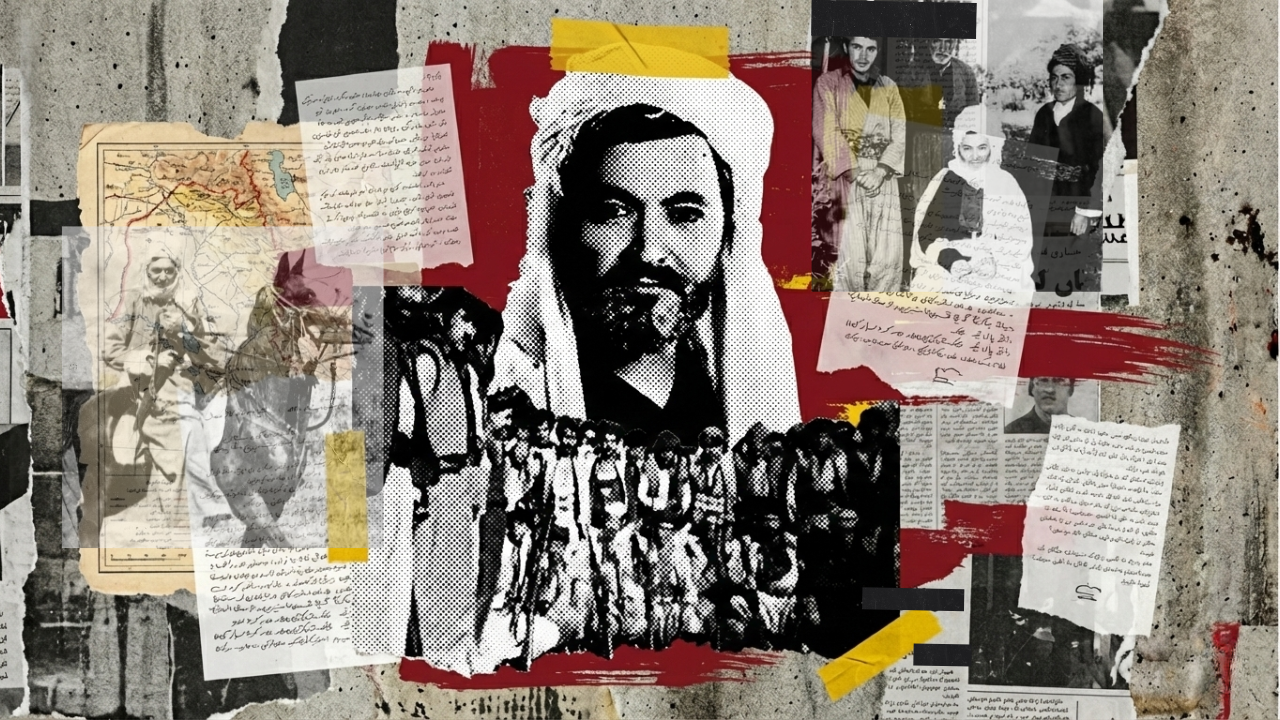

Yarmouk’s Night Guards: “I’m Fighting for My Religion, Not for the People or the Country.”

In a shadowy corner, two men hide as the soldiers approach. They tense for a bust, but when nothing is found, they are quietly let go | Picture Credits: Saleh al Saleh

It is 11 p.m. and Yarmouk, in southern Damascus, is dark and deserted. The loud morning life in the streets where children play, shopkeepers shout, and men converse over tea is gone. The place is empty.

Local Deputy Commander Imad al-Natour, 36, drives through the ruins of Camp Yarmouk slowly. Rain splashes against the windshield, blurring his view. He wipes the glass with his hand to clear the mist.

Al-Natour’s phone never leaves his hand. A walkie-talkie sits in his pocket, a pistol in his waistband. He is always in contact with his men on night patrol, ready if needed. But for now, he looks like any other civilian: jeans, jacket, and a backwards baseball cap.

“I don’t depend on the authority’s work. I work for God, not for the money,” he says.

He stops at one of the few kiosks still open to buy tobacco, water, and the spices he has promised his wife. The shopkeeper chats casually, unaware of the patrols in the surrounding streets.

A few hours later, back in the car, Imad al-Natour says, “I’m different when I’m working. I turn into someone else, acting according to Islamic rules. When I’m home, I’m just a civilian. It’s like living separate lives.”

Through checkpoints and nightly patrols, the new Syrian authority presents itself as a source of security – a claim many residents quietly question.

Just ahead is a white Nissan pickup truck with five men clad in all-black. They wear heavy ammo belts across their chests and carry AK-47s over their shoulders. A couple show their faces underneath black beanies, others cover them with black masks.

These men are in Imad al-Natour’s unit. He steps out of his car, gives some brief instructions, then returns to the driver’s seat to accompany them around the war-torn camp.

Through checkpoints and nightly patrols, the new Syrian authority presents itself as a source of security – a claim many residents quietly question.

Nights with Yarmouk’s Patrols

Imad al-Natour tailgates the white pickup as it loops through the same streets again and again, scanning for what he calls “unusual movement.” He explains that the patrol stops civilians, checks whether people are safe, and stands ready to intervene if anything escalates.

According to the local authorities, drugs are the biggest problem in Yarmouk, followed by theft. What they encounter most often is hashish (hash), Captagon, and other illegal pills. They claim most of the drugs come from Lebanon, but crystal meth is trafficked from Iran. The patrols mostly catch users, not dealers.

Weapons are another challenge. So far, the authorities have confiscated only around ten percent of the weapons in the area. They take away the guns, but the men carrying them are usually not arrested, even though civilian possession is illegal.

Near a dark corner in a narrow street, al-Natour’s unit asks a taxi driver to pull over. The soldiers jump out of the pickup and approach the vehicle; they search the car and check the driver’s license.

“Of course, we check whether the car belongs to him,” Imad al-Natour says, watching his men work. “If it’s not his, then it means he’s stealing other people’s money.”

After confirming the car’s ownership, they let the taxi drive off into the night.

The patrol slips back into its rhythm. Every third or fourth street corner, someone notices movement. Sometimes it is nothing. Sometimes the soldiers search young men they cross on the street and question people about why they are out so late. Sometimes they stop civilian cars and open their trunks. At some point, one of them shouts at a man and orders him to remove the scarf covering his face. “It’s illegal to wear a mask. Take it off,” the soldier yells, and the patrol continues.

At 12:30 a.m., Imad al-Natour heads home. His men remain on the streets, maintaining control of Yarmouk until the next morning.

“Worse Than We Feared”

For many, the authorities’ presence is more than a temporary shadow on the streets. It reaches into homes, disputes, and everyday life.

One of the Yarmouk’s local authorities’ recent arrests is a 50-year-old man who asks to remain anonymous, fearing repercussions.

He was arrested after a dispute with his neighbor, when, in the heat of the moment, he insulted her and said something sacrilegious. She reported him to the local police, and he was detained for two days – not for the insult, but for offending God.

In the detention facility, he quickly learned how the system worked. Here, treatment could be negotiated: he says they moved him to a single cell after he offered cash and cigarettes. He also claims officials pressured him to pay 600,000 Syrian pounds, around $50, to secure his release.

He still has the signed police document detailing the blasphemy charge – a reason for arrest that matches other civilians’ accounts. Though his claims about paying money could not be independently verified.

Religious instructions appear everywhere, posted on walls and scrawled in graffiti: “You must pray”, “Alcohol is forbidden”, “Women must wear the hijab”.

“Things have changed,” he says. “You can now speak openly about politics. But when it comes to Islam, they are extremely strict.” He adds that under Bashar al-Assad, insulting the president could lead to terrible consequences, but insulting God did not provoke a reaction. Now it is the opposite.

Several residents of Yarmouk describe the authority’s vehicles patrolling the streets with loudspeakers blaring “Allahu Akbar!” nonstop. Religious instructions appear everywhere, posted on walls and scrawled in graffiti: “You must pray”, “Alcohol is forbidden”, “Women must wear the hijab”.

“We were supposed to be free after the new regime came,” Anonymous 50-year-old man says, but as he describes fighters stopping people in the streets, enforcing tight control, he concludes things are worse than before, as they have lost even basic personal freedoms.

He believes Ahmed al-Sharaa’s rule is only temporary, and in his view, when elections come, the best outcome would be a secular leader.

Private Power, Public Fear

Residents across Damascus and Yarmouk describe the same pattern: authority is fragmented, and each group operates according to its own beliefs and rules.

For Anonymous 50-year-old man, the problem is not Ahmed al-Sharaa and how he governs the country from above. It is what happens below. Everything depends on who controls your street, your neighborhood, your camp – and how strict the local commander is where you live.

A civilian from Damascus, speaking anonymously, says members of the new security forces act based on personal beliefs, rather than overarching laws that apply to everyone.”

. They carry out what he calls “private favors”, which include intervening in arrests or arranging releases for personal reasons.

A 22-year-old woman in Yarmouk puts it more bluntly: “They don’t have a legal system. They have the mentality of Islamists.”

“I’m fighting for my religion, not for the people or for the country,” says Imad al-Natour.

When speaking with Yarmouk’s leaders and soldiers, many start their conversations the same way, and a familiar line repeatedly comes up: “I’m talking to you as a civilian.” Yet the power they wield is very far from being civilian. They are armed and organized and shape daily life in Yarmouk; they decide who is stopped, who is punished, and who is left in peace.

“I’m fighting for my religion, not for the people or for the country,” says Imad al-Natour. He shrugs and leans back, “We freed them. But now they ask: What did you actually do? People are never satisfied.” He sees his side as different from the Assad Regime, which “cheated people and stole their money.” He believes they brought freedom.

Inside commanders’ houses, conversations are calm, almost casual. Outside, Yarmouk sleeps under the watchful eyes of men who move between the roles of neighbor, enforcer, and soldier. In this oxymoronic place, freedom and fear coexist, and order and oppression often overlap.

Katrine Houmøller

Katrine Dige Houmøller is a Danish freelance journalist based in Beirut, Lebanon, specializing in coverage of the Middle East with a focus on war, crises, and human rights. She was nominated for the Danish Kravling Prize for her reporting from Syria following Bashar al-Assad’s fall in 2024, and in 2025 she received the DMJX award for her project on child soldiers in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon.