Kurds, Syriacs and Armenians Uprooted in Turkish-Controlled Northern Syria, Report Finds

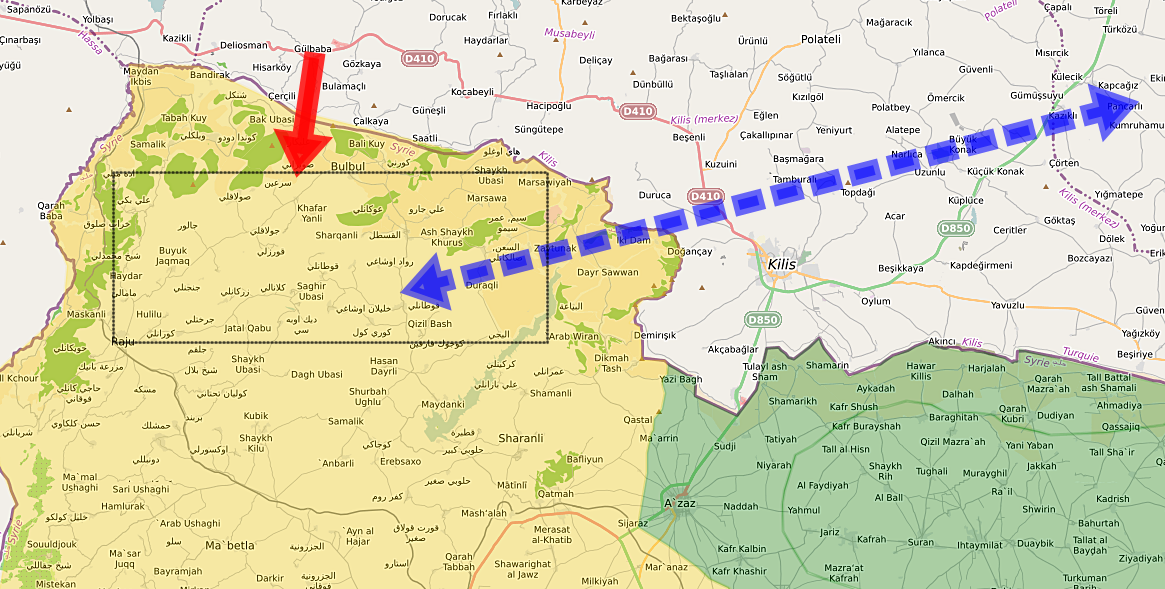

Turkish Army and Air force of Turkey elements hit YPG / PYD targets in Afrin, Syria (Open Street Map).

Red: Entry route of Turkish armored troops, soldiers and artillery (Gülbaba Village)

Blue: Operation route of Turkish F-16 aircraft (Diyarbakır Air Base)

Turkish Army and Air Force elements hit YPG / PYD targets in Afrin, Syria (Open Street Map).

Red: Entry route of Turkish armored troops, soldiers, and artillery (Gülbaba Village)| Blue: Operation route of Turkish F-16 aircraft (Diyarbakır Air Base) | Photo Credits: Wikimedia Commons

Six years after a Turkish military offensive seized control of several Kurdish-majority cities, including Afrin in March 2018, and Ras al-Ain, and Tell Abyad in October 2019, the region remains affected by displacement, demographic change, and widespread human rights abuses. Rights groups claim that more than 150,000 people have been uprooted, 52 villages emptied, and thousands detained or tortured under the rule of Turkish-backed factions, making the prospect of a safe and voluntary return increasingly remote.

Based in Qamishli in northeastern Syria, the Synergy Association for Victims (hereafter, Synergy) was founded in March 2021 by a group of Syrian victims to empower others like them to represent themselves, demand their rights, and actively participate in efforts towards justice and accountability. Synergy is a member of the Human Rights Reference Group of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the International Network of Victims and Survivors of Grave Human Rights Violations.

Orhan Kamal, its coordinator, told the Amargi that the association works closely with the interim government in Syria, the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, and various UN agencies to amplify victims’ demands for a safe and dignified return to their homes after the fall of the Assad regime.

“A violation remains a violation regardless of the perpetrator, and those responsible must be brought to justice.”

Kamal asserted that Synergy encourages victims to organize themselves through initiatives such as the Platform for Families of Missing Persons in Northeast Syria, which includes 750 families, and the Statelessness Network in Hasakah. These initiatives, he added, are also led by victims of the war and are being conducted in collaboration with the Transitional Justice Commission, the Commission for Missing Persons, and the International Foundation for Missing Persons.

Kamal warned that the dangers are not at an end after the fall of the Assad regime. “A violation remains a violation regardless of the perpetrator, and those responsible must be brought to justice,” said Kamal, emphasizing that human rights organizations bear the moral and humanitarian responsibility to monitor and document violations.

Data from Synergy shows that almost 150,000 people in Ras al-Ain have been displaced. Fewer than fifty elderly Kurds remain, along with a handful of Syriacs, one Armenian, and eight Yazidis. 52 villages have been emptied of their original inhabitants, and 8,300 homes and private properties and 100,000 hectares of agricultural land have been seized from the two cities by factions of the Syrian National Army linked to Turkey.

In the cities of Ras al-Ain and Tell Abyad, according to this data, about 85 percent of the population of the two cities, both Arabs and Kurds, have been displaced. The Turkish-backed factions brought more than 5,000 families from other areas to Ras al-Ain. Meanwhile, 60 to 70% of the population resides outside the city, living in camps in Hasakah. Arrests on charges of collaborating with the Autonomous Administration or the Syrian Democratic Forces persist until today.

Synergy documented 890 cases of arrest, including 92 women and 56 children, and 346 people who had been forcibly disappeared.

Synergy documented 890 cases of arrest, including 92 women and 56 children, and 346 people who had been forcibly disappeared. 766 cases of torture and seven deaths under torture were further recorded. At the same time, 121 detainees were transferred to Turkish territory, and 62 of them were sentenced to prison for 13 years to life. Synergy also recorded 70 civilian deaths, including eight women and an infant, 12 field executions, 81 bombings, and 74 incidents of internal fighting between Turkey-backed factions.

Over the past four years, Synergy has submitted more than 100 human rights reports and 35 complaints to international and UN bodies, supported by a database containing more than 35,000 data points, to demand accountability, redress, and compensation.

In conversation with the Amargi, Julia Kurdo, a displaced person from Tell Abyad, voiced their primary demand of the official recognition of Turkey’s occupation of territory in Northeastern Syria and its role in displacing more than 95% of the city’s population, which brought about significant demographic change.

According to Sheikho, Afrin’s displaced population stood at approximately 325,000 people before the fall of the Assad regime, and the remaining Kurdish population in Afrin was less than 25% of its pre-war number

According to Kurdo, Tell Abyad, once known for its cultural diversity with 30% Kurds, 3% Armenians, and the rest Arabs, shows a different story today.. Less than 1% of the original Kurdish population remains, while Arabs from other areas have taken over.

Ibrahim Sheikho, director of the Human Rights Organization in Afrin, told the Amargi that the fourth annual forum organized by Synergy focused on the return of displaced people to Ras al-Ain, Tell Abyad, and Afrin. “The forum served as a platform for communicating the suffering of displaced and refugee communities to local, regional, and international decision-makers,” Sheikho remarked.

According to Sheikho, Afrin’s displaced population stood at approximately 325,000 people before the fall of the Assad regime, and the remaining Kurdish population in Afrin was less than 25% of its pre-war number. After the fall of the Assad regime, 60 to 65% of Afrin’s population, who were internally displaced people, returned. Around 700 civilian deaths have been recorded since the occupation of the city in the war. 3,000 are still missing, a third of them are women. Meanwhile, armed groups, backed by the Turkish state, have seized approximately 5,000 homes and 600 shops, without any official documentation being done to record this due to security concerns.

“The return rate may exceed 60%, but it is not considered safe,” Sheikho warned, stressing that a comprehensive return entails security and legal guarantees, accountability for those responsible for the displacement, and compensation for those affected.

Sheikho outlined that Afrin’s displaced people are currently distributed among several forced displacement sites. In Tabqa, about 12,500 people reside in camps and schools; in Raqqa, approximately 10,000 people reside in schools; in Hasakah, nearly 6,500 people reside in schools; and in Qamishli, approximately 7,000 people reside in schools. In Aleppo, their number has reached around 100,000, with women and children constituting the most significant proportion.

For his part, Ciwan Isso, a lawyer specializing in displaced persons and refugees’ affairs, asserted that the UN’s standards for safe return presuppose that it be voluntary, secure, and dignified, with legal guarantees. According to these standards, returnees must receive effective protection, basic services, adequate livelihoods, respect for civil and political rights, the return of property, and the participation of displaced persons in planning and decision-making.

Isso stressed the critical role expected from the international community, particularly the European Union, in supporting victims and missing persons, providing technical and financial support, enforcing legal accountability, and building independent judicial institutions to guarantee fair trials. He concluded that the Syrian interim government has yet to provide concrete, practical steps to address the issues of victims and displaced persons.

“The interventions of regional powers, particularly Turkey, complicate the process and limit the effective implementation of the legal and constitutional standards required to guarantee victims’ rights,” he added.

Abbas Abbas

Abbas Abbas is a journalist and photojournalist for The Amargi in Qamishli, northeastern Syria (Rojava). He has worked with Al-Youm TV and Ornina Media, and contributed reports and visual stories to local and international outlets, focusing on field coverage and the humanitarian realities of the region.