving son of Sheikh Osman and a former leader of the Liberation Army, returned to Kurdistan after four decades in Britain. Now in his mid-eighties, he received a warm welcome at Erbil Airport from KDP officials, which some view as a symbolic repayment for the sheikh’s past support during some of the most difficult moments in the KDP’s history.

For Talabani, writing in 1980, that kind of intimacy between a Sufi leader and the KDP, buttressed by Iraqi arms, posed a mortal danger to what he called the “Kurdish revolution.” For Kochar, writing decades later, it raises uncomfortable questions about who fought whom, and on whose payroll.

Renwar Najm

Renwar Najm is an Iraqi Kurdish journalist with a career that began in the early 2010s at the esteemed Awene newspaper. He holds a master’s degree in Peace and Conflict Studies from the University of Kent and Philipps University of Marburg.