Voters in Kirkuk face another election shaped by ethnicity not policy

When campaign banners went up across Kirkuk this autumn, they told a familiar story. The Kurds spoke to the Kurds, the Arabs to the Arabs, and the Turkmen to the Turkmen. Each community ran its own candidates, held its own rallies, and promised to defend its own part of the city. In a place once celebrated as Iraq’s mosaic of coexistence, the campaign trail has become a map of division. No party dares to speak for all of Kirkuk. As the province prepares to vote again, it does so not as one city but as three competing worlds, bound uneasily by oil, memory, and mistrust.

The winner of an election rarely governs here alone, and the loser rarely accepts defeat.

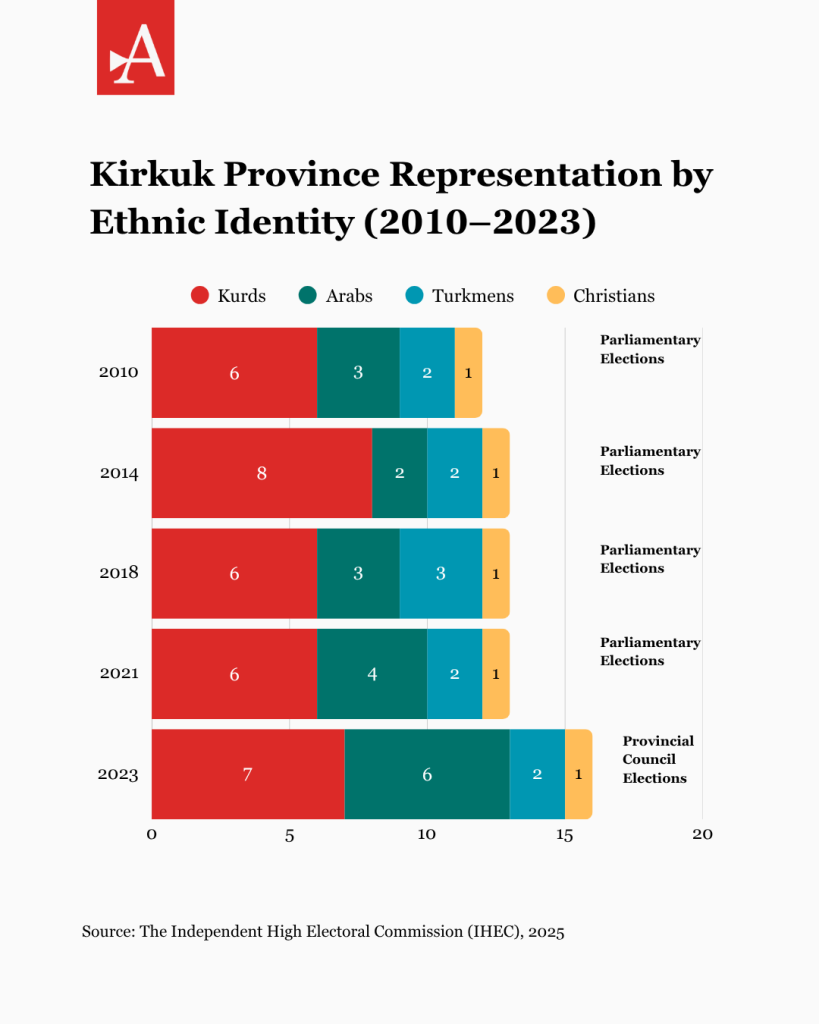

Kirkuk is where Iraq’s deepest issues converge. Home to 1.77 million people and rich in oil, the province is split among the Kurdish, Arab, and Turkmen communities. The winner of an election rarely governs here alone, and the loser rarely accepts defeat. This year’s vote, Iraq’s sixth parliamentary election since 2005, allocates 13 seats to Kirkuk, including one seat in the Christian quota, and three seats reserved for women. Yet the province’s political and economic weight far exceeds its share in the legislature. 251 candidates — 76 of them women —are competing for the votes of 958,141 registered voters, at roughly 74,000 votes per seat.

Every election in Kirkuk revives old disputes over land, power, and belonging. Campaigns that begin with talk of services and jobs quickly turn into contests of identity. “The competition over votes among the various ethnic and political groups has intensified,” says Shwan Dawdi, a political analyst from Kirkuk. “Each community now understands its own electoral capacity and no longer expects support from others.” Consequently, the result is that Kurds mainly compete within themselves for about six seats, Arabs for four, and Turkmen for two.

Dawdi’s assessment is blunt: “There are no clear electoral mandates, only vague and populist promises. People vote along ethnic or tribal lines rather than for certain policies.” In this environment, Kirkuk’s shared life, including its mixed markets, bilingual streets, and shared memories, has become collateral to a politics that rewards division and punishes compromise.

Given the lack of a recent census that identifies ethnicity, elections now act as a proxy for demographic trends.

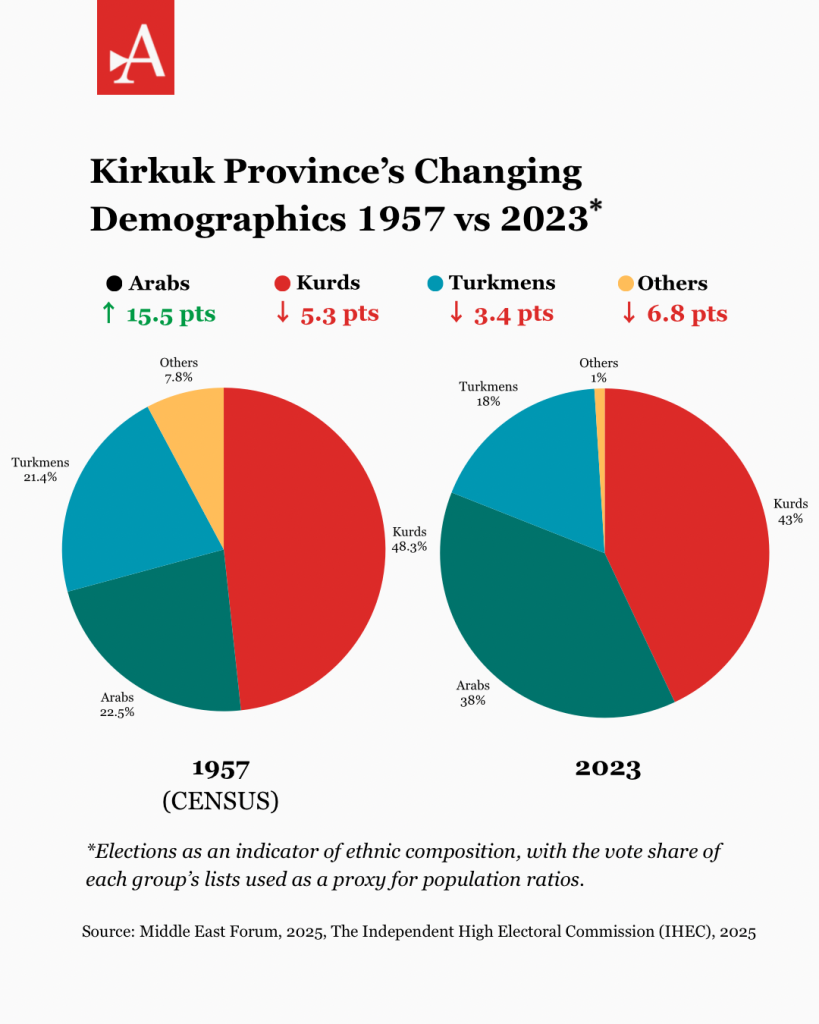

Kirkuk’s demographics help elucidate the tensions. In 1957, Kurds made up 48.3% of the population of Kirkuk province, Arabs 22.5%, Turkmens 21.4% and the rest consisted of Assyrians and other ethnic groups. Decades of Ba’ath-era Arabisation and subsequent political upheavals have since reversed that balance. Given the lack of a recent census that identifies ethnicity, elections now act as a proxy for demographic trends. Kurdish votes fell from 54% in 2014 to 43% in 2023, while Arab support rose from 28% to 38% and Turkmen from 17% to 18%. These shifts indicate how demographic engineering and shifting power patterns since 2017 have transformed Kirkuk’s social and political landscape. The Kirkuk referendum was intended to resolve this issue and determine whether disputed areas, including Kirkuk, Diyala, Salah ad-Din, and Nineveh, would join the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Originally planned for November 2007 but repeatedly postponed, the vote remains unscheduled since Article 140 of Iraq’s constitution requires reversing Saddam-era Arabisation before holding the plebiscite, a process complicated by the return of thousands of displaced Kurds after 2003.

The struggle for power is also tied to oil. Nearly a century after the legendary Baba Gurgur well erupted in 1927, the British oil giant BP has returned to Kirkuk with a multi-billion-dollar deal to increase production, capture gas, and build new power capacity. The agreement is not just about business; rather, it signals Baghdad’s renewed authority over the province after years of tension with Erbil. If Iraq succeeds in boosting national output from 4.4 to 6 million barrels per day by 2029, Kirkuk will once again become central to the country’s political and economic disputes.

“Not only in Kirkuk, but across Kurdistan and Iraq, regional influence and political money shape outcomes. However, they mostly serve political parties, not specific communities.”

Beyond Iraq’s borders, Kirkuk’s politics draw in larger powers. Turkey presents itself as the protector of Iraq’s Turkmen, with several leaders, including Turkish President Erdoğan and ultranationalist party leader Devlet Bahçeli, repeatedly calling Kirkuk a “Turkmen city.” Ankara’s influence extends through oil pipelines and the Ceyhan port, giving it leverage over both Baghdad and Erbil. Iran, meanwhile, views Kirkuk as part of its strategic corridor from Tehran to Syria. By supporting Shia Turkmen groups and other Arab Shia factions, Tehran aims to block Turkish influence and secure its own foothold in northern Iraq. The Kurdish factions are likewise split along regional lines; the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) maintains close ties with Turkey, while Iran backs the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK)’s dominance in Kirkuk.

For Dawdi, the regional influence on election outcomes extends across the country. “Not only in Kirkuk, but across Kurdistan and Iraq, regional influence and political money shape outcomes. However, they mostly serve political parties, not specific communities,” he says. The absence of visionary leadership, the dominance of identity politics, and weak civic engagement have left Kirkuk trapped in cycles of mistrust and competition. “The city mirrors Iraq’s broader fragmentation,” he concludes.

On 11 November, the ballots will be counted and the likely outcome will be familiar: Kurds leading but divided, Arabs strong but fragmented, Turkmen pivotal but split.

There are no easy fixes. Progress depends on cross-ethnic coalitions that focus on what residents actually need: clean water, electricity, security, and jobs. For example, Kirkuk faces persistent electricity shortages and high unemployment. The city receives only about a third of its power requirements, forcing it to rely on private generators, which, in turn, lead to frequent blackouts. Unemployment stands at 15–16%, but rises above 70% in poorer districts like Hawija, leaving many residents trapped between joblessness and unreliable basic services. Solving these issues requires fair power-sharing inside provincial institutions, without turning every decision into a zero-sum contest. None of this will happen naturally; it requires leaders to be willing to spend political capital on cooperation, not division.

On 11 November, the ballots will be counted and the likely outcome will be familiar: Kurds leading but divided, Arabs strong but fragmented, Turkmen pivotal but split. The real question comes after: can Kirkuk’s leaders govern together, or will they once again let identity define the next government term?

This election will not just fill 13 seats. It will test whether Iraq’s centre and periphery can share authority, whether Erbil and Baghdad can find balance, and whether foreign powers can be kept from turning local politics into another battleground. The ballot is only a tool.

Renwar Najm

Renwar Najm is an Iraqi Kurdish journalist with a career that began in the early 2010s at the esteemed Awene newspaper. He holds a master’s degree in Peace and Conflict Studies from the University of Kent and Philipps University of Marburg.