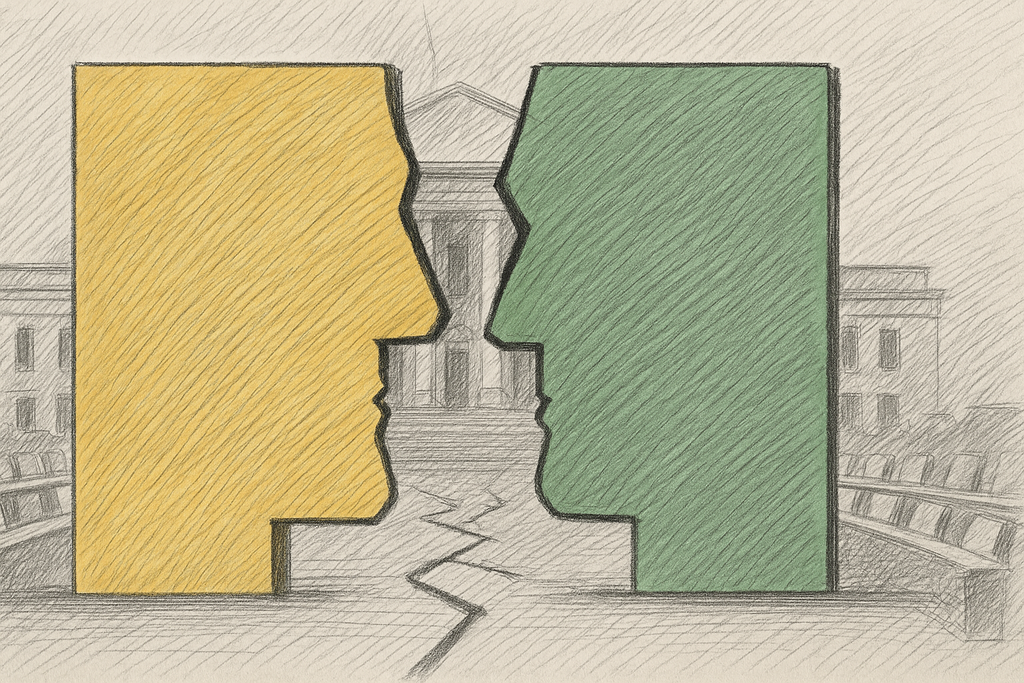

The 50/50 Power-Sharing Pact: Kurdistan’s Ruling Parties at a Standstill

Nearly a year after its delayed parliamentary elections in October 2024, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) still lacks a new cabinet. Coalition talks between the two legacy parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), continued for months, creating a political vacuum and affecting the government, economy, and public trust. Once seen as a success story in Iraq, Kurdistan is now stuck in a political deadlock.

The Renewed Struggle over Governance

Meant to bring clarity, the October 2024 election only deepened the crisis in the Kurdistan Region. The KDP won 39 out of 100 seats; the PUK only 23. The outcome left the KDP unable to govern alone. Ever since, the two parties have been arguing over the meaning of governing together.

For the PUK, the issue is beyond the number of seats—it is about power in the ministries that control the region’s security and finances. In a May 2025 report by Shafaq News, senior PUK figure Burhan Sheikh Raouf emphasized his party’s demand for more than token positions, pushing instead for meaningful authority in the management of sovereign and service-related ministries. This would mean either running the region with two separate administrations or through equal say over areas like oil, security, and foreign relations.

The KDP insists that the results imply that the PUK must take a step back. On May 15, KDP leader Masoud Barzani stated, “I call on the PUK and KDP to form a government based on one region, one parliament, and one government as soon as possible. If there is no agreement on this basis, we will proceed with our work. But a government will not be formed on a 50/50 basis.” Days later, PUK Deputy Prime Minister Qubad Talabani responded at the Delphi Forum in Silêmanî (Sulaymaniyah), with courtesy and annoyance. “I respect Mr. Masoud Barzani, but it’s been a long time since a government was formed in this way. I don’t know why we are still talking about this. I can’t recall the last time a government was formed.” His comments reflect nearly 30 years of rivalry.

Since the 1996 peace agreement that ended the Kurdish civil war, the KDP has largely controlled the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), while the late PUK leader Jalal Talabani spent more time in the central government in Baghdad. In more recent years, internal issues—like the rise of the Gorran Movement, the PUK–Gorran split, and the removal of Lahur Sheikh Jangi from leadership—weakened the PUK.

Today, new PUK leaders appear more united and assertive in demanding genuine partnership in governance. Failing to secure this, they will threaten to default to a two-party administration. This idea resonates because old disputes from the civil war era persist. Both parties still maintain separate peshmerga and asayish (security) forces and hold distinct shares of the economy, separate from the official KRG groups.

A Pact Born from Fear

After the First Gulf War, Kurdish forces established a degree of autonomy from Baghdad in 1991. In May 1992, the first elections in the Kurdistan Region resulted in an even split between the KDP and PUK, marking the beginning of the so-called “50/50” power-sharing system. Every ministry had two heads—if a minister is from the KDP, the deputy would be from the PUK, and vice versa.

According to political scientist Dr. Alan Noory, the arrangement never a democratic compromise, but rather a deal to prevent renewed violence. “The decision to rule 50/50, which pushed all the other parties out of parliament, was accepted on the claim that otherwise another bitter civil war would start,” he told The Amargi. “The irony is that the prevention of civil war only lasted two years.”

Indeed, the unified government soon fell apart. After the U.S.-mediated Washington Agreement in 1998 restored peace, the two parties continued to rule separately: the KDP in Hewlêr (Erbil) and Duhok, the “yellow zone,” the PUK in Silêmanî, the “green zone.”

After Saddam Hussein’s fall, the two parties signed a new unification deal in 2006. The zones merged, and the power-sharing model was revived. For a while, the parties worked together, representing a united Kurdish voice in Baghdad and overseeing a growing oil economy. But over the past decade, this balance eroded.

In 2013, the PUK suffered electoral losses and internal divisions after former PUK leader Nawshirwan Mustafa formed the Gorran Movement. Strengthened, the Barzani-led KDP argued that power must reflect electoral results, not outdated traditions. The PUK, however, insisted on the 50/50 principle.

In Dr. Noory’s view, the focus on vote counts obscures a deeper truth: from the start, the foundations of electoral legitimacy in Kurdistan were weak. He recalls the 1992 election, “From the very first hours, it became clear to many that it was chaos, fraud, and corruption.”

Party Lines in Politics and the Military

The KDP-PUK rivalry extends to the disputed areas—especially Kirkuk. After the December 2023 provincial elections, the PUK nominated Rebwar Taha as governor. In August 2024, he was elected in Baghdad during a session that the KDP did not participate in. President Abdul Latif Rashid quickly approved the outcome. The PUK celebrated a return to power in the province; the KDP rejected the move as illegitimate, accusing the PUK of striking secret deals with pro-Iran Shi’a groups.

This division also runs through the Kurdish military system. While the peshmerga forces are officially under one ministry, in reality, they remain split between the KDP’s Unit 80 and the PUK’s Unit 70. Even joint brigades follow party command structures. The KDP’s ties to Turkey and the PUK’s relations with Iran fuel the mistrust. External alliances also affect the parties’ dealings with Baghdad.

The U.S. and UK have attempted to bridge this intra-Kurdish divide. In 2022, a Pentagon-led reform roadmap aimed to unify the peshmerga and eliminate partisan control—with little effect. Dr. Noory believes that solutions lie beyond slow reforms. To him, the cartel-like functioning of Kurdistan, where land, wealth, and power are divided among entrenched tribal elites, reflects a reality in Iraq as a whole. “Any attempt to define this situation as a democracy is a major failure in analysis.”

The People In-Between

With no new cabinet, the KRG cannot approve a new budget or implement reforms. Civil servants, teachers, nurses, and other workers face salary delays once again. For years, both parties have blamed each other for unpaid wages, electricity shortages, and inflation.

Mohammad, a shopkeeper in Erbil, is concerned about jobs, electricity, and conditions for a decent life. Like many, he is tired of living through crisis after crisis. “We need a government to fix these problems, but the parties are not doing anything,” he told The Amargi. Sima, a university student in Silêmanî, believes that neither party truly serves the people. She expects any future agreement will only benefit elite interests.

Voter turnout in 2024 was reported at about 72%. However, many expressed that they voted out of duty, not a belief in change. Anger over corruption fuelled support for new political movements. The New Generation Movement, led by Shaswar Abdulwahid, came third with 15 seats. Their campaign on ending the KDP-PUK monopoly found support from younger voters. The party claims it will not repeat Gorran’s mistake of joining the government and losing its base.

Democracy as the Path Forward

The power-sharing pact between the two parties was never based on a shared vision for governance. It was a short-term fix for a rivalry. Neither side wanted to be in the opposition, fearing loss of influence. Now, both parties fail to operate within this old framework. A new one has yet to emerge.

A real democracy would be the only other option. That, however, seems to scare both parties. Without agreement on a new system, the situation will cause more trouble—beyond delayed cabinets. But even with this established structure, some still believe in change.

“I am convinced that within those parties, there are people who can find solutions,” says Dr. Alan Noory, urging for strategic engagement with individuals who still act out of a commitment to public welfare.

Rebaz Majeed

Rebaz Majeed is a Kurdish journalist, researcher, and photographer based in Berlin whose work bridges conflict reporting, academic inquiry, and digital fact-checking. He has covered politics, migration, and security in Iraq and the Kurdistan Region for Voice of America, and later worked with Lead Stories as TikTok’s fact-checking partner for the MENA region, specializing in misinformation and digital verification. His research has explored gender, violence, and political dynamics in Iraq. A polyglot journalist, Rebaz holds a BA in International Studies from AUIS and an MA in Interdisciplinary Studies of the Middle East from Freie Universität Berlin.