Syria-SDF Integration Deal: From Paper to Practice—The Long Road Ahead

The flag of the DAANES Internal Security Forces, Asayish, flies in Qamishli | Picture Credits: Rojava Information Centre (RIC)

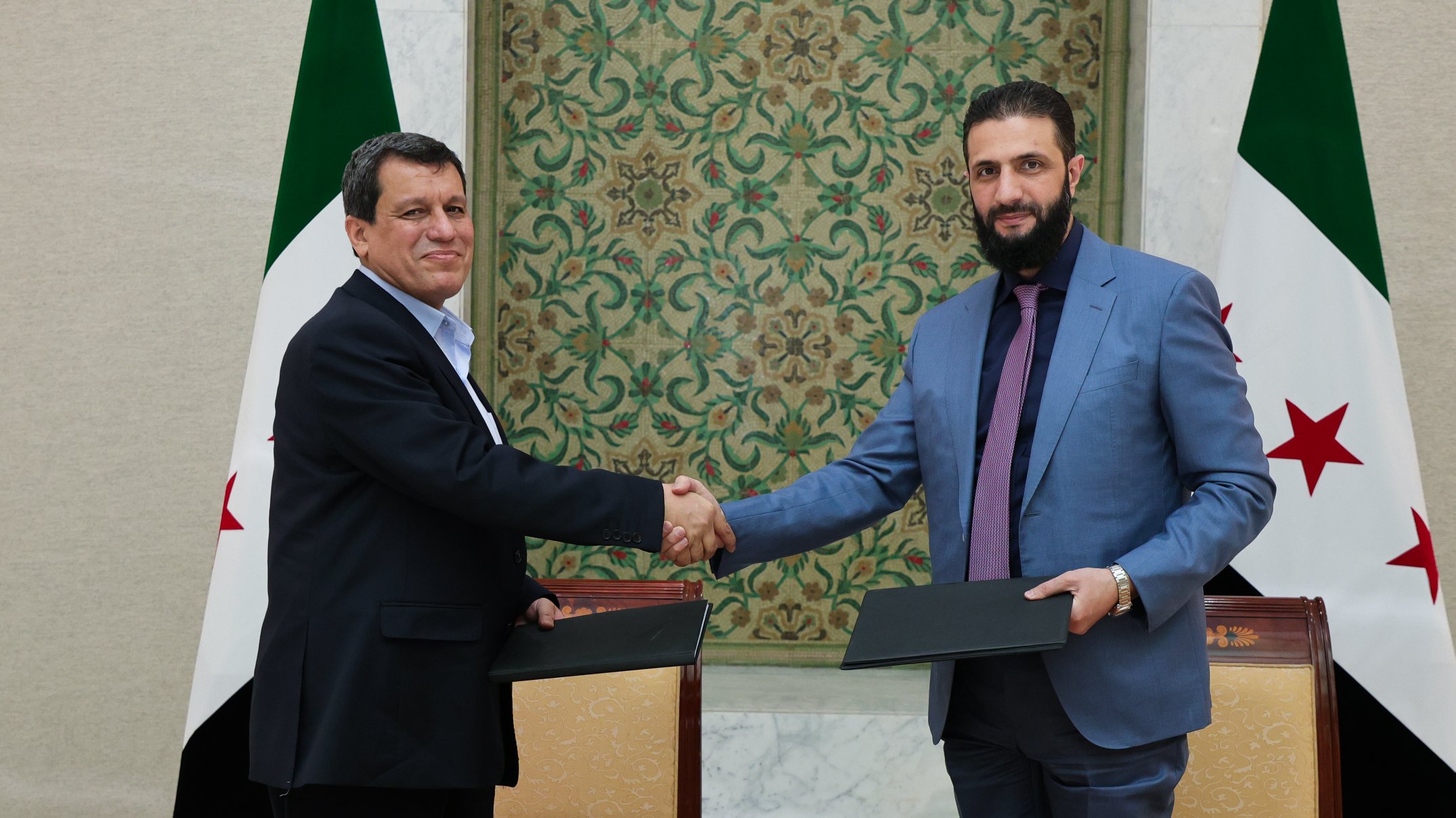

A new integration agreement between the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the Government of Syria was announced yesterday. It is the latest iteration in a string of deals stipulating military, security, and administrative integration, and expresses both sides’ commitment to building a unified Syria and ensuring a lasting ceasefire. The hard work of turning lines on paper into tangible changes on the ground now lies ahead. Debates over the mechanisms for implementing the deal and negotiations over its details are likely to raise challenges, with differing interpretations of its articles already evident.

The agreement is not totally novel, explained the Syrian Minister of Information, Hamza al-Mustafa: “It represents the practical framework for the implementation of the agreements of March 10th last year and January 18th.” Yet some are sceptical about the prospect of the promised “permanent and comprehensive ceasefire on all fronts” being delivered. Particularly in the eyes of Syria’s Kurds, the jury is still out on whether Ahmed al-Sharaa is genuine in his wish to peacefully integrate the Kurdish regions.

Disengagement and military integration

As per the agreement, all military forces will be banned from entering cities and towns, “especially in Kurdish areas”.

Speaking at an online press conference yesterday, Ilham Ahmed – a veteran Kurdish politician and the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (DAANES) Foreign Relations co-chair – emphasised preventing further bloodshed as the key outcome of the deal. As an initial step, both sides are expected to withdraw their military forces to agreed-upon barracks to avoid fresh clashes. The SDF – including the YPJ – will then be structured into three brigades in Jazira under the Syrian Ministry of Defence’s Heseke province military division, and one brigade in Kobane affiliated with Damascus’ Aleppo province. Yet the military integration of fighters will still be done on an individual basis, insisted al-Mustafa.

While a hard end date was not specified by the SDF, the Syrian Foreign Ministry told al-Arabiya TV that “extensive steps of the SDF integration process” should be implemented within one month. As per the agreement, all military forces will be banned from entering cities and towns, “especially in Kurdish areas”.

“Symbolic entry” of Damascus police into Kurdish cities

The agreement stipulates the entry of a small number of Syrian state security personnel into Hasakah and Qamishlo. Fowza Youssef, a senior Kurdish politician and member of the NES committee that had been negotiating with Damascus last year, was unequivocal that this is about coordinating the integration of internal security, rather than establishing any permanent presence. Yet al-Mustafa took a more ambiguous tone, writing that state security forces would enter “to reinforce stability and begin the process of integrating security forces”, without specifying a timescale or any potential exit. Those currently employed by the DAANES as internal security forces will have their positions formalised within the Syrian state system. The same will apply to those working in regional civilian and administrative bodies.

For example, the NES’s oil fields will be run by the Ministry of Energy, but existing civilian employees should continue in their roles and become official state employees. Damascus’ Civil Aviation Authority, meanwhile, will manage Qamishlo Airport. Syria’s Minister of Economy and Industry, Nidal al-Shaar, vaunted the widespread economic opportunities that the integration of the Jazira region into the central state would bring. All border gates will also come under central oversight.

The devil is in the details for the integration of civil bodies

“The Syrian government shall take over all civil institutions in Hasakah province,” reads the agreement. Yet Fowza Youssef asserted that this did not mean complete centralised control, saying “we are determined that our cities should make their own decisions. Local decisions will be made locally.” Hamza al-Mustafa, meanwhile, suggested that local specificities in Kurdish areas would be accounted for, but did not elaborate. He emphasised that “discussion regarding the administrative model has not yet been decided”. Among the potential sticking points is the unification of the legal systems. The DAANES did largely retain Syrian state law as a reference for its courts, yet enacted changes where the law was deemed sexist, adding new articles to ensure women’s rights. Many are now questioning if these provisions will still be upheld.

The agreement includes the official recognition of all school and university certificates issued by NES’s educational institutions. “Certificates from our universities and schools should now be approved by the Interim Government,” said Semira Hajj Ali, co-chair of the DAANES’ Education Board. “We want Kurdish children to be educated in their mother tongue. While the government offers only two hours a week of Kurdish as an elective, the Autonomous Administration will negotiate for Kurdish to be the primary language of instruction. We’ve fought for years to get Kurdish into schools and universities—this can’t be reduced to just an elective.”

Meanwhile, all local, cultural, and civil society organisations – plus media institutions – will be licensed “in accordance with the regulations of the relevant ministries”. This begs questions as to what those regulations will be. During the past 15 years of de facto autonomy in NES, numerous women’s institutions and organisations have been built. Local activists have asserted that they will continue their work, yet there have been worries regarding how Damascus might seek to constrain women’s basic rights and position in society. “The institutions our people gained during the revolution will not be changed”, SDF Commander-in-Chief Mazloum Abdi told Ronahi TV. Yet will institutions such as Mala Jin be permitted to continue their work?

Kurdish rights and the return of displaced people

Ahmed revealed that both Ankara and Damascus claim Turkish forces no longer have a presence in Afrin, which should make it safer for locals to return.

One key demand from Syria’s Kurds has been the constitutional guarantee of Kurdish rights. Unconvinced by verbal promises and worried that al-Sharaa’s recent decree – which declared Newroz a national holiday and permitted a couple of hours of Kurdish lessons in school each week – can be as easily repealed as it was enacted, the region’s representatives have pushed for changes to Syria’s constitution. The cross-party Kurdish delegation established last year to negotiate with Damascus on these matters will continue its work, said Ahmed.

Finally, the agreement specifies the return of all IDPs to their hometowns, with Afrin, Sere Kaniye, and Sheikh Masqoud specifically noted. Returning residents should be able to participate in the local administration of these areas at the governance level. Ahmed revealed that both Ankara and Damascus claim Turkish forces no longer have a presence in Afrin, which should make it safer for locals to return. In Sere Kaniye, too, Turkey is expected to move out imminently.

“Peace isn’t easy”

International commendation for the agreement was widespread, with Iraqi Kurdish leader Bafel Talabani – who was reportedly influential in securing the agreement – saying he hoped “this will mark the beginning of securing the rights of all peoples and communities, especially the Kurds”. Canada’s Syrian envoy, Gregory Galligan, noted “as with all such deals, success will depend on fair and credible implementation to deliver stability for all Syrians.”

The agreement itself remains mere ink on paper, and NES’s political and military leadership has made it clear that the region is not yet in the clear. “We can’t think everything is fine because we have an agreement now,” said Ahmed. “Mistakes may be made, and there is a possibility that things will break down. Hence, we ask the international community to support this deal and act as guarantor powers.” Mazloum Abdi specified that France has committed to taking up such a role.

“I want a ceasefire; I want a deal; I want dialogue. But people are upset. Families are grieving.”

“The agreement is a good thing”, says Shirazad Alo, an Afrin native who has been displaced three times in the past 8 years. “The problem is that there is no trust in them [the Syrian government]. There are still thousands of bodies of Kurdish fighters and civilians who were slaughtered by them. Threatening rhetoric against the Kurds continues. People here are very afraid.” Yet despite this, many see the prospect of determining their future through dialogue as the least worst option. “What should we say?” asks Viyan Ismail, a young Kurdish woman in Qamishlo, “I want a ceasefire; I want a deal; I want dialogue. But people are upset. Families are grieving. I think this deal will work out, but peace isn’t easy.”

Eve Morris-Gray

Eve Morris-Gray is a freelance writer focussed on civil society movements and democracy.