One year under trusteeship in Êlih (Batman)

In the 31 March 2024 local elections, the Democratic Equality and Freedom Party (DEM Party) won the municipality of Êlih (Batman) with 64.52 percent of the vote. This was the highest vote share among the 30 metropolitan cities in Turkey that held elections in 2024. Êlih, a city that had experienced three trustee appointments since 2016, sent a clear message through this result: “We want to govern ourselves.”

However, this lasted only seven months. On the morning of November 4, 2024, the Ministry of Interior removed Co-Mayor Gülistan Sönük from office on charges of “membership in an armed terror organization” and appointed a new trustee to the Êlih Municipality.

Sönük, describing the process, said: “We received our certificate of election on April 4, and it was dismissed on November 4. The justification cited a prison sentence of six years and three months, and two ongoing investigations against me. But for a year, I have not even been called to testify. All the reasons were political.”

Three periods of the trustee policy

The roots of the trustee practice go back to the early years of the Republic, to the General Inspectorates — special administrative zones established in Kurdish cities. However, trusteeships were systematized under Decree Law No. 674 issued in 2016. This decree, justified under the pretext of “combating terrorism,” paved the way for the removal of elected mayors and their replacement with trustees.

Since 2016, more than a hundred municipalities have been placed under trusteeships in three separate periods. The first trusteeship period began with the above-mentioned Decree Law and continued until the 2019 local elections.Then after the 2019 elections, 48 of the 65 municipalities won by the People’s Democratic Party were seized within a short time.

The third period of trusteeship, which began after the 2024 elections, saw the number of municipalities under trusteeships rapidly increase. In June, Colemêrg (Hakkâri) was placed under trusteeship, followed by Mêrdîn (Mardin), Êlih, and Xelfetî (Halfeti) in November; soon after, the municipalities of Dersim and Wan were also taken over. This time, the practice did not target only the DEM Party but also municipalities governed by the Republican People’s Party (CHP). Trustees were also appointed to Istanbul’s Esenyurt and Şişli districts. For the first time, the trustee regime went beyond Kurdish provinces and turned into a mechanism for targeting all opposition parties.

The Council of Europe deemed these practices “in violation of the European Charter of Local Self-Government” and issued a warning to Turkey.

Too male, too indebted, too damaged

“We encountered a rigid hierarchy, a male-dominated structure, and carrying a debt exceeding 3 billion, 54 million Turkish lira.”

Sönük describes the condition of the municipality they inherited: “We encountered a rigid hierarchy, a male-dominated structure, and carrying a debt exceeding 3 billion, 54 million Turkish lira. More than 900 million of that money had been spent during the pre-election period.”

Within the municipality’s staff structure, appointments were made not based on merit but according to proximity to the Justice and Development Party (AKP). A governance mentality that excluded women became dominant. A male director was appointed to the Women’s Policies Department, and instead of policies promoting women’s freedom, activities reinforcing traditional gender roles, such as “sewing and cooking courses”, were carried out.

Sönük explained further that, “When you visited the women’s department, you were met with brochures that sanctified marriage and made women feel bound to it. There was a mentality that forced women into silence within the family. People who did not speak Kurdish were assigned to public relations. The public was unable to access services.”

Rebuilding the bond with the people

According to Sönük, the greatest damage caused by the trustee administration was the rupture between the municipality and the people. “The trustee had broken the trust between the people and the municipality. Our first task was to repair that connection. As soon as we took office, we organized neighborhood meetings and directly listened to the needs of women, youth, and impoverished districts.”

During this period, several social projects were launched, including daycare centers providing education in the mother tongue, sign language courses, public cafeterias, gluten-free cafés, and free public transportation. Women’s employment was increased, and affirmative action policies were implemented.

“Roads, asphalt, sidewalks — these are the ordinary parts of municipal work,” said Sönük, “What we really wanted was to touch the lives of women and the poor.”

Exposing the trustee’s debts

One of their first actions after taking office was to make the financial situation of the trustee period public: “Seventy-five million Turkish lira had been paid in interest on a sixty-million loan. Every month, we were paying 30 to 40 million liras just to cover the trustee’s debts. We could not obtain new loans, and tax debts that had gone uncollected for three years suddenly began to be deducted once we came into office.”

The municipality began sharing its income and expenditure reports with the press regularly.

The return of the trustee: purges, sales, and profit

Following the appointment of a trustee on November 4, 2024, the municipality once again fell under the control of the governor’s office. In the first weeks, the trustee began a wave of layoffs, dismissing five workers initially, and later purging nearly 120 employees.

According to Sönük, the job descriptions of sociologists and psychologists were changed to “cleaning staff,” while mobbing and forced relocations targeting women employees increased.

The sale of municipal properties accelerated. An employee, on condition of anonymity, stated that a plot of land that had been annulled by court order had been resold months later at the same price. According to the same source, the trustee even dismissed some of the staff he had appointed himself, citing bribery as the motive.

The municipality’s debt rose to 7 billion Turkish lira, yet water and infrastructure problems remained unresolved. Sönük explains: “With just a few drops of rain, Êlih turns into a lake. Despite having no real need, they built a waste transfer station near a residential area, putting the public at risk of disease. Recently, they carried out a massacre of trees along Diyarbakır Street. There was no need to widen that road, but someone stood to profit.”

Meanwhile, the trustee administration launched a transformation of public spaces. When local artists and Kurdish theatre groups applied to perform, their requests were rejected on the grounds that “the program was not suitable.”

Sönük describes this entire picture as “not a politics of service, but a politics of punishment.”

Days of resistance

After the appointment of the trustee, Êlih became the scene of days-long protests. Despite police interventions, tear gas, and pressurized water, the people refused to leave the front of the municipal building. Many were dragged on the ground and beaten. Around 300 people were detained, and more than 40 were arrested.

Today, the municipal building is surrounded by police barricades, and identity checks are carried out at the entrances. Citizens who wish to submit petitions are often stopped by police barriers.

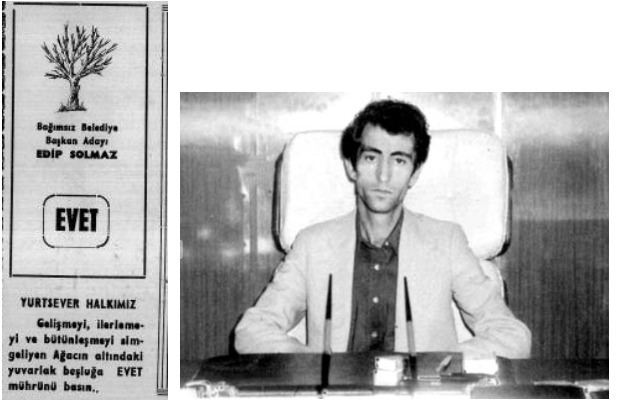

The roots of people’s municipalism: Edip Solmaz

In Êlih, the tradition of people-oriented municipalism did not begin today; rather, it traces back 45 years to the legacy of Edip Solmaz. Elected mayor in 1979 at just 27 years old, Solmaz became one of the pioneers of Kurdish local self-governance, with an uncompromising stance against black-market profiteering and a governance deeply intertwined with the people. He served only 28 days; on November 12, 1979, he was assassinated.

Today, his name remains a reference point on the streets of Êlih. Sönük says they continue this tradition: “Our understanding of municipalism is built through the participation of the people, the labor of women, and the contribution of every segment of society.”

Local democracy and peace

According to Sönük, the situation in Êlih is a summary of the democracy crisis in Turkey: “The trustee policy aims to corrode society. It seeks to suppress the struggle of women, the resistance of the poor, and the people’s right to speak. We know that the trustee is temporary and the will of the people is permanent.”

“On the one hand, the state speaks of peace, and on the other hand, it removes the representatives chosen by the people from office.”

Sönük emphasizes that the solution lies in local democracy: “On the one hand, the state speaks of peace, and on the other hand, it removes the representatives chosen by the people from office. Peace cannot be established with this contradiction. If Turkey truly wants to democratize, the powers of local administrations must be expanded and the reservations regarding the European Charter of Local Self-Government must be lifted.”

Rengin Azizoğlu

Rengin Azizoğlu is journalist and news editor based in Istanbul.