Syria’s Six Remaining Jews Celebrate Hanukkah in Damascus

This article is co-authored by Massa Bashour and Majed Badawi

In December 2025, Syria’s Jews gathered to celebrate their first Hanukkah in the Syrian capital after decades of persecution by the Assad regime. Syrian Jewish cultural activist Joseph Jajati is now cautiously optimistic about the Jewish community becoming part of Syrian life again, despite security concerns that remain.

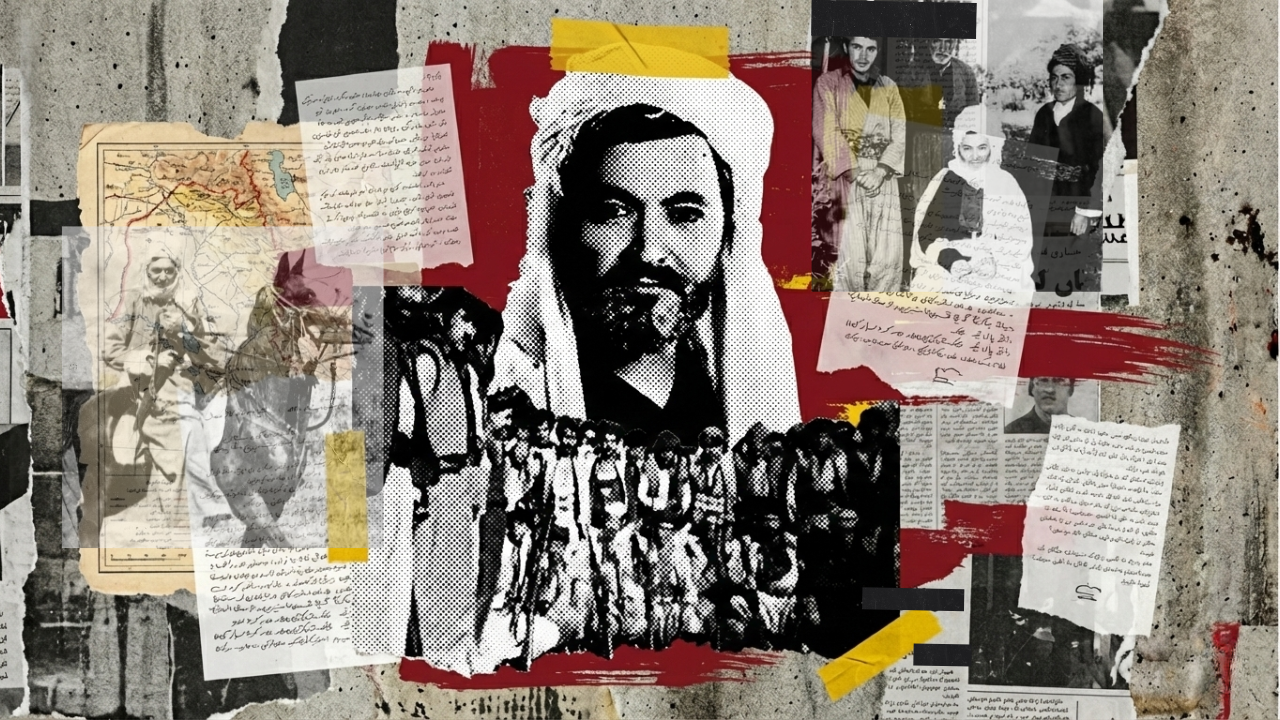

For more than 2,000 years, Jews were part of Syria’s social, religious, and cultural landscape. From the narrow streets of Damascus to the once-busy Jewish quarter of Aleppo, their presence in the land preceded all modern political and religious strife.

Today, that historic community has been reduced to just six individuals, all living quietly in Damascus. But, over the past year, rare developments have signaled a re-engagement with this nearly vanished past, and after decades of erasure, and following the fall of the Assad regime, Syria’s Jewish community is becoming more visible.

Jewish life in Syria dates to before the birth of Christ. It continued under Roman, Byzantine, Islamic, and Ottoman rule, with Damascus, Aleppo, and Qamishli emerging as important centers of Jewish life. These cities’ synagogues, scholars, and merchants played significant roles in regional trade and intellectual exchange.

By the early 20th century, Syria’s Jewish population numbered in the tens of thousands, but that number declined sharply after the establishment of Israel in 1948. Regional conflict, movement restrictions, property confiscations, and periodic violence pushed many Jews to leave. By the 1990s, most of those who remained were permitted to emigrate, settling primarily in the United States, Israel, and Europe

Syrian Jewish activist Joseph Jajati was born to one of the families who left late in the 20th century, leaving Syria when he was two years old in the late 1990s to move to the United States. Jajati rejected the idea that Syrian Jews left out of ideological commitment. He said families often fled quietly, without informing relatives, fearing reprisals if their departure became known.

He said the initiative is explicitly national rather than sectarian, emphasizing that Jewish presence in Syria long predated modern political divisions: “We were here long before Assad and long before Israel.”

He is now the founder of the Syrian Mosaic Foundation, a civil initiative aimed at bringing Syrians of different faiths together around a shared national identity. The project emphasizes coexistence, cultural heritage, and the rejection of religious stereotyping. As he described it, his relationship with Syria was shaped less by politics and more by his personal history: “All I knew was that I was born in Syria. And I felt I had to see it.”

He said the initiative is explicitly national rather than sectarian, emphasizing that Jewish presence in Syria long predated modern political divisions: “We were here long before Assad and long before Israel.”

Living Under Watch

Under the Assad regime, Syria’s remaining Jews lived under strict restrictions that reached deep into daily life. Travel between provinces, or even cities, required prior security approval from intelligence services. Getting clearance to travel was uncertain, monitoring was constant, and fear shaped routine decisions.

The restrictions were especially visible in Damascus’s Jewish Quarter, which was effectively sealed off. “There was a security officer stationed in front of every synagogue in the quarter, despite the fact that they were closed,” recalled Bekhour Chamntoub, one of the few remaining Jewish residents and the head of the Jewish community in Damascus.

“Another officer was always posted at the entrance to the Jewish Quarter itself,” Chamntoub said, adding that the officer questioned and harassed all who entered the area, “even people who regularly came to my well-known tailoring shop”, making daily errands more of a chore than it already was.

Religious life was likewise constrained. While Judaism was not officially banned, Syria’s jews avoided public or even semi-public observance. Families marked holidays quietly, if at all; deliberately keeping rituals out of sight to avoid attracting attention or provoking security concerns.

That reality has shifted under Syria’s new authorities, according to Chamntoub, and Syrian Jews are now better able to travel in their country.

The change is perhaps most evident in religious expression, as he said they can now openly speak about and celebrate our holidays: In 2024, Chamntoub hosted a Jewish journalist, Itai Anghel, in his home in Syria, and together they lit the Hanukkah menorah, something that he said would have been unthinkable only a few years earlier.

For Syria’s dwindling Jewish community, these changes do not erase decades of fear or isolation. But they mark a clear break from a period in which even the most private expressions of identity were shaped by caution, silence, and surveillance.

Reconnecting with a Lost Past

Earlier in 2025, Jajati helped organize several delegations of rabbis and religious figures to Damascus, meeting with government officials from the foreign ministry, the ministries of economy and social affairs, and university representatives in Damascus University.

Later, in December 2025, Syrian authorities granted an official operating license to a Jewish-Syrian foundation. It was the first formally recognized Jewish organization in modern Syrian history.

That same month, two rabbis made a rare, tightly coordinated visit to Aleppo, entering synagogues that had been closed for decades. The visit drew international attention as a symbolic reconnection with a city once central to Syrian Jewish life.

Candles Without a Quorum

Despite early optimism, security for Jewish life in Syria remains fragile. During Hanukkah in 2025, some of the remaining Jews lit candles in private. With fewer than ten Jews in the country, it was impossible to form a minyan, the quorum required for communal prayer. Observance took place individually, as quiet expressions of continuity rather than public celebration.

He said the initiative is explicitly national rather than sectarian, emphasizing that Jewish presence in Syria long predated modern political divisions: “We were here long before Assad and long before Israel.”

But positives are still there: “Before, it wasn’t even possible to say you were Jewish,” Jajati said. “Something changed.”

For members of the Syrian Jewish diaspora, even small details have taken on new significance. Jajati mentioned a moment during a recent visit to Damascus that struck him as transformative: “When I arrived in Damascus during Hanukkah, the hotel we stayed in offered a menu that included kosher food suitable for Jewish holiday rituals.” Though a small detail, Jajati sees it as a first step “toward becoming one shared fabric again, as we once were.”

Syrians Before Sects

Initiatives like the Syrian Mosaic Foundation, which aim to foster dialogue and highlight shared heritage, face significant challenges. Sustaining programs is difficult amid economic hardship and limited resources, while social tensions and lingering mistrust complicate engagement.

Jajati also reflected on the more personal dimension of this work, stating that the multiple sides of the Syrian population remain critical of him and see him as an outsider. But he argued that this has less to do with his Jewish heritage and more to do with the difficulties Syrians have endured over five decades of dictatorship: “We are facing problems as Syrians, not as Jews.”

Despite divisions, he insisted that Syrians share more than they are often willing to admit: “Our shared culture is bigger than our differences.” Jajati stressed that accountability must be both legal and moral, calling on the government to enforce stronger laws aimed at curbing hate speech, which has remained a major problem in post-Assad Syria, leading to violence and massacres against ethnic and religious minorities, rather than policing opinions.

The story of Syria’s Jews today is not one of mass return or full revival. It is a story of recognition and cautious reopening

He concluded with a challenge directed at both society and the state: “Did we really attain freedom? Are we willing to recognize the problems? And are we actually working on them?”

The story of Syria’s Jews today is not one of mass return or full revival. It is a story of recognition and cautious reopening. While many Syrian Jews abroad have expressed interest in visiting, permanent return remains unlikely. Jajati said current conditions make resettlement difficult, particularly for those who have already built lives elsewhere. When asked about his own position regarding returning, Jajati was blunt: “If I didn’t feel welcomed and at home, why would I come back?”

Massa Bashour is a scenographer and freelance journalist based in Damascus, Syria, holding a double major in painting from Damascus University and scenography from the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts.

Majed Badawi is a scenographer and a freelance fixer, news video, and photo editor based in Damascus, Syria. He holds a major in scenography from the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts.

The Amargi

Amargi Columnist