“Yarmouk Is the Cemetery for ISIS”: Inside the Camp That Survived the Caliphate and Fears Its Return

Residents of Yarmouk remember the roundabout as the heart of ISIS terror, where executions were carried out and the heads of victims were placed in a chilling circle for all to see | Picture Credits: Katrine Houmøller

ISIS began encircling the Yarmouk refugee camp, located on the southern edge of Damascus, in 2015. By early 2016, the group had forced its way inside and seized control of nearly half of the camp. What followed, residents say, was one of the darkest chapters in Yarmouk’s long history of war and displacement.

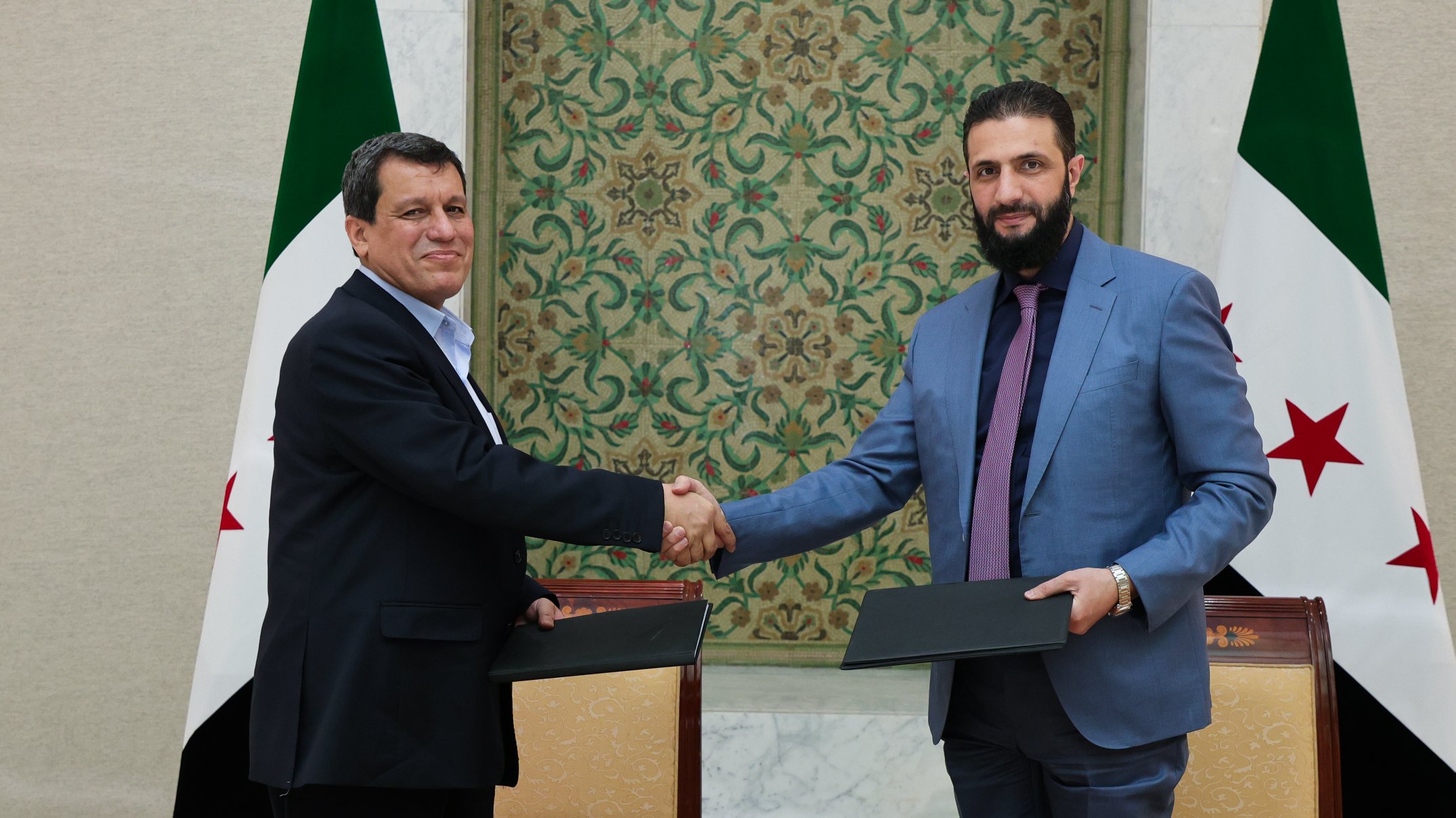

Several Yarmouk residents who had previously joined Jabhat al-Nusra helped ISIS enter the camp, and once ISIS gained a foothold, they officially switched allegiances. The people of Yarmouk suddenly found themselves facing people they had known all their lives. Imad al-Natour, 36, who at the time fought alongside the Free Syrian Army and now serves as Yarmouk’s deputy commander under Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, recalls the shock of confronting his own neighbours in combat, who had become an ISIS fighter.

For civilians, life under ISIS rule was governed by terror and absolute control. “Life was scary,” says Ali Hala, who lived inside an ISIS-controlled area in Yarmouk. He and other residents describe a regime of public punishments involving hands being cut off for theft, incarceration for smoking cigarettes, and executions carried out in the open. Bodies were left in the streets as warnings. Heads were severed and placed on rocks, sometimes arranged in circles around a small roundabout in the camp. Several witnesses claim that ISIS displayed decapitated heads to intimidate the population. Even children were not spared. Residents say ISIS fighters forced them to watch executions.

Ali Hala recalls men being killed with knives, accused of collaborating with the Assad regime or violating ISIS rules. His wife, Suaad Mshilah, describes the suffocating control of everyday life. Anyone entering ISIS areas, to buy fruit or visit family, had to leave their identity card at checkpoints. Men were often barred altogether, suspected of being government spies. Women living under ISIS control were confined to their homes and punished if they appeared in public.

“For ISIS, if they decide a Muslim does not truly believe in God, they kill him and say it is halal. For us [HTS], we would not kill Muslims.”

“The fear never left,” Suaad Mshilah says. “Even now, I imagine them suddenly walking again in the streets between the houses.”

If ISIS were to return, the family would flee immediately. “But to where?” Ali Hala asks. “There is nowhere left to run.”

Ideology of Death

Local leaders in Yarmouk make a clear ideological distinction between ISIS and their own group, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham. “For ISIS, if they decide a Muslim does not truly believe in God, they kill him and say it is halal,” says deputy commander Imad al-Natour. “For us [HTS], we would not kill Muslims.”

Another commander, Ghiyas Tamimei, 33, describes ISIS as having adopted the most extreme and violent interpretation of Islam, weaponising faith to justify murder. “They take the hardest version of religion and use it to kill. They are terrorists. Criminals. There is so much blood on their hands,” he says.

Both leaders agree that ISIS targeted civilians first, soldiers second, using fear as a strategic tool. A strategy, they say, that the current Syrian authorities do not use.

Despite ideological differences, al-Natour acknowledges that militarily, ISIS and HTS are organised in similar ways. “They act like regular armies. The training is the same. Both are strong fighters,” he says.

Unlike during its period of territorial control, ISIS now operates through clandestine networks. According to Tamimei, “ISIS sleepers” remain active: they hide, wait, strike suddenly, and then blend back into the community. He notes that the attacks residents see most often are carried out either by ISIS or by forces affiliated with the Assad regime.

The HTS and local authorities also reportedly closely monitor their own fighters, immediately excluding anyone suspected of previous ISIS affiliation. Intelligence is gathered through surveillance, social networks, and everyday conversations. “From the way someone speaks, what he believes, who he meets, you can sometimes tell if they have an ISIS mindset,” Tamimei says. He adds that civilians often act as the first line of defence, sharing information about ISIS with the authorities.

“The Cemetery for ISIS”

Al-Natour asserts that ISIS no longer holds significant power, and anyone identified is immediately arrested. “Yarmouk is the cemetery for ISIS. If they come back, they will be killed,” he says.

Yet while local commanders express confidence, the situation across Syria suggests the group is far from gone.

He also insists that ISIS no longer operates openly in Syria. He claims that there are no visible ISIS attacks in the cities, and the group does not exist in a way “everyone can see.” If ISIS cells remain, he says, they are hiding in remote desert areas and mountainous regions, not in urban centres.

Yet while local commanders express confidence, the situation across Syria suggests the group is far from gone. ISIS was territorially defeated in Syria and Iraq in 2019 by the US-led coalition and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Since then, around 12,000 ISIS fighters have been held in prisons across north-eastern Syria, with tens of thousands of their relatives detained in camps such as al-Hol. Despite these measures, the group’s legacy of violence and terror remains. Human rights organisations, including the United Nations, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch, have documented widespread and systematic abuses by ISIS, from mass executions and sexual slavery to torture and the recruitment of children.

In recent months, the fragile system containing ISIS detainees has begun to show cracks. Syrian government forces have advanced into areas previously controlled by the SDF, including around al-Hol camp and key detention facilities near Raqqa and Hasakah. SDF spokesperson Farhad Shami warned that up to 1,500 ISIS members may have escaped during the clashes, though the figure could not be independently verified.

The SDF has repeatedly raised alarms about deteriorating security in prisons and camps holding former ISIS fighters. Officials say they requested international intervention to secure the sites, but no action was taken.

At the same time, the United States has begun transferring ISIS detainees out of Syria. US Central Command confirmed that around 150 fighters have already been moved from Hasakah province to Iraq, with up to 7,000 more potentially to follow. CENTCOM said the transfers aim to prevent mass prison breaks and the regrouping of militants.

For the people of Yarmouk, the threat is written into their streets, their ruins, and their memories.

For residents, commanders, and analysts, the threat of ISIS in Syria is quite vivid. Although the group no longer controls territory as it once did, fragile detention systems, contested frontlines, and shifting international attention leave the door open for it to regroup and strike again.

For the people of Yarmouk, the threat is written into their streets, their ruins, and their memories.

Suaad Mshilah, who lives in Yarmouk, still has nightmares of the checkpoints, the black flags, the heads on stones. “We know what they are capable of,” she says. “Even when everything is quiet, you feel they could come back at any moment.”

Al-Natour recounts that ISIS once ruled the camp through fear and extreme violence. He stresses that while the group thrived on chaos, injustice, and despair, the people of Yarmouk will not be intimidated again.

Katrine Houmøller

Katrine Dige Houmøller is a Danish freelance journalist based in Beirut, Lebanon, specializing in coverage of the Middle East with a focus on war, crises, and human rights. She was nominated for the Danish Kravling Prize for her reporting from Syria following Bashar al-Assad’s fall in 2024, and in 2025 she received the DMJX award for her project on child soldiers in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon.