Gold and Guns Fuel War in Sudan

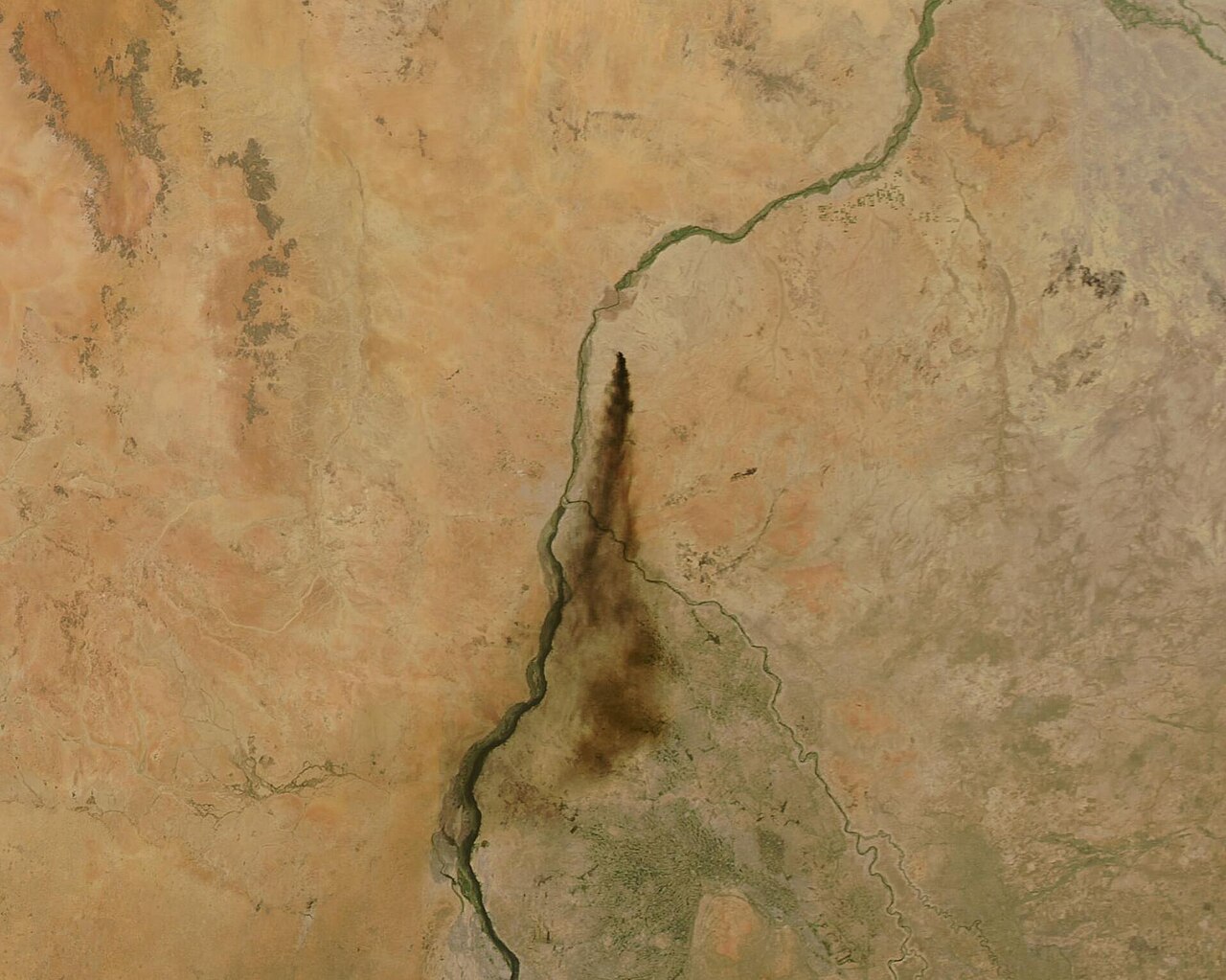

A fire at the Al-Jaili refinery, which is located about 60 kilometers (40 miles) north of Khartoum, caused when it was overtaken by RSF in January 2025. Captured by the the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite. Picture Credits: NASA/Wikimedia Commons

A fire at the Al-Jaili refinery, which is located about 60 kilometers (40 miles) north of Khartoum, caused when it was overtaken by RSF in January 2025. Captured by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite | Picture Credits: NASA/Wikimedia Commons

Years after it started, Sudan’s gold continues funding its devastating civil war. And as foreign military support has ramped up, human rights organizations have reported incidents of genocide and ethnic cleansing.

In the small town of Alkufra, in Haftar-controlled southeastern Libya, soldiers unload crates of weapons and ammunition. The cargo crates hold Chinese-made drones, heavy machine guns, vehicles, artillery, mortars, and ammunition, and, based on a United Nations report, they come from the United Arab Emirates (UAE). According to the UN, the crates are then transferred onto trucks and driven into Sudan while being escorted by armed Land Cruisers.

At the border to Darfur, the shipment is handed over to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia, which has been accused of ethnic cleansing in Sudan’s civil war. And in a dark twist of fate, oftentimes these weapons have been smuggled through under the guise of humanitarian aid deliveries to civilians, The New York Times reported in September last year.

“This isn’t simply a ‘gold-for-guns’ trade,” said Jalel Harouchi, a researcher at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI). “The UAE spends far more than any gold it receives; its support isn’t a transaction. It’s a strategy.”

Payment, though, is often made in gold. Gold, which has been mined in a country that many fear is violently destroying itself.

Former Allies

The war began after two military generals ousted Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir in 2019, he himself having been in the position thanks to a 1989 coup.

Often called “the generals’ war,” the conflict continues to be between Sudan’s army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo, leader of the RSF militia.

The two men jointly overthrew al-Bashir and, in the aftermath, agreed to share power with a civilian transitional government. Two years later, they staged a military coup, removing the civilian leadership. But ruling the country together proved impossible, and on April 15, 2023, they went to war against one another.

Ethnic Cleansing Accusations

Both the RSF and the Sudanese army have exploited ethnic divisions to rally support, and both have attacked civilians from rival communities. Additionally, the two sides have also collaborated with smaller rebel groups across the country.

In the last week of October, the RSF captured the city of El-Fasher in Darfur, after 18 months of siege, bombings, and starvation. Reports describe executions, sexual assaults, looting, and abductions in and around the city.

Talking about the RSF’s conduct, senior advisor at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, Ruben De Koning, referred to RSF’s roots in the Janjaweed militia, “There are many similarities to what happened with the Janjaweed in the 2000s”.

The infamous Janjaweed militia was accused of genocide in Darfur two decades ago. Hundreds of thousands were killed and millions displaced when Darfuri rebels took up arms against the government.

“The same ethnic groups are being targeted again.” He said, “The big difference is that the RSF is now fighting against the government, not for it.”

Today, the Masalit, Zaghawa, and Fur peoples have become main targets of RSF attacks in Darfur. These non-Arab ethnic groups have cooperated with the army in defending El-Fasher, a decision which the RSF has used as justification for its assaults.

Tens of thousands are believed to have fled massacres and assaults in the city. Refugees from El-Fasher have said they were attacked because of their ethnicity and skin colour. “They beat us with sticks and called us slaves,” said Hussein, one of the survivors, to the AFP news agency.

Foreign Support Keeps the War Alive

Without outside support, neither side could sustain this war. The conflict has become even more complex as neighbouring states and global powers have stepped in.

“RSF has had several sources of weapons and fuel during the war, but the main supplier remains the UAE,” said De Koning.

The RSF has been receiving backing from the United Arab Emirates, Chad, Libya, and South Sudan.

Harouchi added that the UAE’s support surged after the May 2025 bombing of the Nyala Air Base in Darfur, which he called a pivotal turning point. “After Nyala, the UAE doubled down,” he said. “Deliveries and mobilization became far more assertive.”

Additionally, several hundred former Colombian militia fighters have reportedly also been within the RSF ranks. According to Middle East Eye, these mercenaries were flown by Emirati aircraft to neighbouring countries and then smuggled into Sudan.

The UAE has denied all such accusations.

Countering the reported UAE support, the Sudanese army has received weapons and drones from Turkey, Qatar, Iran, and Egypt.

However, identifying the sides involved in this conflict is not so straightforward. Amnesty International has written that China has been a central player and has allegedly sold arms to both factions. And according to The Economist, Russian mercenaries have fought for both camps in the conflict. In return for Russia’s military support, Sudan’s government has reportedly allowed Moscow to build a naval base in the city of Port Sudan.

Sudan’s Gold Became the Fuel of War

Sudan was among the poorest countries in the world, even before the outbreak of the civil war. Despite the country’s wealth of natural resources, especially gold, the country’s 46 million population has long struggled with poverty, with a GDP per capita of just over $700 in 2019. That gold was a principal cause of conflict, though, as control of the gold mines was one of the main reasons that the civil war erupted in April 2023.

“Gold is a central resource for both sides,” De Koning explained. “Each faction is now trying to block the other’s access to it.”

Harouchi noted that the RSF’s pre-war control over much of the gold sector gave Hemedti an advantage that has only grown during the conflict. “A lot of Sudan’s gold is in Darfur,” he said. “The Burhan camp now controls only a small fraction of daily production.”

One of the mines – the Sungo mine in Darfur, owned by General Hemedti’s family – has provided crucial income for the RSF. The war initially halted nearly all gold production, but it has since rebounded, reaching its highest levels in six years.

Adding to the RSF’s resources, during the years of war, the price of gold has soared. In 2024, Sudan produced 80 tons of gold – an output that was valued at around $6 billion.

“The gold industry employs up to a million people,” said Ahmed Soliman, a Sudan expert at Chatham House. “But in the end, those resources are used to destroy the country. The money goes to buy weapons, allowing both sides to tear Sudan apart.”

The Amargi

Amargi Columnist