Turkey’s deposed mayors and the Council of Europe

Screenshot

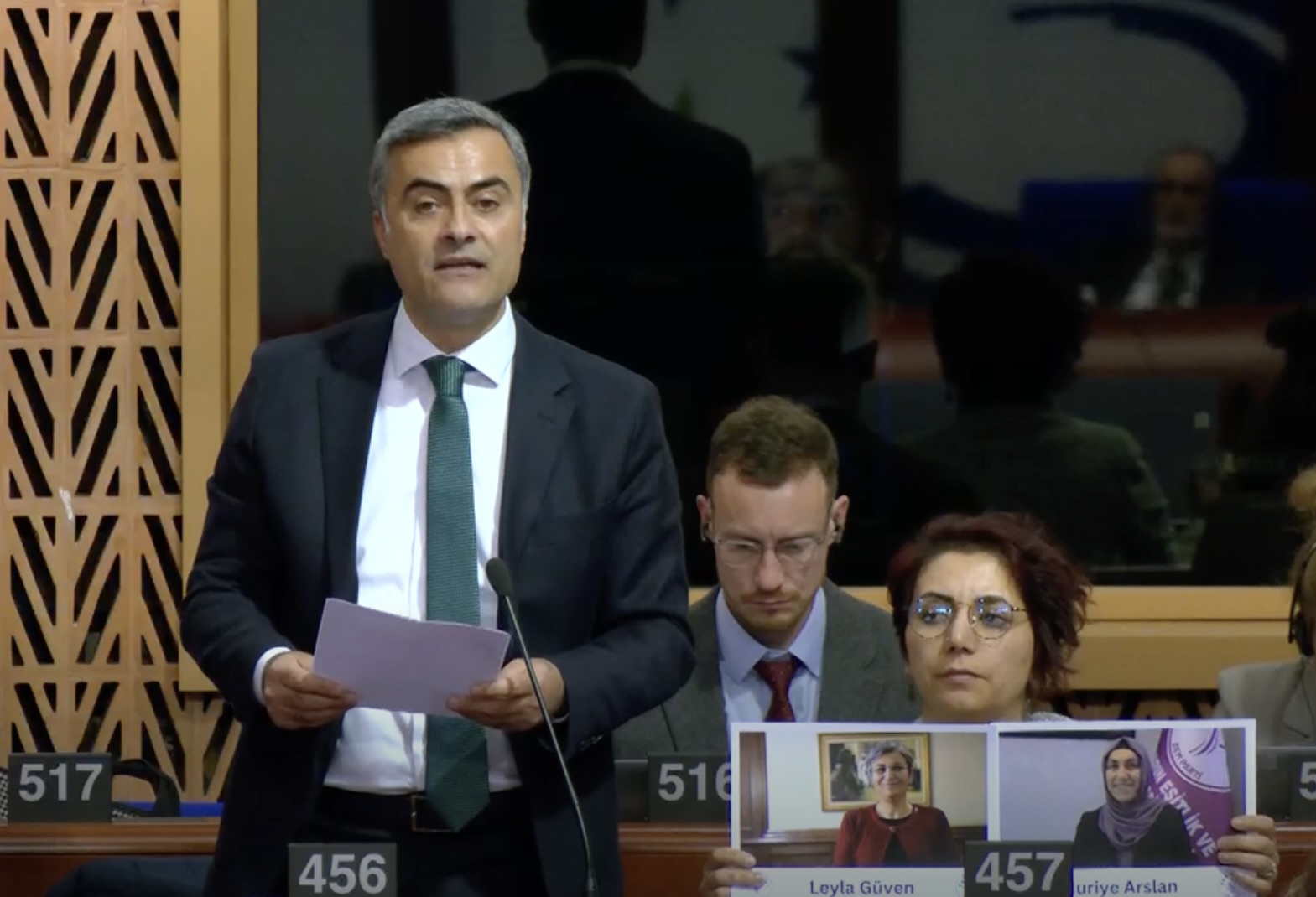

Abdullah Zeydan, the deposed DEM Party co-mayor of the metropolitan city of Van, was in Strasbourg last week at the Council of Europe. The Council’s raison d’être is the preservation of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law. Debates at the Congress of Regional and Local Authorities – which Zeydan was there to attend – focused on freedom of assembly and freedom of speech in parliamentary assemblies. So, what is the Congress doing for deposed and imprisoned mayors, and what more could they be doing?

Years of judicial attack

The Turkish state has long used its judicial system to pursue Kurdish politicians.

In 2016, they began deposing Kurdish mayors en masse using trumped-up charges of ‘terrorist’ links. Local power was wrested from elected mayors and councils and handed to government-appointed regional governors. These unelected “trustees” used their immense personal power for self-aggrandisement, leaving cities impoverished and often heavily indebted. Of the 102 Kurdish mayors elected in 2014, 97 were deposed and replaced by “trustees”. Of the 65 elected in 2018, six were decreed ineligible, and a further 48 were replaced.

Van has been under trustee control for most of the last nine years. The mayor elected in 2014 has been in prison since 2016. The mayor elected in 2019 is in exile in Germany, escaping a potential 30-year prison sentence. When Zeydan was elected with 55% of the vote in 2024, the authorities claimed he wasn’t eligible to run and recognised the runner-up candidate from the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) instead, whose vote share was a meager 27%. Mass protests within Turkey and abroad persuaded them to respect the decision of the voters at that time. But less than a year later, they suspended Zeydan on the basis of a case that the European Court of Human Rights ruled illegitimate, and appointed a trustee in charge yet again. Zeydan has been given a three-year and nine-month prison sentence, and his appeal waits at the High Court. Last week was the first time he had been allowed to travel to take up his delegate place at the Congress.

The CHP in the spotlight

The ostensible excuses given against the CHP are predominantly accusations of corruption, but the real motivation remains political

Several Kurdish mayors elected in 2024 have now been deposed, but in recent months, the government’s focus has shifted from the DEM Party mayors to those from the main opposition, the Republican People’s Party (CHP). The ostensible excuses given against the CHP are predominantly accusations of corruption, but the real motivation remains political. The most prominent of the imprisoned mayors, Ekrem Imamoğlu, is not only the mayor of Istanbul, but also Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s main rival for the presidency.

The arrest of the CHP mayors is a powerful example of historic truth expressed in Martin Niemöller’s prose poem. First, they came for the Kurds, and the CHP not only did not speak out – they voted for the illegal legislation that made possible the trustee system and the mass arrests of MPs. More recently, as with the attempted disqualification and subsequent dismissal of Zeydan, they have shown support for Kurdish politicians under judicial attack, but the pattern of political arrests had already been set and was allowed to become normalised.

Despite this background and the CHP’s central role in the century-long persecution of Turkey’s large Kurdish minority, the DEM Party has taken a principled stand, supporting the deposed and arrested CHP mayors and protesting every clampdown on democracy and freedom of expression.

The CHP includes a broad range of political opinion, from social democrats to hardened Turkish nationalists, and even at the Congress in Strasbourg – as at the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly – it was clear that not everyone is comfortable linking the government’s attacks on their own party with the government’s attacks on the DEM Party. From some CHP politicians’ speeches, one would never guess that these anti-democratic practices had been going on long before the CHP became the target.

Turkey’s mayors at the Congress

Last week was far from the first time that Turkey’s systematic destruction of local democracy had been discussed in the Congress of Regional and Local Authorities. In the previous session in March, the situation of the mayors was the subject of an emergency debate that discussed the removal of Zeydan as well as the imprisonment of Imamoğlu, which had occurred just eight days before. Introducing that debate, David Eray, one of the rapporteurs on Turkey appointed by the Congress, explained that they had thought their discussions with the Turkish government following their monitoring report were going well and that they had drawn up a roadmap for Turkish democracy. But Turkey had failed to respond.

Despite their debates and diplomacy, Turkey has found the Congress relatively easy to ignore.

Since that session, the rapporteurs have returned to Turkey and met with some of the imprisoned mayors. They also found themselves having to visit a Turkish youth delegate to the Congress who had been arrested on his return to Turkey on the basis of his speech there. Enes Hocaoğulları had criticised his government for police violence and democratic backsliding, and is accused of “publicly disseminating misleading information” and “inciting hatred and enmity”. He was held for a month in pretrial detention before being released at a hearing attended by many foreign political representatives, but he will still face trial in February. This arrest was clearly very provocative. While it was prompted by Turkish social media, it could also be seen as an indicator of the degree of impunity Turkey is allowed.

Despite their debates and diplomacy, Turkey has found the Congress relatively easy to ignore. Along with the Council of Europe in general, and the Committee of Ministers in particular, which is charged with following up on the rulings of the European Court of Human Rights, the Congress could do much more.

Their excessive caution was demonstrated at the time of Turkey’s last local elections in 2024, when the DEM Party took care to deliver a detailed dossier to the Congress listing all the addresses where they had uncovered anomalies in the voting registers, which showed large numbers of new names listed at single apartments in key constituencies. The Congress’s election monitoring team, rather than investigate the evidence they had been given, chose places to visit at random, and what appears to have been a carefully planned attempt to manipulate the results did not appear in their report.

The Priorities of Congress

It is also clear that the Congress, like its member states, prioritises some international problems above others. At the top of the list is Ukraine, for which Russia was expelled from the Council of Europe, and which the Secretary General of the Council of Europe describes as “our topmost priority”.

Palestine is the issue about which most European politicians would prefer not to talk. It was notable that in the debate on Freedom of Assembly, the only person to mention the problems faced by pro-Palestine demonstrators – other than the United Nations rapporteur who led the debate – was a representative of the AKP. Turkey likes to pose as the Palestinians’ defender, though demonstrations that criticise the Turkish government’s hypocrisy in continuing trade with Israel are quickly cracked down upon.

Turkey’s continued “democratic backsliding” cannot be ignored, as it is a member state of the Council. However, as a member state and a state of strategic importance, it is given considerable leeway.

Last week, photographs of imprisoned mayors from Ukraine were shown on the big screen in the debating chamber. When deputies from Turkey’s opposition Parties tried to hold up photographs of their imprisoned mayors, they were informed that pictures were not allowed.

While no one wants Turkey to be expelled like Russia, there are possibilities for sanctioning their role within the Council of Europe.

Normalisation and the sidelining of democracy

Fayik Yagaizay, the permanent representative of the DEM Party to the European Institutions in Strasbourg, recalls that when Leyla Guven was imprisoned in 2009, while a member of the Congress, the rapporteurs visited her twice in Diyarbakir prison. Her situation was the first item on every Congress agenda and was prominently featured on the Congress website. Embarrassed Turkish congress delegates wished for her release, which came 4 ½ years later. However, with Turkey’s mass arrests of DEM Party mayors, the situation became normalised and lost its prominent billing.

If the Congress were to repeat this level of attention by similar or new means, that would, of course, be welcome; however, its impact would be weakened by an international climate that pays decreasing attention to democratic values and by the loss of credibility of European countries whose own governments have been increasingly shown to be hypocritical and inconsistent.

While one of the rapporteurs was discussing what more could be done to draw attention to the arrests of the mayors and to put pressure on Turkey, the leader of her party, UK Prime Minister Kier Starmer, who is already under fire for his active support of Israel, was congratulating himself on agreeing to the sale of warplanes worth billions of pounds to Turkey.

Sarah Glynn

Sarah Glynn is a writer and political activist based in Strasbourg. She has previously worked as a university lecturer in Scotland and as an architect, and has published books and articles on immigrant political mobilisation, identity politics, Islamism, low-cost housing, unemployment, and ecosocialism. Her writing on Kurdish issues has included a regular column for Medya News and articles for Green Left and Bella Caledonia. www.sarahglynn.net