Limits of Solidarity: Rojava, Kurds, and Kurdistan

Solidarity, in its dominant Middle Eastern usage, has rarely achieved its stated ideal purpose: uniting the colonized, suppressed, and exploited across borders and identities. Instead, solidarity has often been weaponized as an ideological apparatus – one that consolidates Arab, Turkish, Persian nationalisms, and Islamist supra-nationalism, while disciplining stateless peoples into silence.

For Kurds, therefore, solidarity has repeatedly meant a demand to abandon an anti-colonial struggle and join the geopolitical ambitions of those who have colonized Kurdistan for a century.

The concept of solidarity, as mobilized by regional states and by intellectual elites, has done something quieter, more structural, and more violent. It has reproduced a hierarchy of suffering in which the Kurdish struggle is, at best, an inconvenience and, at worst, a betrayal; a hierarchy where Kurds are repeatedly asked to demonstrate loyalty to their colonizers; a hierarchy where Kurdish demands for self-determination are framed as “foreign plots”, while the colonial foundations of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria remain unspeakable.

For Kurds, therefore, solidarity has repeatedly meant a demand to abandon an anti-colonial struggle and join the geopolitical ambitions of those who have colonized Kurdistan for a century. The result is not only political hypocrisy; it is an epistemic regime that normalizes Kurdish disposability. That disposability is now being operationalized again in Rojava, Western Kurdistan, where the Syrian Arab Republic calls for jihad against Kurds, and Kurds face yet another massacre.

Solidarity as a Demand for Kurdish Self-Erasure

One should begin with the uncomfortable fact that the Middle East’s most vocal “solidarity” states are also, structurally, the region’s colonial powers over Kurdistan: Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. Yet Kurds are routinely asked – morally and politically – to be the loudest bodies in the streets for Palestine, to demonstrate Islamic unity, to chant the slogans of Arab nationalism, and to subordinate Kurdish aspirations to “the central cause”.

This is not solidarity. It is the demand that the colonized prove their worthiness to the colonizer’s moral universe.

The regional states publicly posture against Israel while maintaining forms of cooperation, trade, and security alignment, sometimes overt, often covert, yet they redirect the anger of their populations toward internal enemies. In Turkey, the Palestinian question has long been instrumentalized as domestic political theater: a language of moral righteousness used to consolidate state legitimacy while intensifying the repression of Kurds and Kurdish political movements. The message is implicit but clear: you may be Kurdish, but to be legitimate, you must perform as a loyal subject of the Turkish-Islamic nation; your Kurdishness must not produce political demands. This is why Kurds can be praised as “brothers” in Gaza protests while being targeted as “terrorists” the next morning.

Even more pernicious is the accusation repeated by states and echoed by intellectuals that Kurds are “proxies of Israel and America.” The claim functions less as an empirical statement than as a disciplinary myth: it delegitimizes Kurdish autonomy by marking it as foreign contamination. But this accusation survives precisely because it does not need any evidence; it rather needs only a regional common sense in which Kurdish agency is unthinkable unless sponsored by an empire. Under this logic, Kurds are never political subjects; they are instruments. This belief about Kurds works largely because each of the four states’ central governments have been dehumanizing Kurds for a century; and a dehumanized object cannot possess the agency of a human subject.

Campus Solidarity and the Coloniality of Knowledge

When Kurds insist on speaking, when we ask what solidarity means if it excludes the colonization of Kurdistan, the room often shifts.

The problem is not only state hypocrisy. It is also the region’s knowledge-production machinery – the ways the “Middle East” is narrated, taught, and theorized, even in supposedly critical spaces.

After October 7, many universities in the US organized panels, seminar series, and teach-ins framed around Palestine. These spaces often performed a radical critique of Western imperialism and Zionism, while simultaneously reproducing a regional colonial denial: Kurdish history appeared only as an afterthought, if at all. The U.S. intervention in Iraq and Syria was frequently invoked; Saddam Hussein’s Anfal genocide against Kurds was not. Syria’s Ba’athist demographic engineering – such as the Arab Belt project – rarely surfaced as part of the region’s colonial archive, yet the sufferings of Palestinian Arabs dominated the debate.

When Kurds insist on speaking, when we ask what solidarity means if it excludes the colonization of Kurdistan, the room often shifts. The response is not engagement but cold silence, defensive irritation, the subtle insinuation that raising Kurdish oppression is a distraction from “the real issue,” which is Palestine. Silence, here, is a method. It enforces what may be said and what must remain unthinkable.

In one such discussion, when asked why Palestine holds such central importance for the Middle East, an Arab scholar answered: “Palestine is the origin of Arab nationalism.” This statement – perhaps intended as an analysis – unintentionally revealed the problem’s architecture. If Palestine functions as the origin myth of Arab nationalism, then “solidarity with Palestine” is easily transformed into a demand that non-Arab peoples become footnotes to an Arab nationalist story. A Kurdish question becomes illegible not because it lacks ethical weight, but because it threatens the ideological monopoly of Arabness as the region’s political subject.

Kurdish freedom is imagined not as decolonization but as a threat to Arab political cohesion. Kurds are asked to sacrifice their liberation so that others may preserve their hegemony.

When another person asked why Kurds do not receive attention comparable to Palestinians, the answer I witnessed was not only dismissive but overtly racist: “Palestinians are geniuses, they have language, poetry, music,” implying Kurds do not. This is colonial reasoning, the same logic used historically to deny Kurds’ nationhood: your language is not a language; your culture is not culture; therefore, your claims are not political. It is what happens when someone can oppose violence in Gaza while remaining comfortable inside Arab nationalist supremacy. And it is precisely here that “solidarity” reaches its limit: it becomes a moral performance that refuses self-critique.

This refusal is not abstract. It shapes policy. Consider the now-well-known comment attributed to Saeb Erekat, an advisor to Mahmoud Abbas, who reportedly said Kurdish independence would be “a poisoned sword against the Arabs.” Whether one agrees with his strategic calculation or not, the statement reveals the regional logic: Kurdish freedom is imagined not as decolonization but as a threat to Arab political cohesion. Kurds are asked to sacrifice their liberation so that others may preserve their hegemony.

So, what is solidarity in this context?

In its dominant regional usage, solidarity often functions as an instrument of ideological governance. It means: join our cause, but do not name our crimes; chant our slogans, but do not demand reciprocity; be visible for Palestine, but be invisible for Kurdistan.

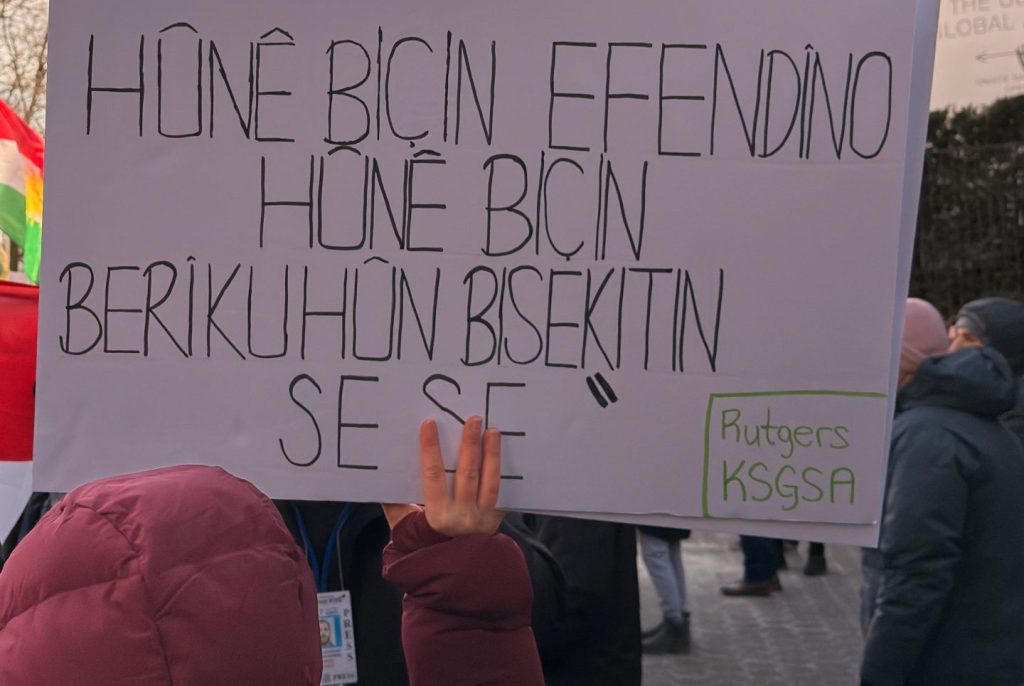

This is why Kurdish participation in Gaza protests is often tolerated only on the condition that Kurdish demands remain unspoken. The moment Kurds say, “We stand with Palestinians – and we also demand recognition of Kurdistan’s colonization; we refuse to be sacrificed,” solidarity turns into accusation. Kurds become traitors. Kurds become “agents.” Kurds become the problem.

But solidarity that requires self-erasure is not solidarity. It is a submission.

Against Kurdish Disposability

If solidarity is to be more than a slogan, it must stop treating Kurds as sacrificeable – sacrificeable for Arab nationalism, sacrificeable for Turkish geopolitics, sacrificeable for Iranian state ideology, sacrificeable for the fantasy of Islamic ummah. It must refuse the colonial common sense that holds some nations in the center and while making others expendable.

A politics that cannot make room for Kurdish freedom is not liberation politics. It is simply the redistribution of power among colonizers.

And in Rojava today, that distinction is not theoretical. It is the difference between survival and annihilation.

Mahsun Oti

Mahsun Oti, a PhD student in Anthropology at Rutgers University in the US.